Backroom Stories: The graphic (art) tale of the U.S. Exploring Expedition’s report

Joan Boudreau describes how some humble wooden blocks led to the reunion of a collection linked to the U.S. Exploring Expedition—one of the most important sources of scientific knowledge and collections for the young Smithsonian.

In 1995, I was a museum specialist in the American History Museum’s Graphic Arts Collection, a unit that studies the technological history of printing and printmaking. One day that year, Nanci Edwards, a colleague from the museum’s Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, showed me a small box of what looked to be engraved wood blocks. Nanci wasn’t sure what the blocks were and thought our department might more easily identify them.

Engraved wood block for “Patagonians,” printed in Volume 1, page 118 of the Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition Narrative volumes. (Photo courtesy National Museum of American History and Smithsonian Institution Archives,)

The small blocks, most averaging 2 x 2 x 1 inches, appeared to date from the mid-19th century. A few blocks were marked with a date, others with a location, and yet others with hand-written numbers or number stamps. The engraved subject matter included simply made but skilled renditions of landscapes, native peoples, dwellings and artifacts. I was fascinated by the subject matter but was also aware that printing blocks of this period were unusual, if not rare, and were also poorly represented in the collection. So I was quick to agree to research their history and attempt to accept them.

My first task was to investigate the images the blocks would have printed. A large clue me from an exhibition a decade earlier at the Natural History Museum. The 1985 exhibition Magnificent Voyagers discussed the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1838 to 1844, its findings, and its accumulated natural history collections, many of which are still housed across the Smithsonian. Led by Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition investigated and collected specimens from the newly identified continent of Antarctica, islands across the Pacific, Africa, South America, and what became parts of the northwestern United States. A multi-volume expedition report about the exploration was prepared between 1844 and 1872 and published as the Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842, with accompanying scientific volumes.

U.S.S. Vincennes in Disappointment Bay, Antarctica ca. 1840, attributed to Capt. Charles Wilkes (1798-1877).

Once a cursory connection was made between the engraved images and the expedition publication, I requested a Smithsonian Institution Libraries copy of the five Narrative volumes, and access to the other volumes, to help match up all the engraved images. I discovered that the occasional markings on the backs and sides of the blocks, as it turns out, indicated the date of their preparation, the subject of their image, and/or the chapter and page numbers of the printed image in the publication.

Engraved wood block marked “20th Octr/44,” used to print “Street View, Honolulu” in Volume 3, page 415 of the Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition Narrative volumes. (Photo by Joan Boudreau)

Engraved wood block marked “Luzon, Iwaiti Native,” used to print “Native of Luzon” in Volume 5, page 311 of the Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition Narrative volumes. (Photo by Joan Boudreau)

Engraved wood block marked “545” and “5-50,” used to print “Drummond’s Island Warriors” in Volume 5, page 50 of the Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition Narrative volumes. (Photo by Joan Boudreau)

To justify the more formal acquisition of the blocks into the collection, I found documentation at the Smithsonian Institution Archives about the 1960 transfer of a larger group of printing equipment from the Library of Congress.

A 1960 letter from Librarian of Congress L. Quincy Mumford to Smithsonian Secretary Leonard Carmichael referencing the transfer. (Photo by Joan Boudreau via Smithsonian Institution Archives)

Interestingly, the formal communiques documenting the transfer only mention engraved metal plates, but another SI Archives document, originally produced by a Library of Congress employee, records that on June 6, 1960: “The Office of the Secretary (SI) removed some of the surplus stock (presumed to be loose printed pages and prints), as well as the copper plates, lithographic stones, and wood engravings, relating to the Wilkes expedition …. The quiet atmosphere that usually prevails in the reading room was completely shattered that day with the reading room taking on more the appearance of a warehouse.”

The Library of Congress had been the original contractor, in 1844, for the proposed multi-volume expedition report, and the keeper of the printing equipment, in order to produce subsequent issues of the volumes. There is some evidence that the equipment had been more recently considered by the Library of Congress to be part of a group of objects sent there by the Smithsonian for safekeeping, beginning in 1860, called the Smithsonian Deposit. This consideration seems to have justified the “return” of the printing equipment to the Smithsonian in 1960.

Between the 1960s and 1980s, the subject of the proper SI collection for the printing equipment was vigorously discussed in internal communications, which also included complaints about poor management and record-keeping, hoarding situations, and suggestions to trade other collections for the metal printing plates. Even then, the Graphic Arts Collection was discussed as the logical repository for the printing equipment.

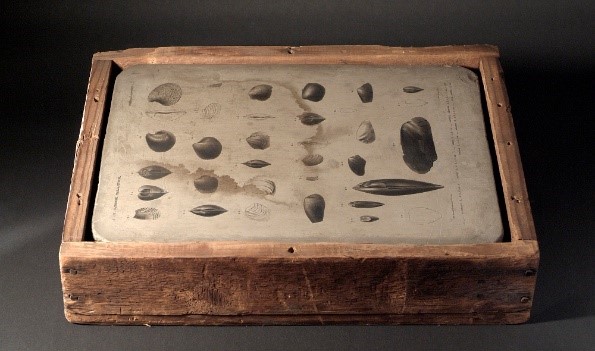

Lithographic Stone used to print Plate 9 of James Dwight Dana’s

Geology – Atlas, Volume 10 of the U.S. Exploring Expedition publications. (Photo courtesy National Museum of American History and Smithsonian Institution Archives)

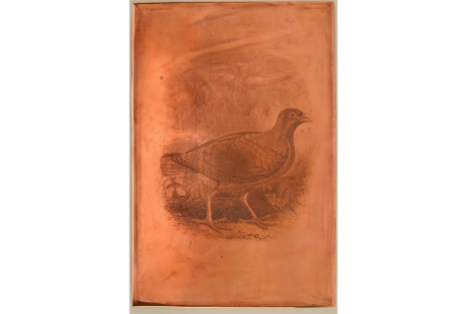

Engraved copper plate used to print Plate 34 in John Cassin’s Mammalogy and Ornithology – Atlas, Volume 8 of the U.S. Exploring Expedition publications. Pleiodus strigirostris (now Didunculus strigirostris – Tooth- billed pigeon or Samoan Pigeon). (Photo courtesy National Museum of American History and Smithsonian Institution Archives)

Engraved wood block used to print “Street View, Honolulu” in Volume 3, page 415 of the Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition Narrative volumes. (Photo courtesy National Museum of American History and Smithsonian Institution Archives)

By 1995, the three kinds of printing equipment, engraved blocks, engraved plates, and lithographic stones had found homes in three different SI collections. The engraved wood blocks were located in NMAH’s Agriculture and Natural Resources collections, the printing plates in the old downtown NMNH mezzanine location of the National Anthropological Archives, and the lithographic stones in offsite Silver Hill storage, as part of American History’s Armed Forces collections.

After my research, it seemed to be the logical next step to bring all the printing equipment together in Graphic Arts. I sent formal memos of request to the heads of the National Anthropological Archives, Armed Forces History, Agriculture and Natural Resources, as well as the SI Libraries, and SI Archives, and in due course all parties agreed.

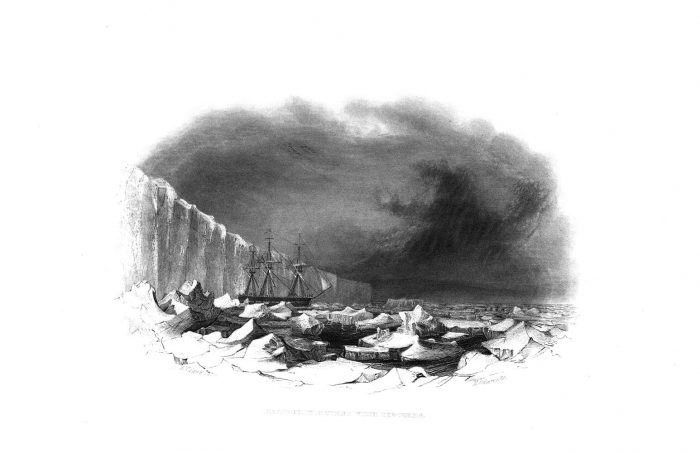

Corroded printing plate used to print “Peacock in Contact with Ice-berg” in Volume 2, page 302 of the Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition Narrative volumes. (Photo by Joan Boudreau)

Print of “Peacock in Contact with Ice-berg” in Volume 2, page 302 of the Charles Wilkes, U.S. Exploring Expedition Narrative volumes. (Photo via Smithsonian Institution Libraries)

As part of my charge, and because of the work to stabilize the rest of the collection, I consider it imperative to preserve the printing plates, some of which, the steel-faced plates especially, are corroded across the printing image surface. All but 40 of the 134 plates have been treated and preserved, and even though interest in funding the rest of the preservation effort seems to have dwindled, we continue to seek out funding sources.

Joan Boudreau is a curator in the Graphic Arts Collection, a unit of the American History museum. On the subject of the printing of the U.S. Exploring Expedition volumes Boudreau wrote “Publishing the U.S. Exploring Expedition: The Fruits of the Glorious Enterprise,” for Printing History, January 2008. Scans of the pages of the U.S. Ex. Ex. volumes can be researched on the SI Libraries page http://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/usexex/follow-01.htm

Posted: 21 February 2019

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Collaboration , Feature Stories , History and Culture