The legacy of the last slave ship

The past is present for the descendants of the survivors of the Clotilda’s last voyage.

Congress banned the importation of new slaves into the United States in 1808, decades before the scourge of slavery itself was ended. But the mid-Atlantic slave trade was lucrative, and slavers continued their trade illegally.

The last known slave ship to transport enslaved Africans to American shores was scuttled in 1859, off the coast of Mobile, Alabama. Fearing criminal charges, the Captain William Foster of the Clotilda transferred 110 Africans by night to a waiting steamboat, before burning the Clotilda and sinking it. The fact that the Africans could not be legally enslaved because they were smuggled into the country made no difference in their status as chattel and they were distributed to the Clotilda’s financial backers and sold.

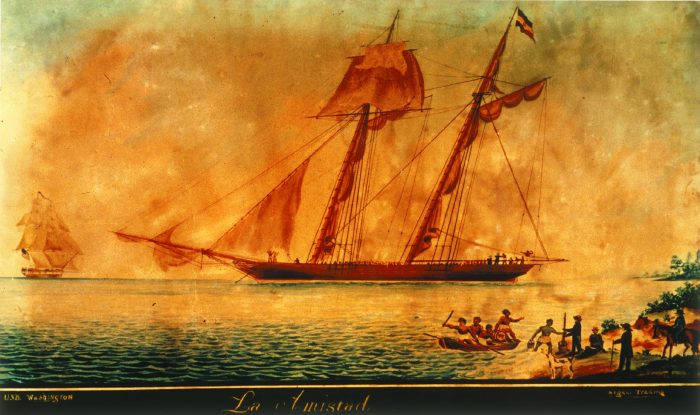

The schooner Clotilda was the last known U.S. slave ship to bring captives from Africa to the United States, arriving at Mobile Bay in autumn 1859 (some sources give the date as July 9, 1860), with 110-160 slaves. The ship was a two-masted schooner, 86 feet long with a beam of 23 feet, similar to this painting of La Amistad. Clotilda was burned and scuttled at Mobile Bay.

This is acontemporary painting of the sailing vessel La Amistad off Culloden Point, Long Island, New York, on 26 August 1839; on the left the USS Washington of the US Navy (courtesy New Haven Colony Historical Society and Adams National Historic Site)

After the Civil War, the community of Africatown was founded near Mobile by some of the Africans transported on the Clotilda. More than 100 descendants of the original founders still live in Africatown. The remains of the Clotilda were found in May 2019. How to present her history—and the lives of the enslaved persons who disembarked from her on American shores, as well as the stories of their descendants—is the subject of careful consideration.

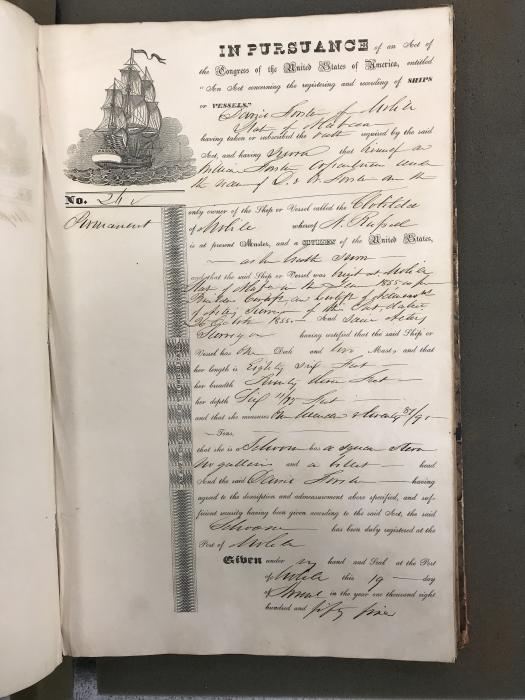

The Clotilda’s original registry.

Courtesy Alabama Historical Commission

Close consultation with those descendants will shape the narrative around treatment of the site of the wreck itself; any artifacts salvaged from her; and Africatown.

“What’s peculiar about the Clotilda is that it didn’t wreck by accident,” explains Paul Gardullo, supervisory museum curator at National Museum of African American History and Culture, as well as the director of the Center of Global Slavery there.

“It was burned on purpose,” he continues. “The people who owned the ship, who sold enslaved people stolen from their homes in Africa, burned it to cover their tracks.” (The method of the Clotilda’s destruction helps explain why it was found in a place where no other ships had wrecked, Gardullo notes.)

The Clotilda’s owners and operators—who defied the law, sailed to West Africa and forced 110 people to leave their homes and families—“lived in a country at a time where they thought they could get away with it,” Gardullo continues, referring to the story around the ship, her passengers and the attempted coverup as a “conspiracy of silence.”

There are no photographs yet of the location of the ship. Conditions where it lies in eight to ten feet of water, says SWP diver Kamau Sadiki (above) are “treacherous with visibility almost zero.” (The Slave Wrecks Project)

Along with Stephen Lubkemann, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Africana Studies and International Affairs at The George Washington University, Gardullo co-directs the Slave Wrecks Project, which has been working since 2018 on how to interpret and preserve the site and the ship’s remains. (It was that year that a journalist named Ben Raines purportedly discovered the wreck, which turned out to be a different vessel.)

The Alabama Historical Commission, in tandem with SEARCH Inc.—maritime archaeologists and divers specializing in shipwrecks—led the process of authenticating the wreck of the Clotilda. Locating her at last signals the beginning of one chapter as much as the end of another.

“This is a really important story because it opens up history in ways that people don’t normally think about,” says Gardullo. Among them: the fact that slavery continued long after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, or that slave ships continued to legally ply inland waterways in the U.S., from the Potomac to the Mississippi.

A small community just north of Mobile, Alabama, is the home of the descendants of the enslaved that arrived in the United States aboard the illegal slave ship Clotilda ( Wikimedia Commons )

Descendants of the enslaved who traveled on the ship still live in Africatown, the community north of Mobile adjacent to where the Clotilda was found. Their voices are critical as discussions about how to approach and interpret the site take place.

“One of the things that’s so powerful about this is by showing that the slave trade went later than most people think, it talks about how central slavery was to America’s economic growth and also to America’s identity,” Smithsonian Secretary and founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture Lonnie Bunch said in a 2019 interview with Smithsonian magazine. “For me, this is a positive because it puts a human face on one of the most important aspects of African American and American history. The fact that you have those descendants in that town who can tell stories and share memories—suddenly it is real.”

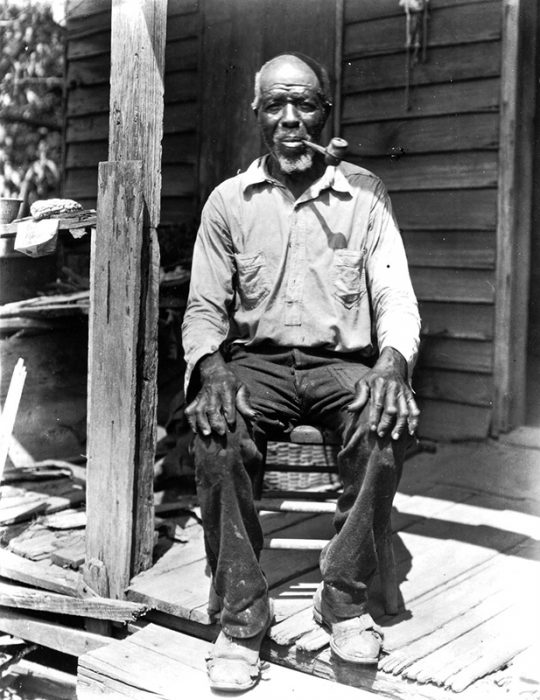

Cudjo Lewis (ca. 1841-1935) was a founder of African Town (now Africatown) in Mobile, Alabama, and was the last survivor of the Clotilda, the last ship to illegally transport captive Africans to the United States. Toward the end of his life, Lewis became famous when his story was published in a book and newspapers. (Photo courtesy Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama)

NMAHHC’s Mary Elliott, Curator of American Slavery and the lead on the Slave Wrecks Project in Africatown since 2018, is among those SI staff working closely with locals to gather their stories about ancestors who arrived on these shores on the Clotilda. The mission: to explore how the incident shaped descendants’ social, cultural and economic lives.

Elliott spent time in Africatown visiting with churches and young members of the community and says the legacy of slavery and racism has made a tangible footprint here in this place across a bridge from downtown Mobile.

“The story of Africatown is particularly special because the descendants can not only connect to individual ancestors, but through ancestral stories and archival records they are able to learn about the Middle Passage journey and their origins in West Africa,” says Elliott.

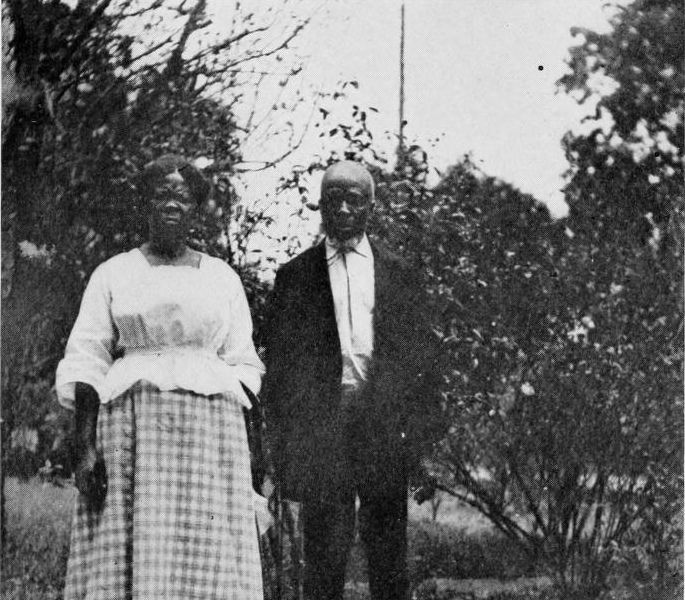

The descendants of Cudjo Lewis and Abache (above) heard stories of the ship that tore their ancestors from their homeland and now the wreck of the Clotilda has been confirmed to be found in Alabama’s Mobile River. ( Wikimedia Commons )

“Africatown, like many other historic black communities, was founded by people of African descent who survived slavery and pursued life, liberty and justice against a backdrop of racism,” she continues. “The descendants, along with other Africatown residents, continue to uphold the legacy of strength and vision while also pursuing economic, environmental, political and social justice.”

While we can find artifacts and archival records, the human connection to the history helps us engage with this American story in a compelling way. The legacies of slavery are still apparent in the community. But the spirit of resistance among the African men, women, and children who arrived on the Clotilda lives on in the descendant community in Africatown.

—Mary Elliott

The discovery of the Clotilda helps scholars better tell the story of how the slave trade shaped the world in myriad ways.

“For a long time, looking for a shipwreck [like this] was not deemed important enough, because it was not a treasure ship or a warship,” Gardullo explains. “But for us at NMAHHC, it was never a question of why these ships were important.

A wreck like this “helps us to humanize the story and bring us closer to those who were kept in the most inhumane conditions aboard these ships. The remnants of the Clotilda help us get to other questions we must ask and remind us of our collective responsibility to reckon with the past.”

Posted: 27 July 2020