Silence = Death: The beginning of the epidemic

To mark World AIDS Day, Katherine Ott takes us back almost 40 years when people began to sicken and die from a mysterious and frightening disease that became a global pandemic.

ACT UP (gran Fury), SILENCE = DEATH, 1987. Courtesy New Museum, New York, William Olander Memorial Fund

Activists directed much of their rage at the Reagan administration; the president remained largely silent about the epidemic until 1987 when he declared AIDS “public health enemy number one.” The SILENCE=DEATH emblem, adopted that same year by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), was a call to change tactics, since neither silence nor community self-reliance had stopped the deaths. The pink triangle was a symbol of the gay rights movement.

It has been almost 40 years since the first official reports of HIV and AIDS began to alarm the public. It was not called that back then, of course, and all anyone knew is that people—first young gay men, then heterosexual women, injection drug users and then hell broke loose—were sick with diseases that were highly unusual for them. The importance of this history lies both in the sheer notoriety of the virus and in the significant impact the syndrome has had on American science, life, and culture. The global impact is equally immense. AIDS is the most publicized disease of the past half-century and has become a household word, but even today many people lack a historical context for why it is so feared and so devastating.

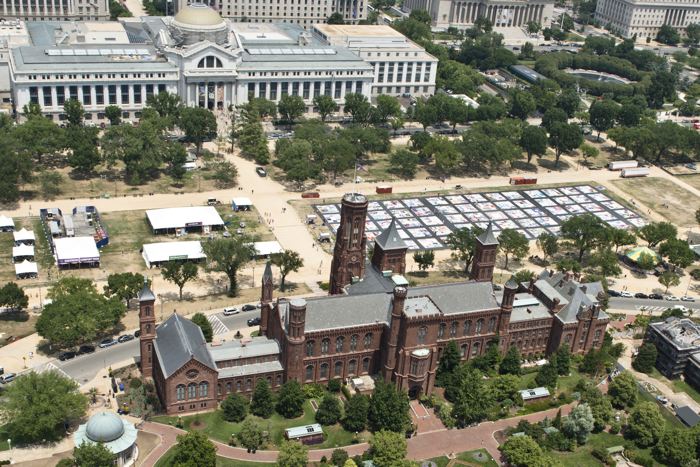

The 2012 Smithsonian Folklife Festival displayed featured part of the AIDS Memorial Quilt on the National Mall. (Photo by Walter Larrimore)

The AIDS Memorial Quilt is an ever-growing symbol of the toll of AIDS. The Quilt consists of thousands of handmade fabric panels made by family or friends of the deceased which memorialize persons who have died of AIDS.

Displayed in Washington, DC in October 1987 for the first time, the quilt had been conceived by Cleve Jones in San Francisco, “. . . what led to the Quilt is that I felt we were failing to reach the vast, overwhelming majority of Americans who do not live on the Coasts and do not know gay people.” By 1996, the AIDS Memorial Quilt had grown to the size of twenty-nine football fields, 45,000 panels.

The history of HIV-AIDS has been told many times, from different perspectives. Analysis is widely available on the internet and in professional journals, books, and newspapers, and don’t forget the health information distributed everywhere from doctor’s offices, schools, grocery stores, and restaurants, to phone booths and gas station bathrooms. Rather than simply replicate what others have done and aware that we can’t tell much of the complicated history in a small space, The American History Museum created an exhibition (now online) that concentrates on the epidemic’s earliest years, 1981-1987.

The Surgeon General’s Report on AIDS, 1982 (courtesy National Museum of American History)

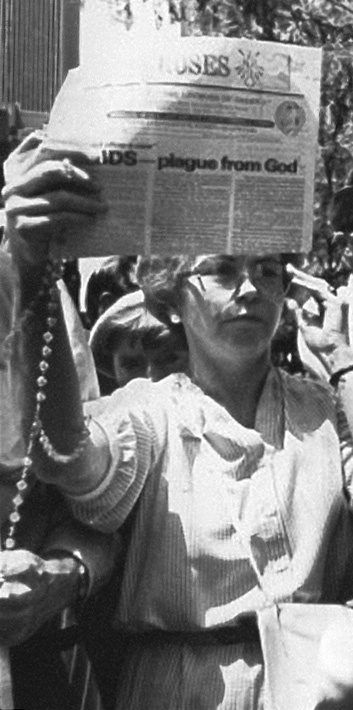

Another reason to focus on the early years is the dramatic difference in tone and urgency when compared with today. My interns and other young people with whom I work approach STIs (sexually transmitted infections) and protection as largely uncontroversial and not very interesting. They have little comprehension of the intensity of the conflict that surrounded public discussion of sex, drugs, condoms, and LGBTQ legitimacy back in the 1980s.

Most states still outlawed same-gender sex in the 1980s. Many Americans, deeply offended by homosexuality, objected to any acceptance of it. Some of them considered it a sin, and believed AIDS was a suitable punishment. (Donna Binder, photographer)

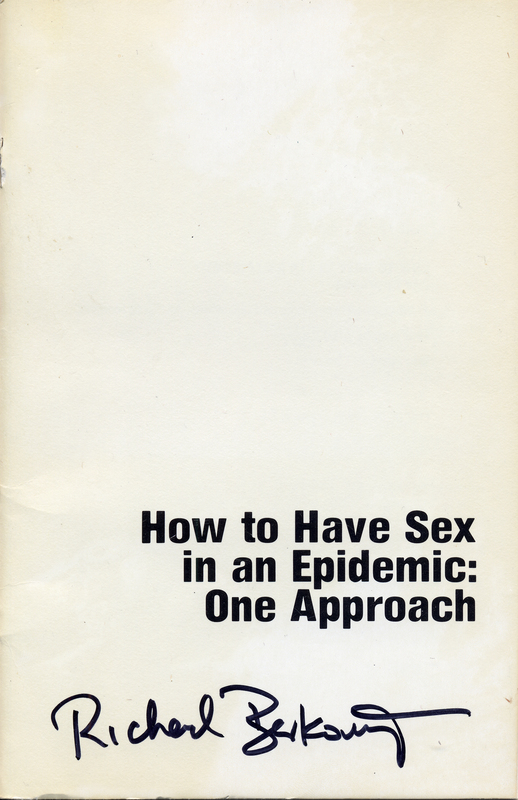

Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz, gay men infected with the virus, wrote this 1983 sex-positive guide.

The museum has a strong collection of objects related to HIV and AIDS. We have been collecting objects and other materials almost from the beginning. The ephemera are especially rich, such as ACT UP posters, demonstration flyers, health information pamphlets, and magazines. We also have lab equipment from Jay Levy’s San Francisco lab (one of the scientists who isolated the virus), various medications, lots of condoms, needle exchange objects, political buttons and T-Shirts, an AIDS Memorial Quilt panel for Roger Lyons, red ribbons, and more.

Visit the online exhibition “HIV and AIDS Thirty Years Ago” for a look at the public health, scientific and political responses in the early phase (1981-87) of the global pandemic, including oral histories and interviews.

Azidothymidine—AZT—brought the first real hope for treatment. It prolonged some patients’ lives by slowing replication of HIV. It was introduced in 1987 under the name Retrovir®.

Listen to our award-winning podcast, Sidedoor: “This color is who I am,” which takes a look at the early HIV/AIDS crisis through the eyes of artist Frank Holliday, whose life and work were changed by it forever.

This is an edited version of a post by Katherine Ott, curator in the Division of Medicine and Science at the National History Museum, that was originally published by the Museum of American History blog, “O Say Can You See?”

Posted: 1 December 2018

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture