Field in Focus | Restoring America’s Prairie

With an ecosystem that supports an abundance of wildlife, from mighty bison to tiny insects, the prairie is one of North America’s greatest treasures. But decades of alterations have drastically changed this landscape and impacted the plants and animals that call it home.

Today, Smithsonian scientists are collaborating with the American Prairie Reserve in Montana to help understand, restore and preserve this wild landscape. Follow ecologists into the field as they attempt to answer big conservation questions in an even bigger place: the American prairie.

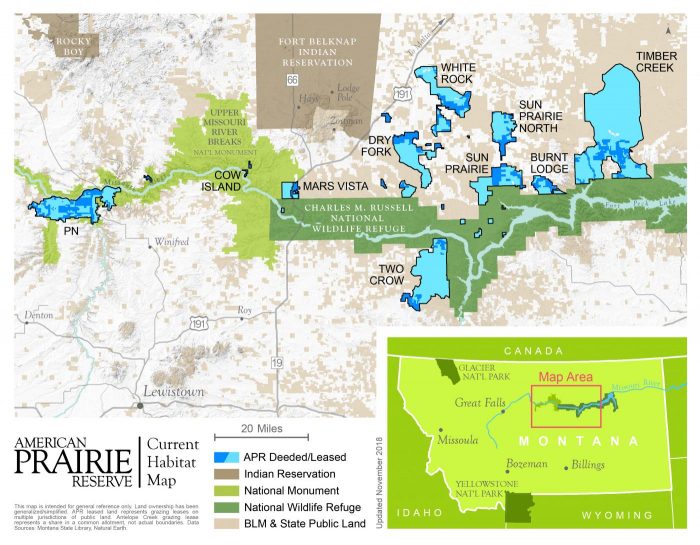

The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute (SCBI) and American Prairie Reserve (APR) are collaborating to protect and restore one of North America’s greatest treasures—the prairie. Together, they will work to better understand how changes to the grasslands affect the wildlife that call it home—from the mighty bison to the tiniest insects—and ultimately reintroduce native carnivores onto APR lands in northeastern Montana. This collaboration is made possible by the generous support of John and Adrienne Mars.

SCBI scientists will help APR study the link between land management and biodiversity, focusing on important species such as bison and prairie dogs. These landscape engineers shape the prairie ecosystem for other bird and mammal species such as burrowing owls and swift foxes. SCBI ecologists will measure the diversity of breeding birds and large mammals, map the mosaic of landscapes and test survey methods for birds and mammals. The Smithsonian’s research will be used to develop planning tools that highlight how different long-term management strategies will affect biodiversity.

Welcome to the American Prairie Reserve

Conservation biologist Andy Boyce. (Photo courtesy Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute)

My name is Andy Boyce, and I’m a conservation ecologist with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. I live on the American Prairie Reserve in Phillips County, Montana — 65 miles on gravel and mud roads from the town the Washington Post identified as the most remote in the U.S.

The hour-long trip from the nearest paved road isn’t my favorite thing in the world. It has already claimed two of my Subaru’s windshields in under eight months, but it’s indicative of what makes this place special. It’s rugged, it’s wild, it’s the size of Connecticut — and it’s one of the only places left on Earth where we have the chance to preserve a complete prairie ecosystem.

Snakes are one of a huge number of low-profile prairie residents. This eastern racer was basking in the road, so it was gently moved into the grass. Eastern Racers are nonvenomous but very, very bitey. (Photo courtesy Andy Boyce)

Almost two decades ago scientists from organizations like World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy and others realized that the conservation world had a problem. We had missed something. We’ve done a pretty good job preserving mountains and deserts around the world. We’ve done OK with forests, too. Grasslands are a different story.

Only four places remain in the world with the space and conditions for healthy populations of all grassland species, from plants to predators. Two are located in central Asia, one in Argentina and one right here on the Northern Great Plains of the U.S.

So why do prairies matter?

Grasslands, like those on and around the American Prairie Reserve, are good for growing food or growing animals for food. They are very economically productive. For this reason and others, nearly all of the large expanses of grasslands that once existed on Earth have been altered to the point that their native ecosystems are nearly unrecognizable.

Soil has been tilled, native plant communities overwhelmed with commercial crops and invasive species, and many native animals driven to local extinction (or nearly so). The bottom line is that large tracts of intact grassland ecosystems capable of supporting healthy populations of the full range of native species are exceptionally rare and in desperate need of conservation.

Here’s the good news:

This piece of Montana, between the Milk and the Missouri Rivers, is about as close as we can get to what a pristine prairie ecosystem looked like hundreds of years ago. There are huge expanses of untilled prairie, big chunks of public land already managed for the benefit of wildlife, and the vast majority of native plants and animals still flourish.

The current stewards of most of this land are ranchers, folks who grow cows to feed the rest of us. The great thing about ranching is that it doesn’t require tilling the prairie, so even areas that have been grazed for decades are still largely ecologically intact.

Map courtesy of the American Prairie Reserve. Check out an interactive version at https://americanprairie.maps.arcgis.com/apps/OnePane/storytelling_basic/index.html?appid=2b9d8f676bf44a8e813576a52be51284

Here’s the bad news:

Keystone species like bison and black-tailed prairie dogs are largely absent, victims of excessive hunting and strategic slaughter by European settlers. Predators are also mostly missing — from diminutive assassins like swift foxes and black-footed ferrets to the largest carnivores, such as grizzly bears and gray wolves.

Currently, coyotes and a handful of mountain lions sit at the top of the food chain in Eastern Montana. Grizzly bears and gray wolves once occupied this position, and their populations are slowly growing and expanding into Eastern Montana from the Greater Yellowstone and Northern Continental Divide ecosystems. (Photo courtesy Andy Boyce)

Here are the key players:

The American Prairie Reserve is acquiring huge tracts of land in this area and managing them strictly for native biodiversity, including the reintroduction of bison. Private landowner groups like the Ranchers Stewardship Alliance are partnering with conservation organizations and federal agencies to find the ideal balance between an economically sustainable business and conservation of wildlife. The combination of world-class ecological potential and difficult problems to solve is why we’re here.

Here’s what we do:

This place is not only a pristine wild landscape but also a gigantic conservation laboratory. The Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute is here to study how the reintroduction of keystone species influences the biodiversity of the entire ecosystem. We are also here to lend our expertise to reintroductions of species like the swift fox and black-footed ferret.

And here’s how we do it:

As a conservation ecologist, I wear a lot of hats. My biggest responsibility is to translate scientific questions into action. We want to know how the reintroduction of American bison influences biodiversity, so how do we find out?

We train interns to identify birds, plants and mammals, so they can get out there and gather diversity data across a vast landscape. We teach them to set up camera traps to capture consistent and high-quality animal images. We show our interns how to drive, hike, operate ATVs and navigate a huge and often unpredictable place.

Gathering data is just the first step. Once fall turns to winter, it’s my job to translate these data into conclusions. What did we find out? What do I need to change for next year? The last step is communication. Results and conclusions need to be published in scientific journals to quickly spread the word about what we’ve discovered.

Reaching people outside of the academic world is important too, including land managers, legislators and the general public who are interested in the wellbeing of wildlife and the people living alongside them.

The American Prairie Reserve currently hosts four herds of American bison, or plains bison (Bison bison bison), on their lands — a total of approximately 850 individuals.

On paper these projects sound straightforward, but ecological research is anything but quick and easy. Answering big questions in an even bigger place takes time, hard work and hundreds of tiny successes and failures.

How do you measure biodiversity across an area the size of Connecticut? What happens when every road within 50 miles turns to wet cement? How on earth do you keep curious, itchy, 2,000-pound bison from destroying all of your equipment?

Stay with us to see conservation at work, to get to know the landscape and the species that make this place special, and to meet the people who make it all possible.

This post by Andy Boyce was originally published by Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute.

Posted: 2 April 2019