Dr. Kay Behrensmeyer: Scaling the heights of scientific acheivement

Dr. Kay Behrensmeyer, senior research geologist and curator of invertebrate geology at the National Museum of Natural History has been selected for membership in the National Academy of Sciences in recognition of her “distinguished and continuing achievements in original research.” NAS membership, one of the most prestigious acknowledgements a scientist can receive, continues the recognition of Behrensmeyer’s impact on science and paleobiology. In 2018, she was named the recipient of two of the most prestigious honors in the field of paleontology in recognition of her monumental contributions to the field: the Simpson-Romer medal, the highest honor of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, and the Paleontological Society medal, that society’s premiere award.

In this interview for the Smithsonian.com blog, Smithsonian Voices, Maragaret Osborne catches up with Kay Behrensmeyer.

Kay Behrensmeyer pioneered the field of taphonomy, or the study of how organisms become fossils. (Smithsonian photo)

As a child, Anna “Kay” Behrensmeyer would sit down at the table with her father and listen to him talk about science. He was an architect but wanted his children to share his excitement of the wonders of the natural world. Her mother and aunts bought her science books and magazines and encouraged her to go outside and hunt for fossils.

“Looking for trilobites was the most exciting, even if we’d find just a little piece in our creek,” she recalled, referring to an extinct group of marine animals.

Years later, Dr. Behrensmeyer is now a senior research geologist and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. She’s a pioneer in the field of taphonomy, or the study of how living organisms become fossils, and was recently elected to the National Academy of Sciences — a high honor for scientists. She credits her family for setting her on the path to success.

We caught up with Behrensmeyer to talk about her more than 50-year career.

What have you been working on recently?

I study how dead remains became fossils by looking at what happens in modern environments. I take what I learn from watching carcasses decay and bones get scattered, trampled and buried to interpret the history of fossil deposits of the past. That’s kind of the nucleus of my research – understanding what happens today so I can “time travel” and reconstruct the past.

One of my major projects is in East Africa. I’m looking at what happens to modern bones in Amboseli National Park, Kenya, to find out how the dead represent the living. For example, I count what bones are preserved and what these bones tell us about the living animal populations in the Park. Are bones from large animals like elephants easier to preserve because they are big and strong, or are bones of small animals such as gazelles easier to preserve because they can be quickly buried?

Behrensmeyer records information about an elephant skeleton in Amboseli Park, Kenya. (Photo by Paul Koch)

I’ve found that the answers depend on the burial environment. This helps me interpret fossil deposits with both elephant and gazelle-sized animals, because I know that the numbers of fossils of different sized animals may not be an accurate record of their numbers when they were alive in the original ecosystem. From there, I can figure out how to correctly interpret numbers of large versus small animals preserved in fossils from the same place and time.

Has your research changed during COVID-19?

COVID has given me more sustained time to work on projects that otherwise are very fragmented by my normal museum duties. I’m writing chapters for a book about work I did in Pakistan with a big international team. Our last field season was in 2000, but we have stayed connected. The collection of vertebrate fossils is very large, and we’ve been trying to write this book about them forever. So I’m making progress on that.

What do you consider your most exciting discovery?

When I was a geology graduate student, I went on an expedition in northern Kenya. We were out looking for fossils, and I went up on this little hill that had some odd white sediment to look at the geology. Lying on top of the sediment were some sharp black rocks that looked out of place, at least to a geologist. They turned out to be stone tools that we originally thought were the oldest ones ever found.

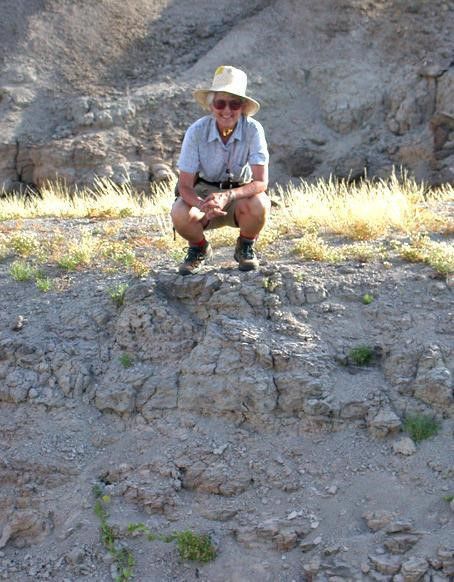

Behrensmeyer on the KBS Tuff at the KBS archaeological site, in East Turkana, northern Kenya. The site was named after her discovery of artifacts there in 1969. (Photo by David Braun)

The archaeologists came by and said, “This is an artifact site. It’s really important.” That was a pretty thrilling moment. And they named the site “KBS” after my initials (Kay Behrensmeyer Site).

That was the same year of the moon landing. So we were sitting on the shore of Lake Turkana, looking up at the moon and listening to our shortwave radio when we heard “one giant step for mankind.” We were thinking “well, here we are at both ends of human technology.” We had just learned that the tool site was 2.6 million years old. It didn’t stay that old. Further analysis changed the age to about 1.9 million years ago. But at that moment, on the lake shore in 1969, thinking across those millions of years was pretty magical.

What excites you about working at the Smithsonian?

One of the most fulfilling and exciting things about working for the Smithsonian is that we have a place where we can present our science. People by the millions can interact with it and take away important messages about how the planet works, how evolution occurs and the threats of climate change.

I can’t imagine a better place to be than at the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian. I am very lucky to have spent my career as a museum scientist.

Behrensmeyer works with Andrew Du and Amelia Villaseñor in Ileret, northern Kenya. (Photo by David Patterson)

Can you tell us more about what your recent election to the National Academy of Sciences means to you?

It’s the highest honor for a scientist in this country, and I never dreamed that I would be elected. Unbeknownst to me, my colleagues in different fields recognized what I was doing. Apparently they joined forces to support my election, and that’s how it happened.

In a way, I have to reassess my future. As a woman scientist at the National Museum of Natural History, I may be a more effective spokesperson for a lot of different causes now, including the science of paleontology and STEM education for more young women.

The Evolution of Terrestrial Ecosystems (ETE) working group at their meeting in February 2020. The ETE is a forum for early career scientists, including many women. Behrensmeyer has been co- or lead director since 1987. (Photo courtesy Kay Behrensmeyer, Smithsonian)

What is the importance of having women in STEM?

I think women, and people of all ethnic groups and diverse backgrounds bring a lot of different ways of thinking to science. And they ask different questions.

The more different kinds of people you bring together around common problems, the better off you’re going to be and the more you’re going to discover. One viewpoint just doesn’t do it. I like convergence of different ways of thinking and seeing what comes out of that.

What are you most proud of accomplishing so far in your career?

My election to the National Academy of Sciences is a huge honor, but you really can’t control whether you get recognized in that way. There are still lots of other ways to feel like you’ve accomplished something in your career. I’ve always felt my work itself was the reward, along with many wonderful colleagues who are also life-long friends.

One of the projects I’m most proud of is the “Deep Time” exhibition. It brings together a lot of things I’ve worked for my whole career. Back in the 80’s, my museum colleagues and I started the Evolution of Terrestrial Ecosystems Program to look at ecology through geological or “deep” time. This program built a foundation for us to show how earth processes and life are connected with each other, and this research contributed to the exhibit. It’s not just a dinosaur or a mammal here and an insect or plant over there. All these life forms are part of a connected system. We’re beginning to understand the connections and we made that a strong theme in the fossil hall.

Behrensmeyer in the “David H. Koch Hall of Fossils – Deep Time,” on the evening of the opening celebration in June 2019. (Photo by Bill Keyser)

The experience of bringing science to the public through a major exhibit was life changing. After seeing the new hall open and hearing so many positive responses to it, I think that’s kind of a career pinnacle for all of us who worked on it.

If you could have one mystery in your field solved, what would it be?

What would fossils look like on other planets?

I’ve just been reading about taphonomy on Mars, because scientists are thinking there might have been life there billions of years ago, and now it’s no longer there. Well, what kind of fossils might have been left? And where would we look for them? That brings us back to looking at how things fossilize. I think that’s going to be a fascinating question for the future. And eventually if we get to other planets, including moons of Jupiter that may or may not have life, how would that operate? That’s really reaching for the stars, but it’s fun to think that taphonomy can extend beyond our own planet.

Margaret Osborne is an intern in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. Her journalism has appeared in the Sag Harbor Express and aired on WSHU public radio. Margaret is an undergraduate at Stony Brook University, where she majors in journalism and German language and literature and minors in environmental studies. She’s spending her last semester in Washington, D.C. and will graduate in May.

Copyright 2020 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 3 June 2020

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature