Weaving family histories when threads have been broken

Genealogist Hollis Gentry talks about her work rediscovering connections that have been lost to history.

“We are a lot more alike than we are unalike. We have more similarities than differences. When you start going back in the records you find that every family has suffered all kinds of triumphs and tragedies, births and deaths, we all go through the same thing.”

Spit in a vial and mail it off for DNA analysis to a company such as Ancestry.com or 23andMe and in a few weeks you will likely be linked electronically to hundreds of uncles, aunts, cousins and other relatives you may never have realized existed. This is one of the exciting (and slightly alarming) new miracles of modern medical science.

At the Smithsonian Institution Libraries branch of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the genealogical connections Hollis Gentry helps turn up take a bit more time and work to establish. Tracing the histories of people who may exist only as cryptic names and statistics in centuries-old record books and ledgers is as exciting as for Gentry as turning up a long-lost relative through DNA.

Hollis Gentry in her office at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. (Photo by John Barrat)

“Genealogy is a journey of self-discovery. I love the challenges, I love the mystery of it,” she says. Drawn to genealogy as a kid, “I’ve worked in the field for about 30 years now,” she adds. “I’ve been a professional genealogist, I’ve worked in special libraries, I’ve also worked for a lineage society, and prior to coming to the African American History and Culture Museum, I worked for the Daughters of the American Revolution as a genealogist on their staff.”

Gentry recently found some time to talk with Torch writer John Barrat about her work.

What is your role as a genealogy specialist at Smithsonian Libraries?

What distinguishes me from other Smithsonian Libraries’ staff is that I really do focus on genealogical research, helping Smithsonian staff, visitors and patrons gain access to internal genealogical resources held by the Smithsonian. I provide an additional level of research services to Smithsonian curatorial staff.

From SI staff, most of the questions I get relate to how to access these databases and what do we have here? It may be someone working on biographical projects who needs another layer of assistance. They might be looking for the parents of someone or the descendants of someone. Depending on the nature of the question, if it is from a Smithsonian staff member, I will guide her or him to resources within the Smithsonian.

If it is someone external to the Institution then I try to refer them to another institution where I think they will probably get the assistance they need. Sometimes, it is simply a matter of me taking 5 minutes to quickly find something and send them to that resource.

What external resources are you referring to?

It depends. A lot of queries relate to using the database Ancestry.com which has thousands of genealogy and biography databases and resources. I might send them to Family Search, a non-profit organization that collects resources globally, or I might send them to a state archive or a local library or a genealogy library.

With digitization there are many directions one can go today. It’s amazing because so much has been digitized. It used to be we would refer someone to a brick and mortar research Institution. Now, it’s a matter of telling them “Go to this webpage and if you live close enough you can visit in person.” If not, we can send a link to a contact who works there so that they can further pursue that research.

The big shift in genealogy is that a lot of material and content is online, so it is a matter of sending people to Web pages or to actual content, say a link to an actual book on Google Books.

Is genealogy more of a focus at the African American History and Culture Museum than other SI museums?

Yes, we have space dedicated to a genealogy research experience. We are developing within the Library a reference collection of genealogical guides and “How To” books. We are also going to have a presence online of reference materials that identify some of the key institutions and resources one can access.

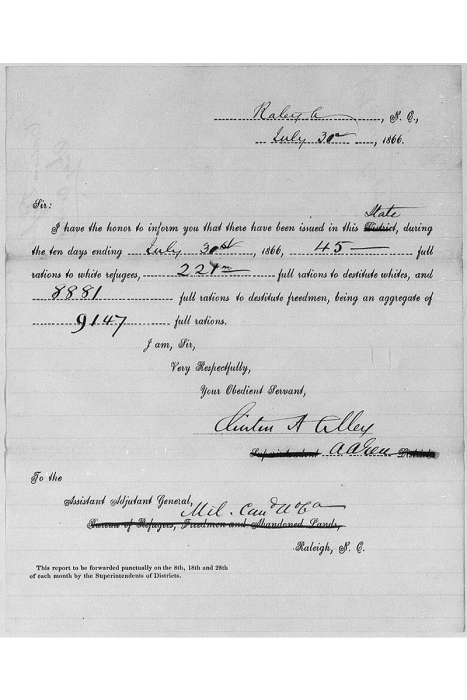

One of our major projects here is the Freedman’s Bureau Records. This was a post-Civil-War federal agency that has an archives with a little over 2 million records collected by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands that was established in 1865 to help former slaves and refugee whites in former Confederate states rebuild their communities. The records are bureaucratic but they contain a lot of genealogical information, so African American History Museum Director Lonnie Bunch decided the museum would sponsor this project to assist African Americans with their genealogical research.

The United States Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was created by Congress in 1865 to assist in the political and social reconstruction of post-war Southern states and to help formerly enslaved people make the transition from slavery to freedom and citizenship. In the process, the Bureau created millions of records that contain the names of hundreds of thousands of formerly enslaved individuals and Southern white refugees. This is a report of rations given to freedmen and poor whites, Raleigh, North Carolina, July 30th, 1866.

The Freedman’s Bureau Records were selected because they were created during a period when formerly enslaved people were emerging in public records. With genealogical research we work from the present and the known and into the past. This era is where many researchers have difficulty tracing further back. The Freedman’s Bureau is at a major crux in the historical record of a wealth of documents that have the potential to help those trying to go further back in the antebellum period and document their ancestry.

What’s really rare about these records is they are recording people in the midst of transition, in the midst of upheaval, this is a post-war era where communities have been destroyed, people are being forced to move for military reasons, whatever reasons, some homes have been destroyed, and the federal government sent in relief. They established temporary villages and temporary shelters, and in the course of doing that work they are recording names, they are recording details about individuals. This is highly valuable information that is useful to genealogists. They were being recorded for other reasons, but there is a wealth of details in those records.

In typical genealogical research we consult a variety of types of records from personal family papers to local papers, let’s say in the community local government town records, then you get to county records, state level records then federal records, then you have some private institutional records. These are all the types of resources we consult.

What happens with the Freedman’s Bureau, as an example, is that its records connect to some of these other public and private records. Some of the men and women who were working for the Freedman’s Bureau were actually functioning previously in some capacity, say as the clerk of a court, and may have been hired by the Freedman’s Bureau to temporarily to assist with its work. So they already had some record keeping skills.

Others were just simply given directives like “we want you to identify all the people in the community,” so they created these records, but they are similar to what could have been collected by the local government, so they parallel what one would typically find outside of the federal government. That’s what’s really unique about it we have the ability to connect some of these other sources to the Freedman’s Bureau records.

Were genealogical records of enslaved African Americans kept by their owners?

It’s a mixed bag. This is one reason it is exciting to be living now. There are so many digital projects we are unearthing, records that have been in archives for a very long time that no one has paid attention to. Some slave-owning families kept meticulous records. Jefferson was one example.

Often, it depended on the type of slave owning. Some slave owners who had a large number of properties enslaved very large populations. They had different managerial skills. Some were good record keepers, some were not. In some instances we don’t know because the Civil War intervened and records were destroyed.

In looking at African American records from the 17th century up until today, the status of the individual often determined what types of records were created. Records of slaves on ships are classified as slave records but there were plenty of African Americans here who were not enslaved so they appear in records of that time period in different ways. If there were laws that required that African Americans be recorded separately, you will see in segregated records “black people,” “colored people,” “Negro,” or however they were described at the time. In other areas no distinction was made.

As slavery expanded so did its laws and restrictions. So, it is surprising that there were a lot of African American enslaved people who were well documented because they were treated as property. But they were documented in the context of being the property of somebody else. So, the research challenge is to be aware of that and try and figure out how did the record keeper regard this individual and then what were the laws and the rules for recording them, how were they going to be described? Trying to figure that out helps you to identify those records.

What’s happening now is historians are finding a boatload of documentation on African Americans. The challenge is in trying to figure out how to characterize them, how to distinguish them, depending on how they appear in records. For example, at one point enslaved people were not recorded as having surnames. But then there are plenty of instances when enslaved people did have surnames and they were recognized by the people who enslaved them. That’s what I mean when I say it’s a mixed bag.

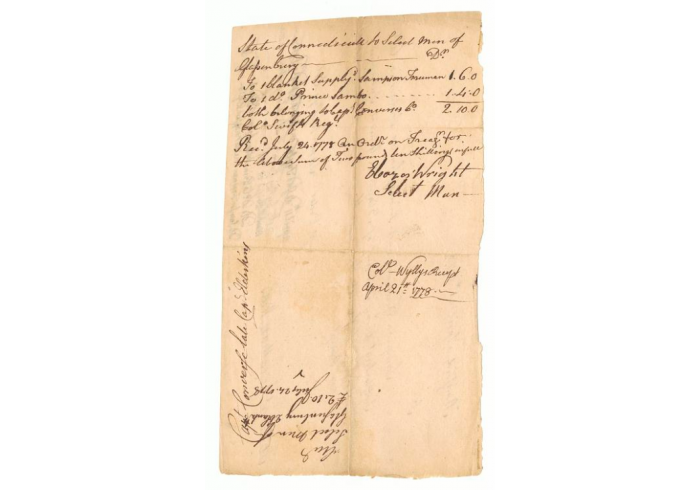

Receipt for blankets given to African American Revolutionary War soldiers Prince Simbo (ca. 1737 – 1810) and Sampson Freeman, April 21, 1778. (National Museum of African American History and Culture)

And this is where you come in…

Yes. I am very familiar with all of these records—the antebellum period that predates to a certain extent the Freedman’s Bureau that was formed in 1865, so this is post-Civil War Era when those records were created. The records created prior to that are government records, local town records or private papers. In my role here I try to find a way to connect them.

It’s not a very easy job to do. As a genealogist at the Daughters of the American Revolution I had to become familiar with records across a broad spectrum of types of documentation across the nation from the Revolutionary era from the late 18th century on up to the 21st century. Now, I am taking that knowledge and those skills and applying them here at the Smithsonian. I am identifying the resources that the Smithsonian has that can be applied to genealogical research.

One aspect of this is that it is all new. I am the first genealogist for the Institution and as such, I am sort of creating it as I go. Fortunately, because I was here previously, I am familiar with the Institution. The exciting part is that there are so many new initiatives the Institution is supporting. It’s a matter of trying to conceptualize all of it and see where I can plug in.

For example, I want to have tutorials and online resources and we have the Learning Lab, which is going to provide an outlet in a different area. We have the Smithsonian Libraries which is going to have the Freeman’s Bureau Database online, I want to look at how the online archives will help or the transcription center. It’s a major challenge.

I try to assist people as they seek to outline their identity. Some athletes practice all the time. I research all the time, morning, noon and night. Sometimes I wake up at 4 in the morning with an idea or answer to something that I had read or heard about the previous day. Sometimes, if I am suffering from insomnia I will go online and try to clear out my e-mail and then I will see something of interest and I will find something. In the genealogy community we laugh about the 4 a.m. epiphanies.

Researching the family histories of many Americans, particularly African Americans, is difficult because of the lack of records. (Photo by John Barrat)

Do you have any suggestions about a broader focus on genealogy at the Smithsonian?

I think the Institution needs a Genealogy Center that works in tandem with all of its museums, all of its curators, and all of its researchers, because everyone has different research projects and challenges. In my position I focus on African Americans, but also genealogy in general. I think the Institution needs a number of genealogists who are specialists in different ethnicities, nationalities, and international resources. We are a nation of immigrants with all sorts of different traditions, record keeping practices, histories, everything.

It would be great if the Institution could support an international genealogy center. That’s my fantasy. The Arts and Industries Building might be a great location for meetings, conferences and training.

Part of what I am doing now is looking at social history and anthropological studies, how they are looking at kinship, how it is preserved in different cultures, it’s really fascinating, This being an institution with an international face, I think it would be really great if we could have genealogists of all sorts coming here and working.

One of the major things I learned when I worked for the Daughters of the American Revolution is how connected and how similar all our histories are. Everyone at some point reaches that juncture in their family history that is blank, it’s the unknown, everyone has a brick wall, and everyone has an ancestor who moved from one place to another. We have all sorts of dramas and histories in our families. We are a lot more alike than we are unalike. We have more similarities than differences.

When you start going back in the records you find that every family has suffered all kinds of triumphs and tragedies, births and deaths, we all go through the same thing, what makes it fascinating is how each group relates to those challenges and triumphs, how they preserve it, what they do with that information, and some of the relationships that are formed.

Posted: 13 August 2019