We all know about Apollo 11, but what about the other Apollo missions?

The crew of Apollo 10, from left to right: lunar module pilot Eugene A. Cernan, commander Thomas P. Stafford, and command module pilot John W. Young. (NASA)

Smithsonian curator Michael Neufeld reflects on Apollo 10, the mission that made landing on the moon possible.

On May 18, 1969, the astronauts who crewed the “dress rehearsal” for Apollo 11 paved the way for history to be made just a couple months later

“I keep telling Neil Armstrong that we painted that white line in the sky all the way to the moon down to 47,000 feet so he wouldn’t get lost, and all he had to do was land. Made it sort of easy for him.”

So said Eugene Cernan, the last human to set foot on the moon, and before that, the lunar module pilot of Apollo 10. Along with commander Thomas Stafford and command module pilot John Young, Cernan crewed the critical dress rehearsal, the mission to do “everything but land.”

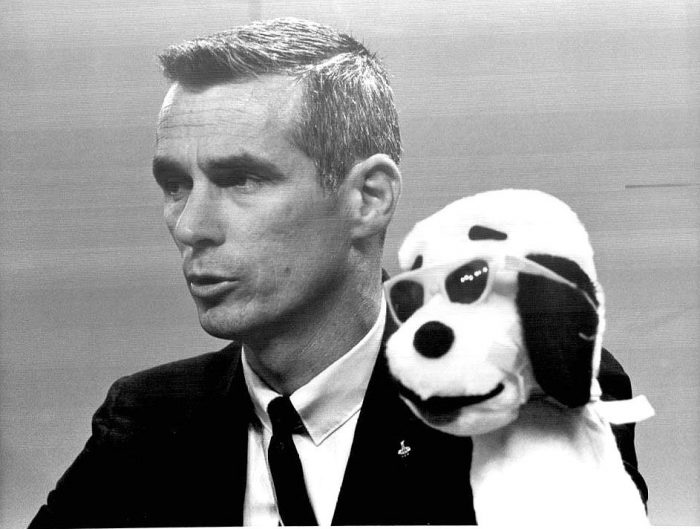

Apollo 10 lunar module pilot Gene Cernan at an April 26, 1969 press conference with a puppet of Snoopy, which along with Charlie Brown from the comic Peanuts, became a mascot for the mission. (NASA)

Apollo 10 will forever serve as the crux between two of the most extraordinary accomplishments in human history: the first flight to the moon on Apollo 8, and of course, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin’s first steps on the lunar surface during Apollo 11. The mission was the last chance to test the critical hardware and software that would take people to the moon, including the all-important lunar module, which was making its first trip to lunar orbit. On the next, it would land.

Fifty years after the launch of Apollo 10—the mission that is often said to have taken people farther from Earth than ever before or since—we can gain a new perspective on the lunar flight’s place in history. Smithsonian spoke with Michael Neufeld, senior curator of the space history department at the National Air and Space Museum, to talk about Apollo 10’s role in the program that launched the first flights to another world.

Apollo 10 came right in the heart of the Apollo program, as NASA was gearing up for the first lunar landing attempt. What had happened immediately before, on Apollo 9?

The fundamental purpose of Apollo 9 was to test out the lunar module. It was the first time humans flew it. But also the mission was an Earth-orbit rehearsal for the lunar landing. They simulated in Earth orbit as best they could the whole lunar landing and return sequence. So that was a really important test.

Another thing that happened on Apollo 9 that’s interesting is that it’s the only time before Armstrong stepped down on the moon that they had someone go outside on the porch of the lunar module with the portable life support system backpack. [Russell “Rusty”] Schweickart got outside and demonstrated that the backpack worked.

When they flew to the moon on Apollo 10, it was the first time the lunar module (LM) would make the trip to lunar orbit. Were there any remaining questions about how the LM would perform once they brought it all the way to the moon?

I don’t think they were too concerned about the environment. The LM flew successfully once with humans, and once on Apollo 5 without humans. But it was still a very new vehicle, so they did not want to commit to a lunar landing on the very next mission.

Apollo 10’s purpose was to do a full dress rehearsal of the lunar landing, so they effectively carried out a practice run on the Sea of Tranquility landing site, including photographing the landmarks, seeing when the various craters came up, carrying out every maneuver short of firing the descent engine for the descent to the lunar surface.

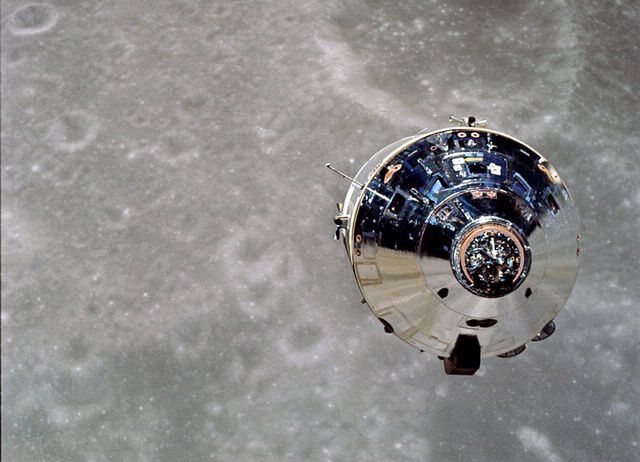

The Apollo 10 Command Module, “Charlie Brown,” as seen from the detached Lunar Module, “Snoopy.” (NASA)

What did they learn on this mission? Was there anything that surprised them, or that they were glad they figured out on this dress rehearsal mission?

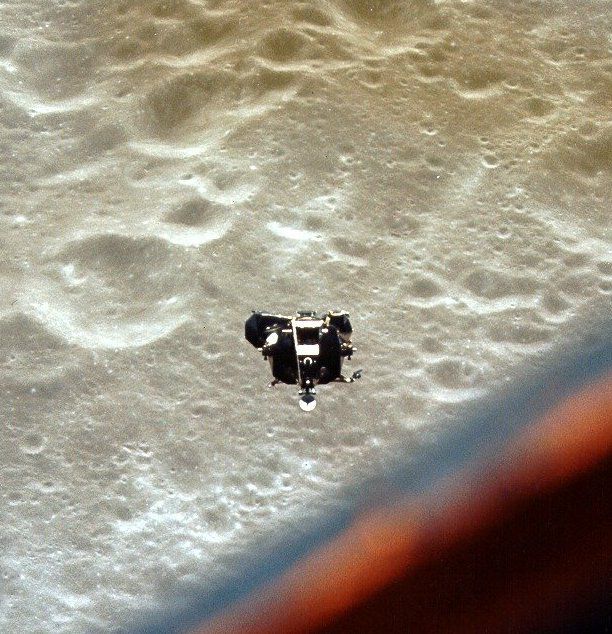

There was a problem at the point. Stafford and Cernan descended, ultimately, to 47,000 feet. Then they were to reorient the spacecraft, and carry out, essentially, a practice of aborting descent, and fire the ascent stage to put themselves back on a trajectory to rendezvous with the Command and Service modules.

Something went wrong. Their switch settings were wrong. The crew made a mistake and the lunar module went on a wild gyration, rolling around and flipping around, and it was a dangerous moment. Stafford regained control, but that was kind of a scary moment. You could hear—and I heard it watching on TV—Eugene Cernan say, “son of a bitch.” Some religious groups complained of bad language on the radio.

Stafford had to manually bring it back onto the correct attitude. This took place after the ignition of the ascent engine. They were certainly out of control there for a couple seconds until Stafford got it pointed back in the right direction for ascent.

It sounds like it was a pretty close call, and they could have crashed into the moon. What would the impact on the Apollo program have been if Apollo 10 ended in such a catastrophic failure?

It would have been a huge setback. The first thing would have been to figure out what the hell happened. I guess they would have had audio from the crew as they struggled to try to regain control.

Any failure, on any of those missions, 8, 9 or 10, especially a fatal one, would have dramatically set back the moon landing. Apollo 11 would not have been the moon landing mission. I think the scenario you would be likely to see, especially if the crew was lost, would be a long delay. Then Apollo 11 would have flown the practice mission over again, and Apollo 12 would have been the landing. Whether that could’ve been done in 1969 is a totally speculative.

But the thing is that this was, all in all, except for this one incident, a totally successful mission. The overall lesson of Apollo 10 was: Everything’s ready to go.

Did they think at all about landing during Apollo 10? Was that ever on the drawing board, or was it never even a consideration?

I’m sure astronauts and others talked about it. I remember at the time the media talked about it. Apparently, the LM was too heavy, and they hadn’t fully fueled the ascent stage. The New York Times story that just ran about Apollo 10 says Cernan thought maybe they intentionally didn’t give them enough ascent propellant, so that they couldn’t even contemplate landing on the moon.

But given how dependent they were on ground control, it’s just really hard to see how they could ever possibly have just said, “Oh, we’re going to do it anyway,” and landed on the moon. It might’ve been possible to land on Apollo 10, but at the time, NASA had done very few missions. If NASA was not so strongly motivated by the 1969 goal, the challenge from John F. Kennedy, it might have done extra practice missions. As far as Houston and the NASA leadership were concerned, they did essentially the minimum number of missions that they could imagine to get to a lunar landing.

The ascent stage of the Apollo 10 lunar module coming in to dock with the command module, after having descended to 47,000 feet above the surface and jettisoning the descent stage. (NASA)

It is commonly said that Apollo 10 holds a few significant records. One is that, given the position of the moon during the mission, the Apollo 10 crew has been farther away from Earth than any other humans. And the other is that during their return to Earth they went faster than any other humans in a vehicle. Do you know if those are official records?

I’ve heard that, and the two make sense together. If the moon was at apogee, its most distant point from Earth, during that mission, then the crew would have flown farther away than any other missions. And if the moon was at apogee, the fall back to Earth would have been a little bit faster, a couple hundred miles an hour.

Two of the crew members on Apollo 10 actually ended up going back and walking on the moon, John Young and Eugene Cernan on Apollo 16 and 17, respectively. How many people have flown to the moon twice?

It’s a very select group. There are actually three people who went to the moon twice. Jim Lovell was the other one, on Apollo 8 and 13, but of course his landing was canceled on 13. So, just those three guys, and it’s a very select club already. There are only 24 astronauts who went to the moon, 12 of them walked, and only 3 went back to the moon twice. And Young and Cernan are the only two who orbited and landed.

They were very good and competent astronauts; that’s why they were picked as commanders. But they also were lucky.

The Apollo program at large, of course, involves so many different factors, so many different missions going back through the legacies of Gemini and Mercury. How does Apollo 10 fit into that big picture?

Apollo 10 was the mission that proved that the system was ready to land on the moon. It made Apollo 11 possible. It demonstrated that the command and service modules, the tracking system, the mission control, was ready to attempt a landing. So, it made possible Apollo 11’s landing on the moon.

This post by Associate Web Editor Jay Bennet was originally published by Smithsonian.com.

Copyright 2019 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 17 July 2019

-

Categories:

Air and Space Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture , Science and Nature