#BecauseOfHerStory: Healoha Johnston

Curator Healoha Johnston Connects Asian Pacific American History to our Present

The Smithsonian’s Asian Pacific American Center (APAC) shares history, art, and culture through innovative museum experiences and digital initiatives. Sara Cohen spoke with Healoha Johnston, the Asian Pacific American women’s cultural history curator at APAC, about how she unearths stories that allow us to understand our world today.

What does your typical workday look like?

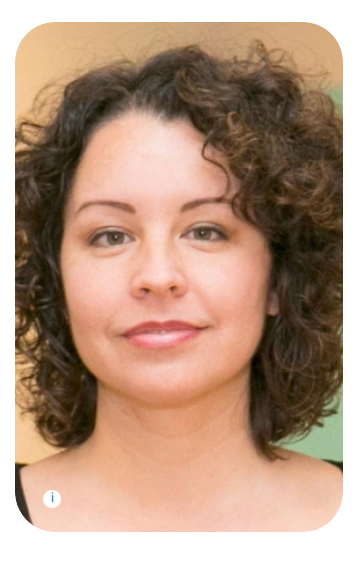

Healoha Johnston, curator of Asian Pacific American women’s cultural history at Asian Pacific American Center. Photo by Shuzo Uemoto.

My workday starts early, usually before 5 a.m. Because I am based in Hawaiʻi, I try to sync up with colleagues working in different time zones as much as possible. On an average day, I plan for future projects, research and write, and correspond with colleagues and artists.

I like finding stories in art and objects that inspire people to see things differently. I enjoy brainstorming ways to connect an object’s story to current issues. Artists make great partners in this process because they often comment on the world in ways that are creative and inspiring. Being able to research and work closely with artists motivates me to get to work before 5 a.m. every day!

Why is it vital that the Smithsonian conducts research in Hawaiʻi?

My research highlights the contributions made by women artists, intellectuals, activists, and creatives working in different fields. Many of their contributions are underrecognized, yet they offer great insights for today. Learning about these women can help us prepare to overcome unexpected challenges in the future.

As the world’s largest research and museum complex, the Smithsonian is a global institution. Our collections represent cultures and communities from around the world. Sharing resources with communities whose traditions and lifeways are connected to the collections helps make the Smithsonian relevant. Including perspectives from locations outside of D.C. helps amplify diverse voices at the Smithsonian.

What’s one women’s history story you wish more people knew?

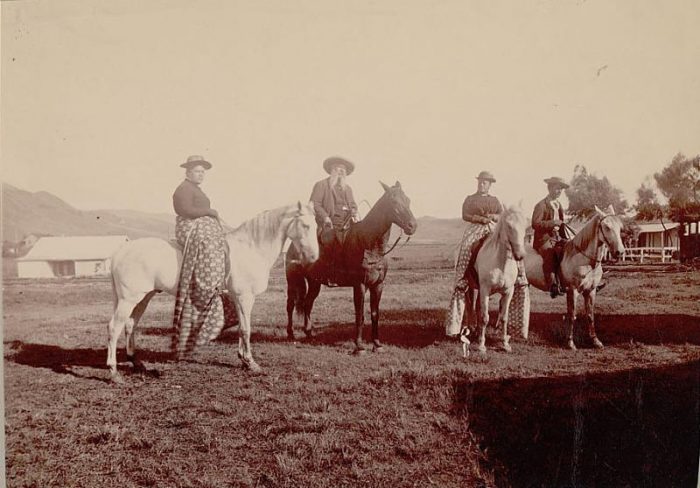

Pāʻū riders are women horse riders who wore a pant-like garment over their dresses. In the mid-19th century they adapted a customary Hawaiian garment made of kapa (barkcloth) into their new garment, made of calico or gingham. They were both fashionable and practical. Their invention enabled women to ride astride, instead of sidesaddle. These women rode faster while keeping their clothes clean and their legs covered. Photographs depict pāʻū riders standing upright, fierce, and graceful. It’s a very different depiction of women for the mid-19th century!

Two women wearing pāʻūs (riding costumes), John Cummins, and man; all on horseback; wood-frame buildings in background 1890. National Museum of Natural History, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Asian Portrait of woman wearing pāʻū (riding costume) and with headgear and riding crop. National Museum of Natural History, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

How do you remember learning women’s history growing up?

I learned women’s history from family members who told stories about Hawaiʻi’s deep cultural and political past. In Hawaiʻi, women have always held esteemed positions in society. They have been involved in government, stewarding natural resources, and passing on knowledge. Women were expected to master their given area of expertise. This history is now taught in Hawaiʻi schools so students can learn in a formal education setting what I learned from my family.

What would you say to a middle school student interested in learning more about women’s history?

Stay curious! And find a mentor. Having a mentor makes it easier to understand how to get involved in your community, and how to apply lessons form women’s history in the present day.

The Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, Because of Her Story, funds curators to research and share women’s history at museums and centers across the Smithsonian.

The Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative, Because of Her Story, funds curators to research and share women’s history at museums and centers across the Smithsonian.

Posted: 28 September 2020

- Categories: