May Day: America’s most traditional, radical, complicated holiday

From its earliest origins as a Roman festival of spring, May Day has evolved to celebrate everything from pagan fertility to the rights of the working man to a showcase for militaristic strength. Jordan Grant explores the complicated history of the holiday.

May Day celebration, 1940. Courtesy of Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company Records, 1907 – 1948, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

May Day is a holiday that many Americans have celebrated, but relatively few can explain. Depending on your age, you might associate May 1 with dancing around a maypole in elementary school or watching tanks proceed through Moscow’s Red Square on the evening news. Surprisingly, much of the confusion that surrounds May Day in the modern United States can be traced back to the late 1800s, when America’s wealthiest classes and its working classes battled over what the holiday would mean for future generations.

The roots of May Day go all the way back to ancient world. For the Romans, the first of May stood at the heart of the Floralia, a weeklong festival to honor Flora, goddess of youth, spring, and flowers. When the Romans reached the British Isles, their Floralia festival collided with the Celtic holiday of Beltane, also held on May 1. Elements of both celebrations combined to lay the foundations for what became known as May Day—which, by the medieval period, had become a cherished holiday throughout Europe.

Every year, villagers would go “a-maying,” venturing out in the early morning to collect flowers and decorate their town for the day’s festivities. During the day, villages would hold a number of games, pageants, and dances, and many would crown a young woman “May Queen” to preside over the fun. At the heart of the festivities stood the maypole. Pulled into town by a pair of flower-adorned oxen, the pole (usually cut from a birch tree) was raised and decorated with colorful streamers that villagers could hold as they danced.

Although England’s May Day celebrations suffered a slight setback when Parliament temporarily banned maypoles during the English Civil War, the holiday returned in full force with the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660. Still, May Day initially received a chilly reception in colonial America. Puritan colonists in New England frowned on the spring holiday and its maypole, criticizing the latter as thinly veiled form of idolatry. When the Anglican merchant Thomas Morton erected a maypole on Merry Mount plantation in 1627, officials from the neighboring Puritan town broke up the celebration, chopped down the pole, and promptly sent the merchant back to England. Morton described his May Day accident in his 1637 book, the New English Canaan, and the story later became the inspiration for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story The May-Pole of Merry Mount.

May Day celebration around 1936. Courtesy of Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company Records, 1907-1948, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

May Day might have remained an obscure holiday in the United States if not for the work of two very different groups of reformers in the late 1800s, both of whom were concerned about the welfare of America’s working classes. The first group were social reformers plucked from the nation’s wealthiest and most powerful families, a group that historian David Glassberg memorably describes as the nation’s “genteel intellectuals.”

May Day celebration, around 1936. Courtesy of Pittsburgh Consolidation Coal Company Records, 1907 – 1948, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

In the late 1800s, migrants and immigrants from around the world were flocking to U.S. cities to find jobs in the nation’s booming industries; from their vantage point at the top of the social ladder, America’s genteel intellectuals looked down at these teeming masses with trepidation. Many feared that workers, exhausted as they were from factory work and the stresses of urban life, would fall victim to the cheap commercial amusements of the day—carnivals, penny arcades, and amusement parks, entertainments that (so the argument went) stimulated the body but did little to educate the mind or instill “traditional” American values.

Miss Anna Jackson’s May Day in Washington, D.C., 1942. Courtesy of Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905 – 1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

For wealthy reformers, the solution was to give workers more opportunities for wholesome play, particularly play that was steeped in the nation’s white Anglo-Saxon past. May Day, after languishing in the background of the American psyche for centuries, stood out as an ideal candidate for a revival. The resurgence of May Day traditions began in the 1870s on women’s college campuses, where the children of wealthy families donned white outfits, danced traditional folk dances and, in many cases, performed dramatic retellings of the story of Thomas Morton and his doomed maypole. To popularize May Day among the masses, wealthy reformers also introduced the traditions of “a-maying” to American schoolchildren. Generations of students in public and private schools, many of whom came from immigrant families, were taught to gather flowers and dance around the maypole on the first of May.

The May Queen at Miss Ana Jackson’s May Day in Washington, D.C., 1942. Courtesy of Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 1905-1994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

At the same time as elite reformers were busy resurrecting May Day’s traditional past, labor leaders from the nation’s working classes were trying to redefine May 1 as a holiday set aside for the American laborer. When industrialization took off in the late 1800s after the Civil War, workers organized into unions and joined pro-labor organizations in order to gain bargaining power, elect sympathetic politicians, and generally protect their interests. One of the earliest rallying points for labor organizations was the fight for the eight- hour work day. In the 1880s most workers still worked a daily shift of 10 or more hours, six days a week (or half a day on Saturday).

In Chicago, 44 unions took to the streets on May 1, 1867, to celebrate the passage of an eight-hour workday law in Illinois. The next day, thousands of workers struck, staying home from work in an act of solidarity. Although the 1867 law was never enforced, the city’s workers preserved the memory of their predecessors’ short-lived victory. Years later, at its 1885 convention, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Assemblies (a predecessor to the American Federation of Labor, or AFL) selected May 1, 1886, as the date for a universal strike to press for an eight-hour workday. According to the historian Donna T. Haverty-Stacke, labor leaders’ decision to stage their protest on May 1, 1886, probably had little to do with the May Day’s significance as a spring holiday. Instead, leaders at the time associated the day with Chicago’s earlier protests in 1867 and, even more directly, the fact that May 1 was traditionally when union contracts and housing leases expired in U.S. cities.

On May 1, 1886, more than 30,000 Chicago workers struck. Unions and labor organizations from the across the political spectrum organized parades and mass meetings, and workers in other industrialized cities like New York and Cincinnati took up the cause, marching in the streets to draw public attention to their demands and convince other laborers to join the fight.

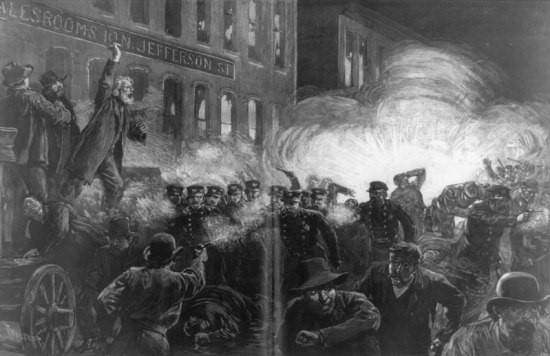

Unfortunately, the triumphs that workers celebrated on May Day 1886 were quickly overshadowed by violence. On May 3, members of the Chicago police fired at a group of striking workers at a McCormick reaper plant, killing at least two. The next day, when laborers staged a protest meeting in Haymarket Square, a protester hurled a bomb at the police, killing one and injuring dozens more. For many Americans at the time, the “Haymarket incident” and the contentious public trials that followed sullied May 1, forever tying the day to anarchists, socialists, and other “radical” groups that stood outside the mainstream of American society.

“The Anarchist Riot in Chicago” published in the May 15, 1886 edition of Harper’s Weekly. Courtesy of Library of Congress

In 1889, just as public opinion about May Day within the United States was shifting, the labor holiday went international. When the International Socialist Congress met in France that year, its members adopted a resolution to hold a “great international demonstration” on May 1, 1890, to coincide with protests that had already been scheduled by the AFL. Their resolution sparked a series of demonstrations across Europe. In the years that followed, European workers embraced May 1 wholeheartedly—so much so that by the end of the century most Americans associated May Day with international socialism rather than the homegrown unionism that had set the holiday in motion. Wary of any association with radicalism, more conservative unions in the U.S. dropped the May 1 holiday entirely in favor of celebrating Labor Day in early September.

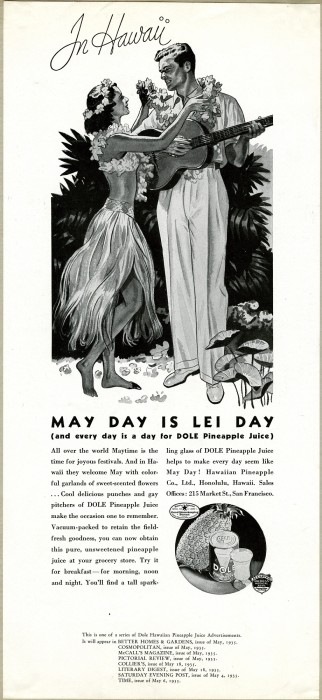

The meaning of May Day in the United States continued to change throughout the 1900s. In Hawaii, Lei Day was made an official state holiday in 1929, combining May 1st’s established association with flowers with Hawaii’s traditions surrounding the lei. “May Day is Lei Day” advertisement courtesy N.W. Ayer Advertising Agency Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History.

In the early 1900s, it may have appeared that the nation’s wealthy reformers had won the day. Traditional maypole celebrations were a common May Day attraction in the nation’s colleges and schools, while militant protests and strikes were only pursued by socialists, communists, and the most militant unions. Viewed with hindsight, however, the elites’ victory seems far less assured. While countless Americans did (and continue to) celebrate May Day in the traditional English style, it would be quite a stretch to say that these festivities displaced any of the popular amusements that so worried genteel intellectuals. And while the significance of May Day as a labor holiday dimmed in the United States, that celebratory energy has been more than replaced by the millions of workers who continue to make the first of May International Workers’ Day. In the case of American workers, the loss of May Day did not end the struggle for better treatment. Laborers continued to strike, march, and celebrate—just on different days of the year.

Jordan Grant is a New Media assistant working with the American Enterprise exhibition, located in the Mars Hall of American Business at the American History Museum. This article was originally published in two parts by the blog, O Say Can You See?

Posted: 1 May 2019

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture