Secretary Lonnie Bunch weighs in on legendary photo archive of African American life

In an historic moment, foundations and museums came together to rescue black history. “This is an optimistic tale,” says Bunch.

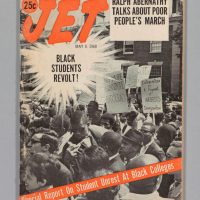

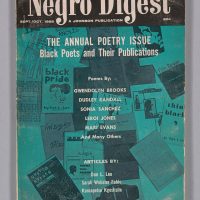

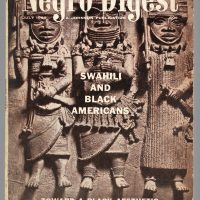

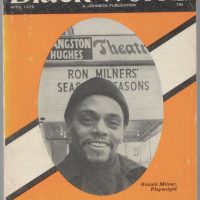

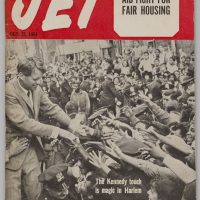

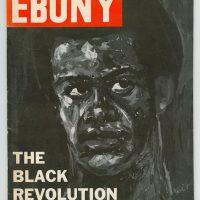

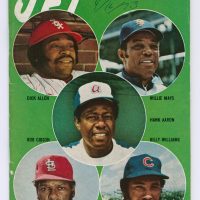

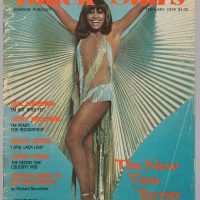

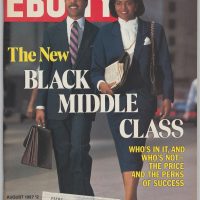

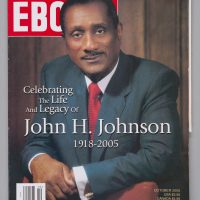

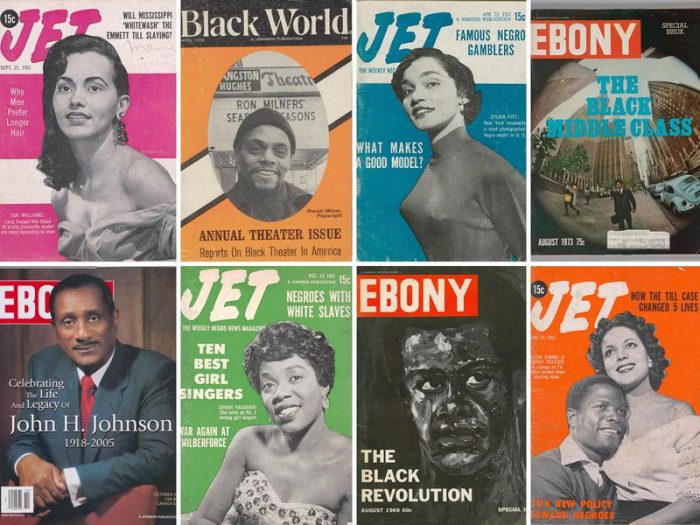

The company’s publications (includingBlack World,, EbonyJet) reached a wide audience with photo-driven narratives and interviews. (NMAAHC, © Johnson Publishing Company)

A hand-wringing bankruptcy auction put the fate of one of the most significant collections of 20th-century photographs documenting the African-American experience up in the air. More than 4 million prints and negatives that make up the storied legacy of the Johnson Publishing Company, the parent company of essential black publications, including Ebony and Jet, were put in jeopardy, after the company filed for Chapter VII bankruptcy this past spring.

Now, a consortium of four institutions, including the Ford Foundation, the J. Paul Getty Trust, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, have come together to acquire the legendary archive. The foundations will donate the archive to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Getty Research Institute and other leading cultural institutions, ensuring that the collection will be available for unprecedented scholarship and visibility.

“This archive, especially photographically, is the archive of record for black America from immediately after the Second World War probably until the 1970s or early ’80s,” says Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch. “Almost any story that has touched black America, whether it’s celebratory, whether it’s tragedy, that is material that we expect to be in there. So this is really an opportunity to understand a full range of the African-American experience.”

Founder John H. Johnson modeled his publications (beginning with the Negro Digest in 1942, followed shortly after by Ebony in 1945 and Jet in 1951) on glossy white mainstream magazines like Look and Life, but for a black audience. The publication’s photo-driven narratives and interviews shared “positive, every day achievements from Harlem to Hollywood,” though, as the Chicago Sun-Times reported, when it came to racism—the “No. 1 problem in America”—they would “talk turkey.” That made the publications essential reading for the African diaspora in the United States, leading to sayings, like: “If it wasn’t in Jet, it didn’t happen.” Johnson’s wife, Eunice, further expanded the Johnson Publishing empire in her own right, through the launch of additional businesses such as an annual fashion show and a cosmetic line.

- Jet, Sept. 15, 1955 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Jet, Sept. 22, 1955 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Jet, Sept, 29, 1955 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

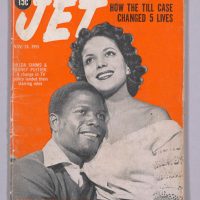

- Jet, Nov. 24, 1955 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Jet, May 9, 1968 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Negro Digest, Sept-Oct. 1968 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Negro Digest, July 1969 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

-

Black World, April 1976

(NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

But like so many flagship publishers, the company struggled in the Internet age. Desirée Rogers, who served as CEO from 2010 to 2017 and Johnson’s daughter Linda Johnson Rice, did their best to keep the company afloat, but finally in April, Johnson Publishing filed for Chapter VII. Ebony, Ebony.com and Jet.com were unaffected by the sale, as they had been previously sold to a private black-owned equity firm. But, as part of the auction of Johnson Publishing’s assets, the storied photography archive had to be divested.

The archive, which was initially offered for sale in 2015, when it was appraised at $46 million, tells the history of the African-American experience through some 70 years of photographs. It includes household names—like that of Ray Charles, Dorothy Dandrige, Aretha Franklin, and so on—as well as names neglected by the white press. And while Johnson was known to favor feel-good stories, he published on his pages photographs documenting the brutalities African-Americans faced (most notably, court filings state that the collection contains as many as 80 images of the funeral of Emmett Till, the African-American boy from Chicago who was tortured and murdered while visiting family in Mississippi).

In American Historical Association’s magazine, Perspectives, Allison Miller sounded the alarm on the implications of selling such an archive to the wrong buyer. Handwringing ensued. But no winner was announced when the auction took place last Wednesday; instead, at the time, a statement by Hilco Streambank, which was conducting the auction, announced that the auction would be adjourned until this Monday “to consider additional pending offers.” That window gave the four institutions, the Ford Foundation, the J. Paul Getty Trust, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the time they needed to move forward with a last-minute offer.

The partnership only came together last week, according to the New York Times’ Julie Bosman. Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, read about the news of the pending auction on his phone while in Spain. Concerned about the fate of the photographs, he emailed Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Mellon Foundation, and asked what could be done. Lightning fast by corporate standards, the foundations came together with a plan.

- Jet, )ct. 22, 1964 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Jet, May 9, 1968 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Ebony. August 1969 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Jet, April 19, 1973 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Black Stars, February 1979 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Ebony, August 1987 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Jet, Dec. 19, 1988 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

- Ebony, October 2005 (NMAAHC © Johnson Publishing Company)

“We received the call from Darren Walker, [president] of the Ford, who knew of our interest, of my personal interest, and asked if we wanted to be a partner, and with the Getty to be responsible for the bulk of the collection. I paused for, oh, at least four seconds, and then I said, ‘yes,’” says Bunch, who until his recent appointment as the Smithsonian Secretary was the founding director of the African American History Museum.

This week, the foundations successfully placed the winning bid of $30 million, subject to bankruptcy court approval.

Donating the Johnson Publishing photo archive to the Smithsonian’s African American History Museum and the Getty Research Institute will make the collection more accessible than ever before to scholars and the public.

While Johnson Publishing didn’t close its doors to researchers, as a private business, it could choose who came in and out, and only few over the years had been given access to its “inner sanctum,” as Brenna W. Greer, an associate professor of history at Wellesley College who writes about race, business and visual culture, told Miller.

No longer. “The one thing I know as a historian is that often history is lost,” says Bunch. “It’s lost with the trash. It’s lost with fires. And it’s lost when businesses are no longer able to maintain themselves. So I think it’s important to remember that part of the goal of the Smithsonian is to not just collect, but to help other places preserve so that we make sure that the stories of history are really never lost.”

Though he can only speak in broad generalizations when it comes to the archive, he says that the goal “is to make significant parts of it accessible in a reasonable amount of time.” That means not just digitization, but, likely, exhibitions, traveling shows, publications and symposia. “This is really an opportunity to bring the best of Smithsonian, to make a story that is best known by some better known by all,” he adds.

The Getty has announced similar plans to ensure that in the years to come the general public and scholars will have free access to see and study the images.

Addressing the saga of the Johnson Publishing photo archive, Bunch says it doesn’t have to be seen as a cautionary tale. “I think, for me, this is an optimistic tale,” he says, “a tale of foundations and museums coming together to rescue something that is crucially important to this country.”

This article by Jacqueline Mansky was originally published by Smithsonian.com. Mansky is the assistant web editor, humanities, for Smithsonian magazine.

Copyright 2019 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 29 July 2019