The secret lives of bees…and birds and dragonflies and grasshoppers and gardeners

What better way to spend a sultry summer day than with a stroll down a garden path? Marisa Scalera leads a tour of Smithsonian Gardens’ “Habitat.”

Smithsonian Gardens Landscape Architect Maris Scalera (Photo by John Barrat)

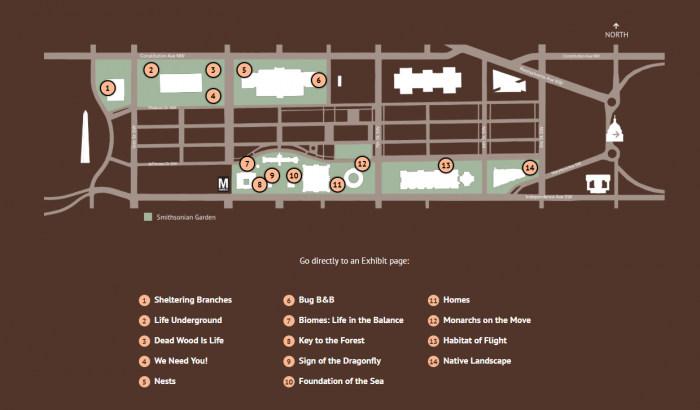

As the crow flies it’s one mile from the northwest corner of the grounds of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (15th Street and Constitution Ave., N.W.) on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to the southeast corner of the property that surrounds the National Museum of the American Indian (3rd Street and Maryland Ave., S.W.). Across this busy public campus some 14 different outdoor and indoor areas maintained by Smithsonian Gardens are traversed by millions of visitors annually who travel by foot, scooter, stroller, skateboard and bike, constantly moving back and forth across the Mall en route to its many museums and monuments.

In May, Smithsonian Gardens launched a single exhibition, “Habitat,” uniting these diverse areas under one visual identity and theme: Protecting habitats protects life. John Barrat took a walk with Smithsonian Gardens’ Landscape Architect Marisa Scalera to learn more about how Smithsonian Gardens carried out this impressive feat.

“Habitat” seems pretty ambitious. Is this the first time Smithsonian Gardens has carried out a project of this magnitude?

Marisa Scalera: Yes. “Habitat” is our inaugural exhibit and is big news for Smithsonian Gardens. In 2013 we changed our name from the Office of Horticulture Services to Smithsonian Gardens, developed a new strategic plan and were named an accredited museum by the American Alliance of Museums. “Habitat” is the next step in this intentional evolution as we grow into our new role as an accredited museum. Two and a-half years ago we started working with Smithsonian Exhibits on the creation of an interpretive master plan, one of the main features of which is a series of campus-wide exhibitions. “Habitat” is the first in this series.

Our aim with this exhibit was to have one consistent look and one consistent voice across all our gardens. To achieve this, we worked with one writer, John Powell from Smithsonian Exhibits, and one outside graphic designer. In time, we expect exhibitions like “Habitat” to tie all our exterior and interior garden spaces together, giving us a very recognizable identity.

If you mention Smithsonian Gardens today, some people think only of the Enid A. Haupt Garden, others of the U.S. Botanic Garden, which, of course, is not even part of the Smithsonian. People don’t necessarily have a good idea of what the components of Smithsonian Gardens are. In time our work will change that.

You mentioned that the Enid A. Haupt Garden is perhaps the most well-known Smithsonian Garden. Can you point out the “Habitat” components in this garden?

Here in the Haupt Garden we have installed three different exhibits that go together, each focusing on a key concept ecologists and conservationists use in their work.

Indicator species

In the Haupt’s Moongate Garden, the featured concept is indicator species, and we use dragonflies as an example. Dragonflies are indicator species for the health of a wetland. If a wetland is healthy and its water quality good, then dragonflies will be present. If dragonflies are not present, it may be an indication of poor water quality.

Sign of the Dragonfly exhibit, Enid A. Haupt Garden (Image courtesy of Smithsonian Gardens)

Sign of the Dragonfly exhibit (Enid A. Haupt Moongate garden) Photo by John Barrat

I’d like to point out the dragonfly models you see here were designed entirely in-house. The initial concept was developed by horticulturist Shelley Gaskins. Shelley and I worked with worked with Smithsonian Gardens’ staff entomologist Holly Walker to get the proper angles for the dragonfly wings and our staff then drew up the models with the design program Autocad. Next, the designs were sent to a fabricator who cut them out from 3/8-inch thick aluminum. A second fabricator bent the wings and painted the models with auto body paint, which gives them their slight iridescence.

Foundation species

A second concept, foundation species, is featured in the Haupt’s Fountain Garden. Using spaghetti stone, living succulent plants and other elements, Gardens staff created a colorful coral-reef sculpture. Coral is a foundation species in that it provides a habitat for other species to live. Beavers are another foundation species in that they create dams which provide habitat for other species.

Foundation of the Sea exhibit, Enid A. Haupt Garden (Image courtesy of Smithsonian Gardens)

Keystone species

Keystone species is the third concept highlighted where the Haupt Garden borders the Freer Gallery. Keystone species are species of great importance to many other species in an ecosystem. The green-backed Firecrown hummingbird, for example, pollinates nearly 20 percent of the woody plants in the forests of Patagonia at the southern tip of South America.

These three elements tie together different areas of the Haupt Garden, as well as connect it to the much larger “Habitat” exhibit spread across other Smithsonian landscapes areas on the Mall. The American History Museum, for example, has several large showy wooden sculptures created by artist Foon Sham. There are insect sculptures and large models of bird nests at Natural History.

Life Underground exhibit, outside the National Museum of American History.

Sculptor: Foon Sham “Mushroom”, 2019

12’ height x 11’ diameter, elm, cypress, oak, birch, and katsura sourced from Smithsonian Gardens

campus. (Image courtesy Smithsonian Gardens

Dead Wood is Life exhibit (Outside of the National Museum of American History)

Sculptor: Foon Sham “Arches of Life”, 2019

62’ long x 14’ height (max) pine. Sculpture courtesy of Gallery Neptune & Brown (Image courtesy of Smithsonian Gardens)

Bug B&B exhibit (outside the National Museum of Natural History) Image courtesy of Smithsonian Gardens

Nests exhibit (outside of the National Museum of Natural History) Image courtesy Smithsonian Gardens

Do all areas of the “Habitat” exhibit contain sculptures?

No, for instance, outside the Air and Space Museum we created a “Habitat of Flight” exhibit that includes signage focusing on how humans have been inspired to experiment with flight through observations in nature: the wings of different birds, insect flight and how plant seeds are dispersed by wind. In addition to the signs, we created sort of an oasis for visitors, placing aluminum tables and chairs interspersed with maple trees in large green planters, along a linear garden beside the museum where visitors can stop and relax. From day one people have been crowding this area.

Because the Air and Space Museum is under construction we worked closely with museum construction managers to choose a location easily accessible and visible to visitors: the northeast side of the museum right near the entrance.

Habitat of Flight exhibit (outside National Air and Space Museum) Image courtesy of Smithsonian Gardens

Like the Air and Space Museum site, other “Habitat” exhibit locations we chose are in places that didn’t see many visitors previously. So, we have created places in our landscape for visitors to gather that didn’t really exist before. In turn, these places have visitors interacting in new ways with the landscapes maintained by Smithsonian Gardens.

How did the concept for the “Habitat of Flight” signage come about?

A team of us worked it up. Lead horticulturist Alex Dencker is the one who came up the initial idea for this and he then met with Cindy Brown, our Collections and Education manager and me, as project manager, to discuss it, and then we met with Smithsonian Exhibits. We then ran all of this by the Air and Space Museum to get their feedback on it and they had some refinements. So, it was very much a collaborative process.

I particularly love this exhibit sign “Different Wings for Different Birds” because it relates back into habitat, as well as into the content of the museum, talking about different wing shapes for different birds, how its different wing shape allows a bird to thrive in a specific habitat and then how those wing shapes are like the wings of certain aircraft on exhibit inside the museum.

Habitat of Flight exhibit, outside National Air and Space Museum. Photo by John Barrat.

Backyard gardeners should be pleased to come across the “Habitat” content of the Mary Livingston Ripley Garden.

The “Habitat” content in the Ripley Garden [between the Hirshhorn and the Arts and Industries Building] is very much aimed at the home gardener. Two years ago, when we were planning this exhibition we developed three key messages to convey to our visitors: Habitats are homes, habitats are interconnected, and habitats are fragile and need to be protected.

The Ripley Garden signage really emphasizes that first message: how to make your own home garden into a habitat. It looks at food, shelter, water and ways to incorporate these elements into a home garden in new attractive ways, ways that will transform your home garden into a wildlife habitat. You can see Janet Draper, Smithsonian Gardens’ horticulturalist for the Ripley Garden, has really filled it with bird baths, bird houses, different forms of insect hotels, and pollinator friendly plants, all ideas to encourage insects and other animals to move in and make your home garden their home.

Homes exhibit, Mary Livingston Ripley Garden. Image courtesy Smithsonian Gardens.

Homes exhibit, Mary Livingston Ripley Garden (Image courtesy of Smithsonian Gardens)

You mention creating insect habitats, but not all bugs are good for gardens. How do you control pests?

We do use chemical pesticides, but we are very conservative in their use. We prefer instead to focus on cultural, mechanical, and biological controls first and only use chemical controls as a last resort. Holly Walker, our plant health specialist, has a doctorate in entomology and she is dedicated to using the least harmful solutions that are also part of a more sustainable big picture.

“Habitat” will be on view throughout the Smithsonian campus until 2020.

Posted: 2 July 2019

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , Science and Nature