Lessons in community: The time to be accountable is now

Secretary Bunch commemorates two women whose advice and pioneering work at the Smithsonian have guided him through every position he has held at the Institution. This month, Louise Daniel Hutchinson and Zora Martin Felton remind us that the Smithsonian is at our best when we are community driven; when we strive to respond to the needs of the audiences we serve; and when we value stories and contributions from every hand.

In April of 1968, as news of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. spread, Washington, D.C., erupted into four days of riots. From U St. to Capitol Hill, Shaw to Anacostia, the city roared, leaving 13 dead and thousands injured by fires, police, and rioters. The assassination and upheaval galvanized Louise Daniel Hutchinson. A Southeast D.C. resident and Howard University graduate, Hutchinson had studied sociology and history under renowned African American scholars E. Franklin Frazier and John Hope Franklin. As Hutchinson would recall in an interview with Smithsonian Institution Archives decades later, she realized in that moment, “now is the time when you’ve got to be accountable, when you’ve got to hopefully do something that makes a difference.”

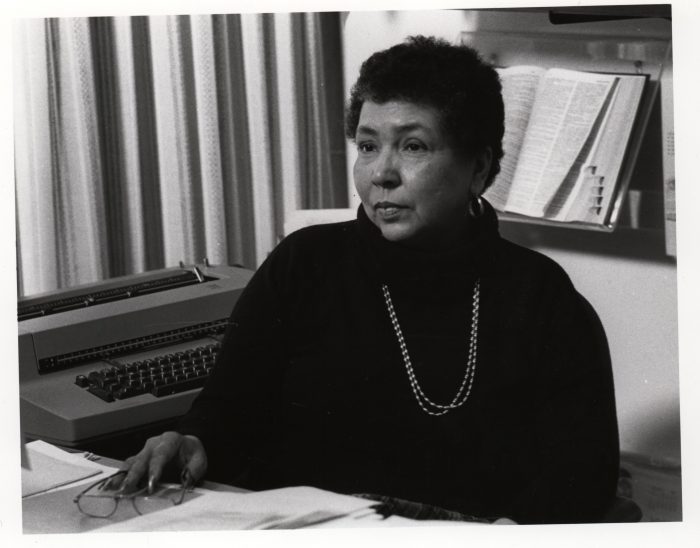

Louise Daniel Hutchinson, seated in her office at what is now the Anacostia Community Museum in 1983. (Photo by Chris Capilongo, as featured in The Torch, October 1983)

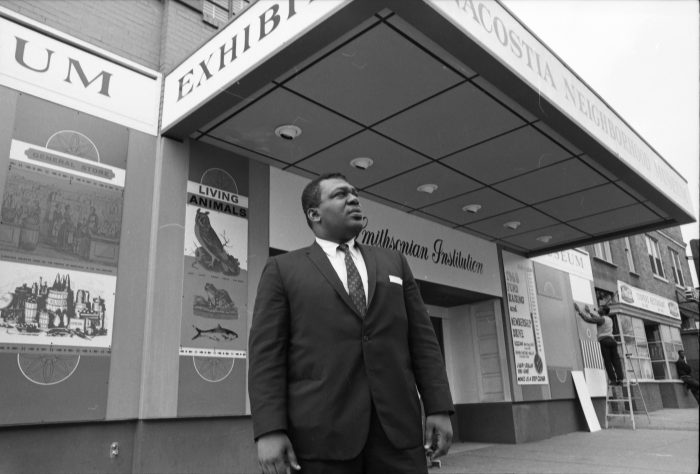

And she did. In the years that followed, Hutchinson became a community leader, a pioneer in oral history, a stalwart member of the team that shaped the Anacostia Community Museum, and, together with her colleagues John Kinard (ACM’s founding director) and Zora Martin Felton (ACM’s founding director of education), an advocate who challenged the Smithsonian to undertake a more inclusive, community-driven approach to history.

This February—my first Black History Month as Secretary of the Smithsonian—I am conscious of the many people who have guided me in my career here; those who shaped my perspective as a historian and scholar; those who helped me find a home at this Institution. And especially, I think of Louise and Zora.

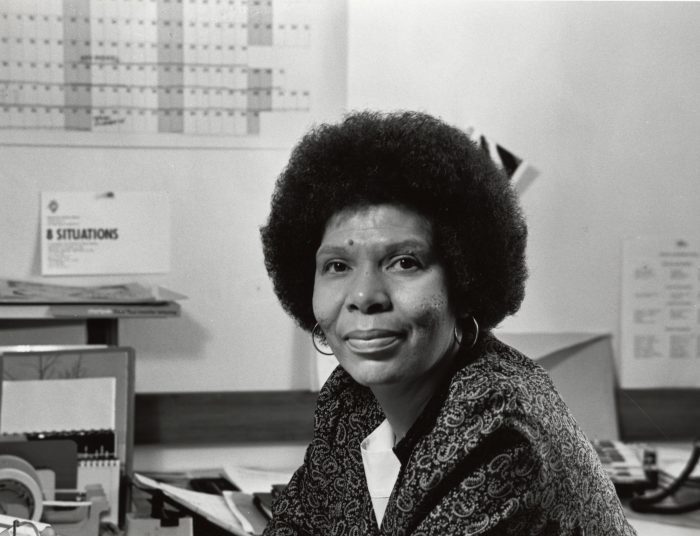

Zora Martin Felton, founding education director at the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum (now the Anacostia Community Museum) at her desk in 1983. (Photographer unknown, as featured in The Torch, November 1983)

The two became fast friends while working for the Southeast Neighborhood House, a former settlement house that provided community social services, where Hutchinson helped to run summer youth programs. When Felton learned that Kinard had been selected to direct the new Anacostia Neighborhood Museum (as it was then called), she called him up and asked for a job, becoming the museum’s first director of education. Hutchinson soon followed, joining the Smithsonian at the newly opened National Portrait Gallery before officially joining the staff of the Anacostia Museum in 1974 as historian and director of research.

Founding Director John R. Kinard in front of the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, now known as Anacostia Community Museum, May 1968. (Photographer unknown, via Smithsonian Institution Archives)

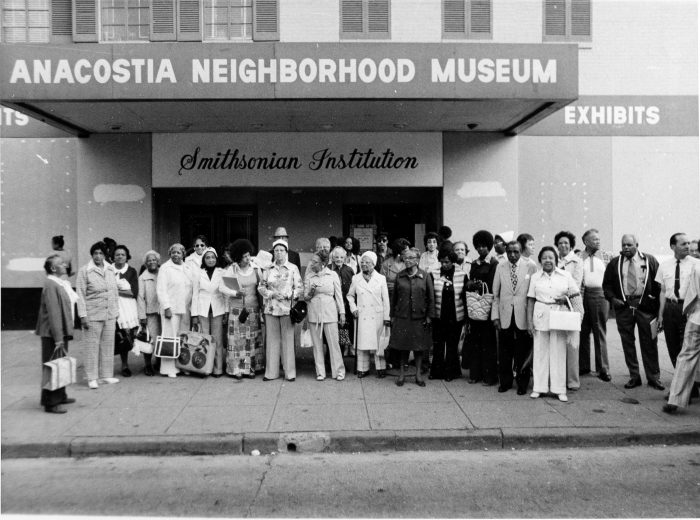

At Anacostia, Hutchinson spearheaded efforts to both preserve local stories and document African American history and culture, expanding ideas about whose culture should be preserved. She championed the museum’s oral history project, often bringing her equipment out into the neighborhood to capture the texture, tint, and tone of Anacostia life. She also helped establish the Anacostia Historical Society, a citizen-led preservation group which educated the membership and the community about Anacostia history. She and her team organized workshops to document local life, encouraging community members to bring in a range of personal objects: scrapbooks and buttons, grandma’s dishes, an aunt’s favorite gloves, and more. These, to Louise, were not casual scraps of life—they were vital pieces of history. Louise expanded the traditional canon, testing out inventive new modes of collecting, research, and storytelling. As she once told the Washington Post, “I have real concerns about the accuracy of history. I believe it must reflect the participation of all.”

The Carver Theater, before its renovation for the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, located on Martin Luther King, Jr. Ave in Anacostia. The Museum opened in September 1967 and remained at this location until April 1987, when it moved to its present location, 1901 Fort Place, S.E., Washington, D.C., and renamed Anacostia Museum. The museum is now known as the Anacostia Community Museum. (Photographer unknown, as featured in The Torch, September 1977)

Anacostia Historical Society members pose in front of the Carver Theater, which served as the first home for the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, now known as the Anacostia Community Museum. Louise Daniel Hutchinson, historian at the museum, is the seventh person from the left in the front row. (1967. Photographer unknown, via Smithsonian Institution Archives)

This work was one of the inspirations for the Save Our African American Treasures program that my colleagues and I implemented at NMAAHC. Long before we began traversing the country, collecting a Madam C.J. Walker pin or a Pullman porter’s hat, Louise had done the legwork to prove that the everyday materials of community life could tell extraordinary stories. Her work pushed the Smithsonian to expand our understanding of what can and should have a place in history.

Madam C. J. Walker (1867-1919) was an African American entrepreneur, educator and philanthropist. Her company manufactured, distributed, and sold hair care products developed for black women. She also established beauty schools across the country that trained women to work as agents, known as “hair culturists.” Walker’s beauty schools and manufacturing company offered unique opportunities for African American women when there were few job options beyond domestic service and manual labor. Pins such as this one were awarded to successful agents at annual conventions. (Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Dr. Patricia Heaston)

As director of education at Anacostia, Felton was tireless in her mission to reach and include the community more directly, to focus on issues that had real relevance and impact. “It was an exhilarating experience to be part of something we could mold and shape,” she recalled decades later in an interview with American University’s Center for Media & Social Impact. This was true, she saw, for community members as well as museum staff. “There were over a hundred people who came to our neighborhood advisory committee meetings. They just walked in the door… they were growing and developing something of their own.”

Zora’s work on the museum and the community around her was transformative. I think of the youth advisory council that she created in 1967, the Mobile Division she founded in 1969 to bring exhibitions, demonstrations, and resources into local schools, her creation of the citizen-led Friends for the Preservation of African American History and Culture, and the extensive programming she developed to celebrate local culture and history. Throughout all this work, Zora knew what was most important: ensuring that the museum was grounded in, shaped by, and dedicated to the community around her. I have always been so moved by this ethos—to always remember who we work for.

Early in my career at the Smithsonian, when the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum was still in the old Carver movie theater, I went to visit, hoping for advice and encouragement. John Kinard spoke emphatically about what a museum could and should be and the responsibilities of a curator. Many of his convictions still guide me. But that day, it was Louise and Zora whose wisdom struck me profoundly. They took me upstairs to their offices, above the rows of spectacular old theater seats, and shared with me the joy of the work they did. Louise spoke about how much better she became as a historian by doing oral histories and by getting to know the community. Listening to her discuss her work, I understood that I could learn as much from the living community as I did from the historic community.

That afternoon, Zora reminded me that the best scholar is also an educator. At that time, most of my cohort coming out of graduate school thought that the most gifted scholars didn’t need to focus on education. Zora showed me that the best scholars and best historians use their knowledge to change, to prod, to educate.

That advice and their pioneering work as black women at the Smithsonian have guided me through every position that I have held at this Institution. I hope that this month they remind all of us that the Smithsonian is at our best when we are community driven; when we strive to respond to the needs of the audiences we serve; when we value stories and contributions from every hand; when we understand, like Louise and Zora, that the time to be accountable is now.

This piece relies on research and resources from the Anacostia Community Museum and the Smithsonian Institution Archives, particularly the interviews conducted by Anna McPherson Rogers in 1987 as part of the Oral History Program.

Posted: 14 February 2020