“A powerful place of healing and comfort”

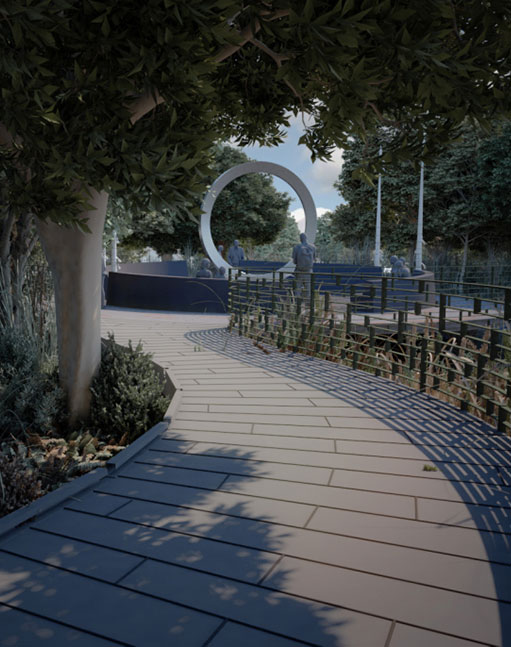

After years of planning, groundbreaking for the National Native American Veterans Memorial took place Saturday, September 21. When it is unveiled on Veteran’s Day, November 11, 2020, four tall metal lances will adorn the memorial, which will stand on the east side of the National Museum of the American Indian. Metal loops welded to the base of each lance will hold prayer cloths tied on by visitors. Each time a breeze lifts a cloth “that’s a prayer sent out to your veteran,” says Harvey Pratt (Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma), the memorial’s designer.

Design by Harvey Pratt/Butzer Architects and Urbanism, illustration by Skyline Ink, courtesy of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Other elements of the memorial will be a large, elevated stainless steel circle balanced on a carved stone drum form, continuously flowing water, a flame to be lit on ceremonial occasions, benches for gathering and reflection and a medallion from each branch of the armed forces of the United States.

“It will be a powerful place of healing and comfort,” Pratt observes.

One hundred and twenty-plus artists and architects submitted proposals for the design of the memorial. Ultimately, the competition’s jurors chose the work of Harvey Pratt, whose professional career included years working as a forensic artist for the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation. Pratt was a pioneer in soft tissue reconstruction of the face, skull reconstruction, fugitive age progression and age progression of missing persons and his work helped solve many criminal cases.

Harvey Pratt, the designer whose concept was selected to create the Smithsonian’s National Native American Veterans Memorial for the National Museum of the American Indian is a Cheyenne and Arapaho tribal member. He is a self-taught artist from Oklahoma and a forensic artist. Pratt works in oil, watercolor, metal, clay and wood. His works include themes of Native American history and tradition and the Cheyenne people.

Photo by Neil Chapman, courtesy of Harvey Pratt

“I love doing forensic art,” Pratt said during a design presentation after he was chosen as one of five finalists in the memorial competition. “I’ve done work all over the United States in forensic art. I’ve identified lots of unidentified human remains and drawn many witness description drawings. That was my specialty and I enjoyed being a law enforcement officer helping people.”

Pratt also served as a Marine in Vietnam. “I always wanted to be a veteran,” he says, because growing up he saw “our people treated us [veterans] different, like we were something special. As children we had to go to dances when veterans came home. They would have a dance for them and a give-away and they would give them a song and they would honor them. And so that was instilled in me when I was a little boy.”

Harvey Pratt in DaNang, Vietnam. (Photo by R.D. Pratt, courtesy Harvey Pratt)

Few outside the military and American Indian Nations know that Native people have served in the U.S. armed forces since the American Revolution and continue to serve today. Native Americans serve at a higher rate per capita than any other population group.

The nation’s capital is known for its grand monuments and solemn memorials, including many honoring the nation’s veterans. Yet no national landmark in Washington, D.C., focuses on the contributions of American Indians, Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians who have served in the military since colonial times.

Ely S. Parker, 1860–65. At the surrender at Appomattox in 1865, Ely S. Parker (Seneca, 1828–1895) was the highest ranking American Indian in the Union Army, a lieutenant colonel. As General Ulysses S. Grant’s secretary, he drafted the terms of surrender. General Lee, noticing that Parker was an American Indian, remarked, “I am glad to see one real American here.” Parker later recalled, “I shook his hand and said, ‘We are all Americans.’” Photo by Mathew Brady. National Archives and Records Administration 529376

Commissioned by Congress in 1994, the National Native American Veterans Memorial was to be constructed on the grounds of the National Museum of the American Indian in the heart of Washington, D.C.

Creating such a memorial was not a responsibility the American Indian Museum took lightly. Rebecca Trautmann, the memorial’s curator and other NMAI staff launched the effort five years ago by creating a committee of Native American veterans and family members to advise the museum on the project. Next, they organized and a series of 35 consultations with veterans, tribal leaders and family members in Native communities across the United States and in Alaska and Hawaii.

“We wanted a better understanding of the experiences of Native Veterans who served in the military. We listened to what they wanted to see in a memorial, what stories they wanted it to tell and what they thought the experience of visiting it should be. Those findings made up the set of design principles that formed the basis of the memorial’s design competition,” Trautmann says.

One of the biggest challenges was finding a design that would be meaningful to native veterans from so many different traditions, including Alaskan native and native Hawaiian, yet not become so abstract that it wasn’t meaningful at all, Trautmann adds. “I think Harvey Pratt’s design really accomplishes that, as it is based on a circle, a form that is meaningful in a lot of different traditions: the shape of the sun, the moon, plant stalks, it brings to mind things like storytelling circles, the cycle of life, the cyclical nature of time… It’s a theme that really connects with a lot of communities and traditions.”

Arapaho Projects Manager Lena Nells of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Language and Culture Program and Vice Commander Raymond Baker of the Southern Ute Veterans Association at the groundbreaking ceremony for the National Native American Veterans Memorial in Washington,D.C., on September 21, 2019.(Photo by Jourdan Bennett-Begaye)

“Our consultations also revealed that people wanted spirituality to be an important element of the memorial,” Trautmann says. “They wanted the experience of visiting it to be a healing one, whether for veterans who served decades ago, for family members remembering other family members who served, or for young service members just returning home. Healing was to be an important part of it.”

This aspect of the memorial also played a part in its placement on the northeast side of the museum. “The veterans and family members that we spoke with really wanted it to be on the quieter side of the museum rather than say, facing Independence Avenue, where there is so much more traffic and noise, cars and buses,” Trautmann says. “Also the proximity to water and the connection of water to life was a significant consideration. Our River Walk and Wetlands areas are both on the north side of the NMAI building.”

“We do anticipate large numbers of people coming to visit,” Trautmann adds. “So many of the communities we spoke with in our consultations are planning honor flights to bring their veterans here for the dedication in particular, but at later dates too. We know it going to be heavily visited. We’re thinking how we will best manage that.”

The National Native American Veterans Memorial, view from the pathway. Design by Harvey Pratt/Butzer Architects and Urbanism, illustration by Skyline Ink, courtesy of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Watch video of the ceremony from NBC4 Washington at blob:https://www.nbcwashington.com/ecb8a486-412d-48fe-836a-20d659409bdf

Posted: 23 September 2019

-

Categories:

American Indian Museum , Collaboration , Feature Stories , History and Culture , News & Announcements

Thank you for an excellent and important article!

Please check detail of Ely Parker’s rank. See references to him as a COLONEL, then as a Brevet Brig. General of Volunteers, and later as a US Army Brig. Gen. If correct he should get full credit!