Just say No (way): How Prohibition changed the American wine industry

In celebration of the end of Prohibition on this day in 1933, we’re raising a glass and making a toast to the triumph of vigorous viticulture.

Congress passed the National Prohibition Act in January 1919, and a year later, Americans were barred from making, transporting, selling, exporting, and importing intoxicating liquors. Prohibition snarled industries, expanded crime, and upended social life. Yet in nearly 13 years as the law of the land, Prohibition failed to convert the United States to a nation of teetotalers.

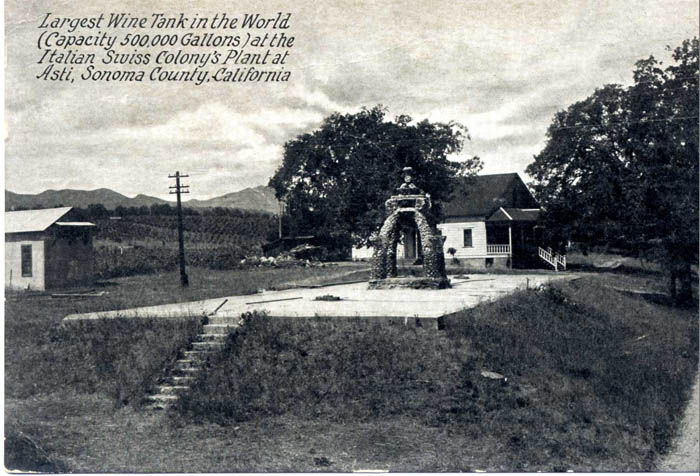

To understand the impact of Prohibition on American wine, it’s helpful to start with a sense of the industry at the time. By 1919 grape growing and winemaking were successful commercial enterprises in several states. California was the lead producer of table wines, with about 700 bonded wineries (businesses that made and stored wine under a bond that guaranteed payment of federal taxes). Some of these were family owned and had been established in the 19th century. Others were larger enterprises such as the Italian Vineyard Company and the Italian Swiss Colony, both in California.

Postcard, around 1910s. American Food History Reference Files, Division of Work and Industry. National Museum of American History

American wine during Prohibition was not a simple narrative of unemployed vintners and defunct wineries. That happened, to be sure, and the loss of winemaking know-how, technical skill, and professional equipment took years to regain. But there were also many exceptions and entrepreneurial workarounds that kept elements of the industry viable during the dry years.

Ad, 1880s. Prohibition was the second disaster that befell the Gundlach family’s wine business. The 1906 earthquake and fire in San Francisco destroyed the wine vaults. American Food History Reference Files, Division of Work and Industry, National Museum of American History.

Due to exceptions in the law allowing for the production of wine for sacramental and medicinal purposes, some winemakers were allowed to stay in business. Calling itself “The House of Altar Wines” during Prohibition, Beaulieu Vineyard obtained government permits to produce wine, shipping it inside barrels marked “FLOUR,” to discourage pilferage during transit.

The Concannon family, whose vineyard ownership in the Livermore Valley stretched back to 1883, received official permits to make and sell wine during Prohibition. In 2014 they donated a few bottles from the 1920s. This 1929 bottle of sherry includes permit information: “Bonded Winery 616 / 11th Permissive Dist. Calif. / Permit Calif. A 854.”

Home winemakers provided another market for grape growers. Indeed, grape production increased exponentially, due to the law’s provision that allowed the sale of wine grapes to male heads of households to “preserve fruit” through fermentation. Patriarchs were permitted to produce up to 200 gallons of wine per year. With home winemaking on the rise, grape prices soared in the early 1920s and acreage planted in wine grapes increased. One industry source estimated that between 1920 and 1933 about $100 million of new money was invested in vineyards. In California, vineyards expanded from about 300,000 acres in 1920 to 577,000 by 1927.

Home winemaking equipment used by an Italian immigrant family in New Jersey in the early 20th century.

Although more grapes were planted, in winemaking all grapes are not created equal. The favored grapes for home winemaking during Prohibition were not the so-called noble varieties—Cabernet, Pinot Noir, etc. Instead, new vineyards were planted in grapes that were especially suited to survive shipment to eastern cities, where communities with large immigrant populations maintained their customary practices of enjoying wine with everyday meals and as part of celebrations. In 1920 more than 26,000 railcars of grapes made the trip from California, and by 1927 that number reached over 72,000. The railroads saw the potential in this booming market and set up grape distribution sites in cities such as Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Philadelphia.

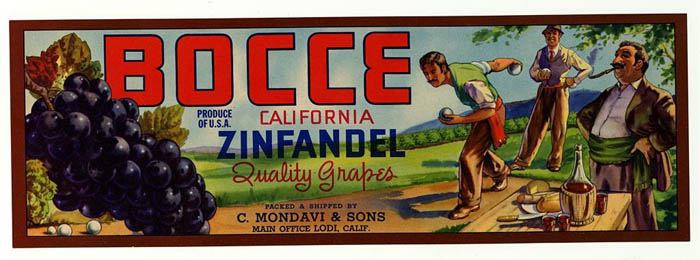

Red grapes were popular because they could survive the transcontinental journey, but also because it was easier to make a drinkable red than a stable, drinkable white. White grapes were ripped out of vineyards to make room for the moneymakers—the red varieties like Alicante Bouschet and Zinfandel that produced deeply hued red wines. These varieties were also known as “black grapes” because of their dark color.

A label for “black grapes.” The imagery used on grape crate labels played on ethnic stereotypes, which was common on other fruit and vegetable labels from the period. (National Museum of American History)

Entrepreneurs seized opportunities to capitalize on the grape loophole, some leaving other employment to get into the trade. One such visionary was Cesare Mondavi, an immigrant from Italy, who in 1906 had settled with his wife on the Iron Range of Minnesota among a community of Italian miners. By 1919 the Mondavis had four children, and Cesare had left the mines to run a store. At Prohibition, his Italian neighbors designated him their representative to travel to California in search of grapes they could use to make wine at home.

On his first trip, Mondavi discovered that California was nothing like northern Minnesota. Within three years he moved his family to Lodi, in the Central Valley, and from there he began buying grapes wholesale and shipping them to customers across the country. Such was the beginning of what became one of California’s most innovative and storied winemaking families.

Grape crate label reflecting the Mondavi family’s Italian heritage, including red wine, bocce, and family. (National Museum of American History)

The vigorous expansion of viticulture under Prohibition did not last. The almost frenetic, high-pressure development of vineyards had, by 1926, produced a supply greater than demand, and prices crashed. The price per ton of California grapes was about $60 in 1926; in 1928 it had fallen to $17.

Knowing this, it’s hard to reconcile choices made by another Italian immigrant family, the Pedroncellis, of Sonoma’s Dry Creek Valley. John and Jim Pedroncelli explained how their father bought a vineyard in 1927, entering the grape trade amidst the glut and falling prices. The Pedroncellis believe that for their father, an immigrant and war veteran, investing in wine grapes during Prohibition was a business decision that carried manageable risk, primarily because the property was located in a community of other Italian Americans where mutual support was the norm. The Pedroncellis also noted that the property contained some very old Zinfandel vines that were still productive. From these vines on the steep hillside near Geyserville, the Pedroncellis replanted their vineyards, grafting buds from those old vines—the Mother Clone—onto healthy rootstock. The new vines became the foundation for their successful winery in the decades that followed.

John (Giovanni) Pedroncelli and his son John Jr. with the “Mother Clone” zinfandel, 1950s. Courtesy of the Pedroncelli family.

Repeal of Prohibition was widely anticipated and supported by most Americans. As the movement gained momentum, winemakers and growers prepared to restart the industry—but it wouldn’t be easy. When repeal finally came, on December 5, 1933, a majority of American wineries had either gone out of business, collapsed into decay, or been repurposed. Nationally, the number of bonded wineries had slipped to 268 and, although many were eventually revived, significant damage had been done: cooperage had dried out, machinery had become dated, legitimate distribution channels and markets had withered. What’s more, acres and acres of “lesser” grape varieties had to be removed and replanted with the higher-value grapes preferred for making table wine. The story of how American winemaking was reimagined and rebuilt in the decades following repeal is continued in the museum’s exhibition FOOD: Transforming the American Table.

This post by Paula J. Johnson, curator in the Division of Work and Industry at the National Museum of American History, was originally published by the museum’s blog, O Say Can You See?

Bonus!

Warren Winiarski Receives James Smithson Bicentennial Medal

Winemaker Recognized for Dedication to Winemaking and Land Preservation Lead Supporter of Smithsonian Food History Programs for a Quarter Century. More on Newsdesk.

A pioneering California winemaker gets his due from the Smithsonian

It all started with a phone call, in 1994 or thereabouts. Warren Winiarski, founder of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars in Napa Valley, dialed up the main switchboard of the Smithsonian Institution, in the era before websites and email, and asked the nonplussed operator what the nation’s museum was planning to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the 1976 Judgment of Paris wine tasting, where California wines beat the best of France. More from the Washington Post.

Posted: 5 December 2019