Seven things you didn’t know about the Star-Spangled Banner

Everyone knows Betsy Ross made the Star-Spangled Banner, right? Well, everyone is wrong. Celebrate Flag Day by learning seven little-known facts about the flag that inspired the National Anthem.

The Star-Spangled Banner is one of the most recognizable icons of the United States. Huge, vibrant, and rich in history, most Americans are familiar with the story of this particular flag: It’s the one that flew over Fort McHenry the morning after the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812 and inspired Francis Scott Key to write the words that would one day become our national anthem. Although this flag has been around for 200 years now, there is more to this story that begs to be told.

The Star-Spangled Banner has a sibling, and we have no idea where it is.

In 1813, Mary Pickersgill, a Baltimore flag maker, was commissioned to make two flags for Fort McHenry. In addition to the gigantic 42 x 30 foot garrison flag (now the Star-Spangled Banner), Pickersgill and the young women who helped her also sewed a smaller “storm flag.” Coming in at 17 x 25 feet, this storm flag was much smaller and was designed to withstand tough weather, such as the raging winds and pouring rain that occurred during the Battle of Baltimore.

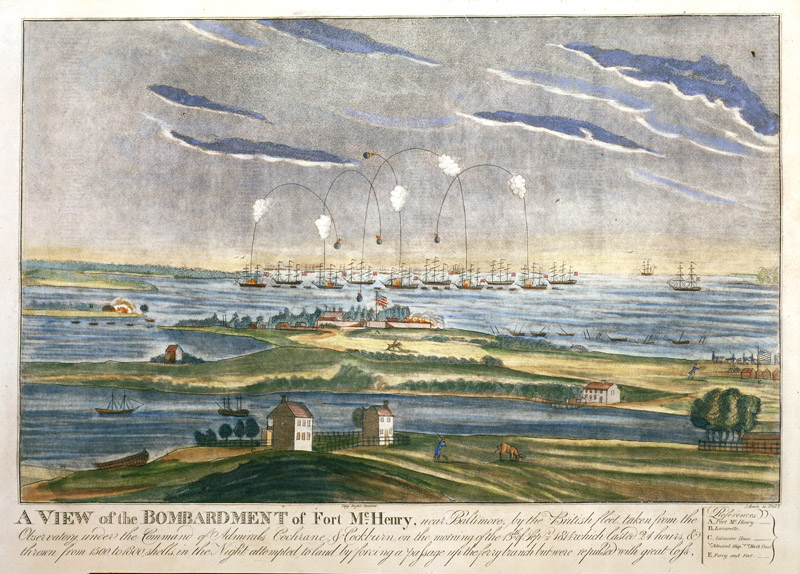

A View of the Bombardment of Fort McHenry. Print by J. Bower, Philadelphia, 1816. One of the soldiers who was in the fort during the 25-hour bombardment wrote, “We were like pigeons tied by the legs to be shot at.”

Two eyewitnesses—a British midshipman out in the harbor and an American private inside the fort—recounted seeing a flag being raised above the fort in the morning, so the logical conclusion is that the garrison flag seen that morning was not flying during the battle itself. However, scholars continue to debate whether the storm flag flew during 25-hour bombardment. In February 1815, the storm flag was lost to history after being replaced by a new one from the Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia.

There were more than 15 states when the flag was made, but there are only 15 stars on the flag.

No, Mary Pickersgill did not make a mathematical error. The flag’s design was last approved by Congress in 1794, providing for 15 stripes and 15 stars. This was not updated until April 4, 1818, so Pickersgill sewed on 15 stars.

Each star, by the way, is made of cotton and was created by reverse applicqué method. Each star was stitched into place on one side of the flag and the cloth on the reverse side was then cut away to reveal it.

The same family that kept the Star-Spangled Banner safe during the Civil War also sympathized with the Confederacy.

After the death of Col. George Armistead, who was commander of Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore, the flag passed to his daughter Georgiana Armistead Appleton. Georgiana found herself on the wrong side of the battle lines when the Civil War broke out. Although she lived in Maryland, a Union state, her sympathies lay with the Confederate cause. Her son George was even arrested in 1861 for trying to sneak into Virginia to join the Confederate Army.

Georgiana Armistead Appleton, George Armistead’s daughter, inherited the flag upon her mother’s death in 1861. As its guardian and devoted champion, she encouraged its display at patriotic celebrations. Courtesy of Christopher Hughes Morton.

Despite their feelings about disunion, the Armistead family made a specific effort to protect the flag that symbolized a preserved and united nation. It is likely that they kept the flag hidden in their home in Baltimore for the duration of the war, but Margaret Appleton Baker, Georgiana’s daughter, told the New York Herald in 1895 that the flag had actually been sent to England. As internationally intriguing as her story is, there is no evidence to support Margaret’s recollections and historians agree the flag probably remained in Baltimore.

After coming to the Smithsonian, the Star-Spangled Banner has only left the National Mall once.

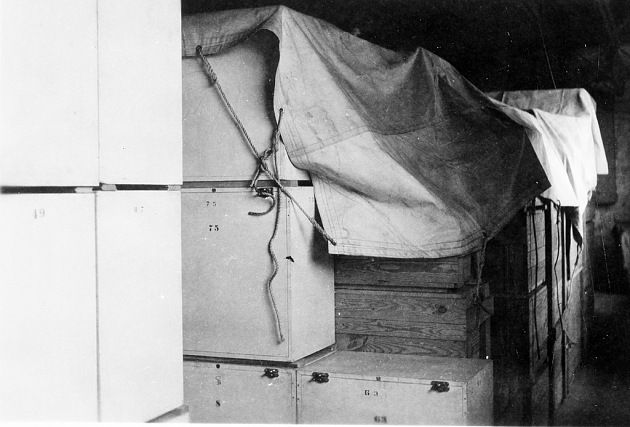

Only twice in its history has the Star-Spangled Banner been hidden away to keep it safe from war, though America has fought many more wars than that since 1814. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Americans once more felt their homeland might be under real physical threat. As World War II began, plans were made to protect a number of the Smithsonian’s most precious objects. The flag and many other treasures were crated up and sent to Luray, Virginia, for safekeeping.

In this photo from the Smithsonian Archives, Smithsonian collections are crated and covered with a tarp to be transferred to a storage facility in Luray, Virgina, for safekeeping during World War II.

According to the Smithsonian Archives, this October 1944 photograph shows: “The headquarters area of the United States National Museum storage facilityin Luray, Virginia, near Shenandoah National Park.” On the back of photograph it states: “Nat. Museum collections stored in building having dormer windows.”

The Star-Spangled Banner flag is on display at the National Museum of American History. And it’s never leaving.

Museums often lend objects and artifacts to each other in order to tell more complete stories. In the case of the Star-Spangled Banner, however, that will likely never happen. In 1912, Georgiana Armistead Appleton’s son Eben Appleton decided to give the Star-Spangled Banner to the Smithsonian as a permanent gift. In 1913, the National Star-Spangled Banner Centennial Commission in Baltimore asked to borrow the flag for their celebration. Eben immediately wrote to the Secretary of the Smithsonian, Charles D. Walcott. “I gave the flag to the National Museum with the firm and settled intention of having it remain there forever,” he wrote, “and regarded the acceptance of the gift by the Authorities of the Museum as evidence of their willingness to comply with this condition…” Eben asked Walcott to ensure that any “citizen who visits the museum with the expectation of seeing the flag be sure of finding it in its accustomed place.”

In this 1993 photo from Smithsonian Archives, the flag is shown inside the museum’s center hall. Today, it’s in a special low-light chamber where you can see it 364 days per year.

The museum removed 1.7 million stitches (a previous preservation attempt) from the Star-Spangled Banner.

The short video below introduces a method used by Amelia Fowler, who was hired in 1914 to help preserve the flag. Undoing her work required unbelievable precision.

During the Civil War, the Union flag continued to include a star for each state in the Union—even those states that had seceded.

Although states seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States of America, the U.S. flag remained unchanged. President Abraham Lincoln maintained that those states never really left the nation but were merely in rebellion. Keeping their stars on the national flag signified that continued solidarity. In fact, the number of stars on the flag actually grew during the war from 34 to 36. West Virginia and Nevada joined the Union in 1863 and 1864 respectively. The Confederate States of America chose a pattern for their national flag that is strikingly similar to the Star-Spangled Banner, the flag of the Union. When Confederate soldiers carried their national flag into battle, its stars and stripes led to confusion—especially when the smoke and wind of battle wrapped the flag around its staff. The Confederate Army eventually adopted the Confederate battle flag in order to avoid potentially lethal confusion.

The Confederate States of America’s first national flag was also known as the “Stars & Bars.” This flag flew from 1861 to 1863. Each of the eight stars represented a Confederate state in March 1861 when the flag was adopted.

This post, originally published by the American History Museum blog, O Say Can You See?, was written by Victoria “Tory” Altman, an Education Specialist in the Office of Education Outreach. She recommends you brush up on more flag facts by learning about the flag’s most recent conservation check-up and finding out why the national anthem is so hard to sing.

Posted: 4 July 2019