Slavery and the Smithsonian

On this date in 1865, the 13th amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery was ratified by the states. The complex legacy of slavery will always be part of our history; many of our most treasured institutions were built, quite literally, by enslaved people. John Barrat reexamines a question that has never been resolved by scholars. Was the iconic Smithsonian Castle built by slaves?

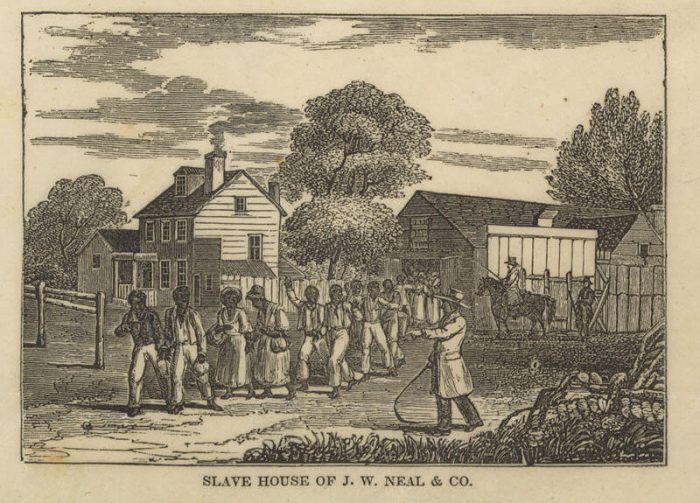

The title page of an abolitionist tract which stresses that [a] slave coffle marching by the capital is not fancy, but a fact not unfrequently occurring; the tract cites a few eyewitness descriptions.

Source: Slavery and the slave trade at the nation’s capital (New York,1846). (Copy in Library Company of Philadelphia)

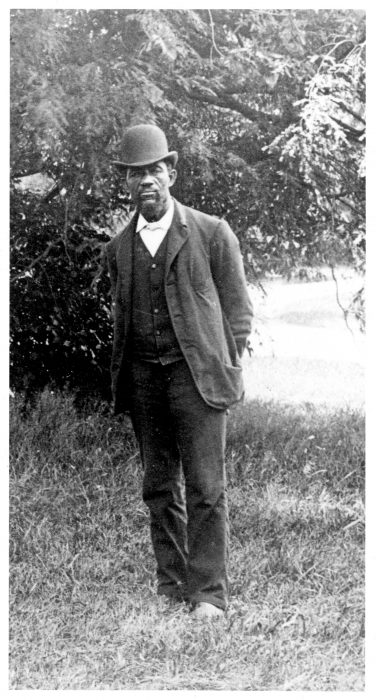

In 1852, Solomon G. Brown, a free black man living in Washington, D.C., was hired to work as a paid employee of the young Smithsonian Institution by Secretary Joseph Henry. But even as a free man, Brown had reason to fear D.C.’s slave merchants, who were not above kidnapping free persons of color and selling them into slavery, according to an essay by anthropologist and historian Mark Auslander that appeared in the journal Southern Spaces in December 2012.

In 1852, Solomon G. Brown was hired as the Smithsonian Institution’s first African American employee. Brown worked for 54 years at the Smithsonian, fulfilling many duties under secretaries Joseph Henry, Spencer Fullerton Baird, and Samuel P Langley. Brown formed a very close bond with Baird, becoming his “eyes and ears” when Baird was out of town. He was also a naturalist, poet, illustrator, and lecturer. Although he had no formal education, Brown was known by many as Professor Brown. (Photographer unknown, circa 1852)

“On July 21, 1858, six years after he began work at the Smithsonian,” Auslander writes, “Brown took the precautionary step of obtaining a certificate of freedom, in which his white friend and former employer at the Post Office, Lambert Tree, swore in front of a Justice of the Peace that Brown had always been free.” Such a document might save Brown from a lifetime of slavery should he be kidnapped by slave traders.

Image of the Smithsonian Institution Building or Castle from the 1860s, probably taken by Mathew Brady’s Studio. There are several versions of this picture from slightly different angles and the picture is held by the Smithsonian Institution, the Library of Congress, and the National Archives, among other repositories. In one of our two copies, there is a beautifully written caption, “Washington, D.C., April, 1865.” The US Capitol is in the distance, with downtown Washington behind the Castle.

From 1847 to 1855, during the years that the iconic Smithsonian “Castle” was being built, a notorious slave pen known as the Williams House or Yellow House was doing a prosperous business just a few steps away. It was located directly across Independence Avenue (known then as “B” street) from where the Hirshhorn Museum now stands, Auslander writes. There, people of color, “many of them kidnapped or arrested on the flimsiest of pretexts, were held under horrid conditions pending their sale to points south.” The equally notorious Robey Tavern and Slave Pen was operating just down the street at 7th and Maryland Avenue.

The Smithsonian Institution Building (SIB) seen from downtown Washington, D.C., from across The Mall, around 1855. In the foreground are construction materials along 15th Street, NW for the new wing added in 1855 to the Treasury Building. The Treasury building is the oldest departmental building in Washington, D.C.having been completed in 1842 and expanded three times by 1869. This area was also known in the 1860s as the red light district called Murder Bay. The canal bordering the Mall before being converted to form Constitution Avenue is the sliver at right center. The white residence at the far left is at the corner of 15th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW.

The prominence of slavery in Washington, D.C. during the period the Smithsonian Institution Building was being constructed has led many people to question if slave labor was used to build it. After all, it is well established that enslaved laborers worked to help put up two other well-known federal buildings in Washington—the White House and the U.S. Capitol.

A slave coffle in Washington, D.C., possibly marching to auction, from William S. Dorr, Slave market of America, published by the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1836. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-19705. The J. W. Neal slave house was near the city’s center market.

“Did slaves help build the Smithsonian Castle?” is a question that Rick Stamm, Keeper of the Castle in the Smithsonian Office of Architectural History and Historic Preservation, has been asked repeatedly during his 25-year tenure. “It is entirely possible,” Stamm says, “but there is no actual evidence. There is a lot of speculation. It’s another Smithsonian mystery.”

Fifteen quarries from across the Mid-Atlantic bid on the Smithsonian Castle project in 1846, and the Castle could have ended up any number of different colors: granite, marble, white or yellow sandstone. The owner of the Seneca redstone quarry, 30 miles away in Maryland along the Potomac river, underbid the competition and the red sandstone façade of the Smithsonian Castle makes it one of the most striking buildings in Washington.

Workers in the Seneca Quarry, c. 1890. Photo courtesy of Garrett Peck

In the 2013 book The Smithsonian Castle and the Seneca Quarry, author Garrett Peck makes clear that the Seneca red sandstone used to build the Castle was quarried with the help of slaves who were the property of the quarry owner.

According to Stamm, Gilbert Cameron, general contractor for the Castle, purchased the sandstone from Seneca quarry, but did not himself own slaves, according to the Washington, D.C. Slave Owner Petitions 1862-1863, “I also have checked the 1850 and 1860 U.S. Federal Census Slave Schedules with the same negative result,” Stamm adds.

“I’ve looked for 40-plus years for evidence that the Smithsonian hired slaves, especially in the construction of the Castle, but have never found any,” says Pamela Henson, an historian at the Smithsonian Institution Archives. “It’s entirely possible, but there is no actual evidence.”

The Washington, D.C.-based photographer Andrew Gardner added hand-tinted flames to this albumen print, giving an impression of the fire that raged January 24, 1865. Smithsonian Institution Archives Neg. No. SIA2013-08351

A fire in the Castle in 1865 destroyed a lot of the Smithsonian’s early records, which may have contained documentation indicating slaves helped excavate the foundation, pour the concrete, set the foundation stones and build the Castle, but “there’s no proof we’ve ever found,” Henson says. “But it is possible there were records that went up in flames.”

“Joseph Henry had complex racial attitudes,” Henson adds. “He absolutely believed African Americans were mentally and physically inferior to Caucasians, and actively supported re-colonization efforts. He believed, if freed, [African Americans] would become extinct in northern climates. But he also hated the practice of slavery and felt it degraded the owners as well as the slaves.”

There is a growing movement by many U.S. colleges and universities, to address the issue of slave ownership and its legacy with historical investigations, outreach, symposiums, and in some cases, reparations. Will we ever know for certain whether enslaved people help build the Smithsonian?

“It’s always possible that new information hidden away somewhere might reveal more than what we know now,” Stamm says.

Posted: 6 December 2019

-

Categories:

Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , History and Culture