How a little Green Book helped drive travelers to Black businesses

America’s love affair with the automobile has had its ups and downs, but piling the family into the car and heading off on a road trip is still a cherished tradition, despite the inevitable wail from the back seat, “Mom, I gotta go!”

But not long ago, the simple pleasure of a family drive was hardly carefree for Black Americans. Finding lodging, restaurants, even gas stations that would serve Black people was challenging and required careful planning.

Launching October 3 at the National Civil Rights Museum, a Smithsonian Affiliate,in Memphis, Tenn., the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Services newest exhibition—“The Negro Motorist Green Book”—examines the role of a tool that helped guide Black motorists and tourists in the first half of the 20th century.

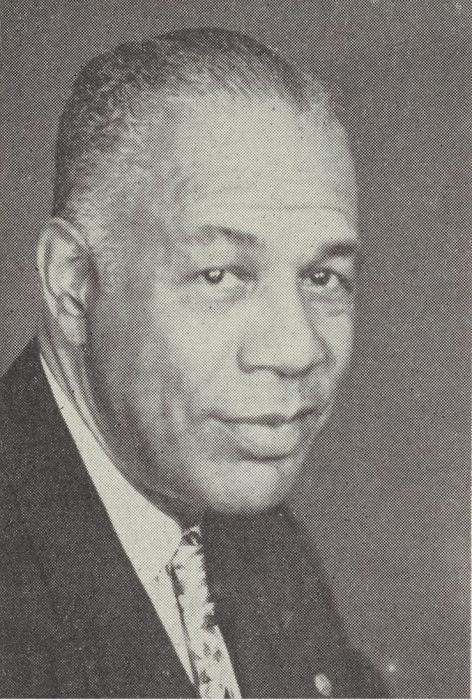

Victor Hugo Green in 1956.

Courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, New York Public Library.

Published by a postal carrier named Victor Green, the Green Book helped African Americans find places to sleep, dine, and sightsee free from racist harassment or abuse in the United States and across the world between 1936 and 1967. (The NCRM is housed at what was once the Lorraine Motel, where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968 and which was itself a Green Book site.)

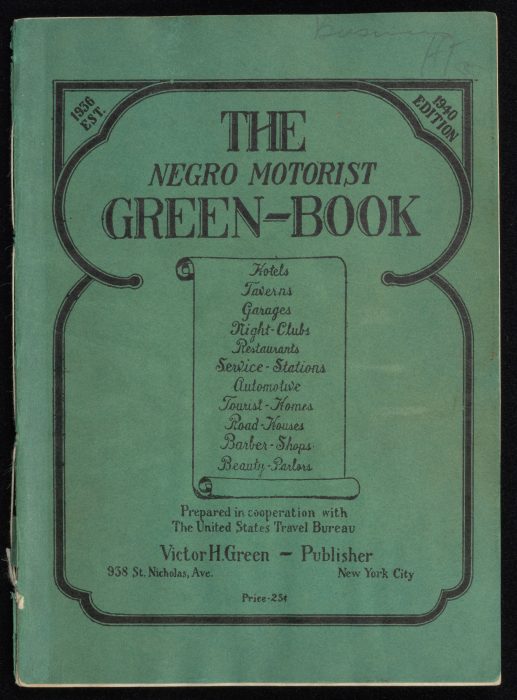

“Green Book” cover, 1940.

Courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, New York Public Library.

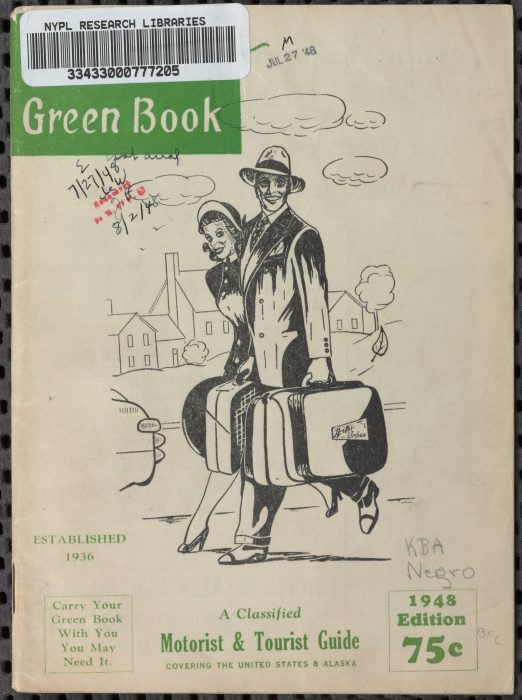

“Green Book” cover, 1948

Courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, New York Public Library.

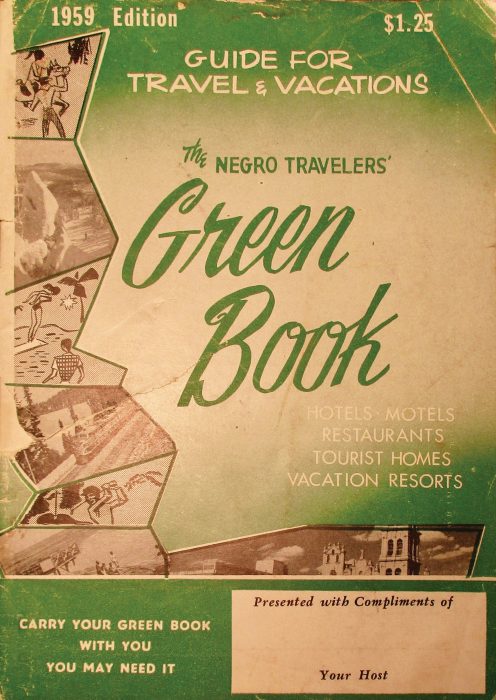

“Green Book” cover, 1959.

Courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, New York Public Library.

Organized by states, and eventually by country, Green Books were listings of restaurants, hotels, and other destinations reported by African Americans to welcome black patronage. The guides also doled out pep talks on the importance of taking time off (from the 1962 edition: “In our opinion, just as a good vacation provides respite from a tedious or demanding job, so must recreation and travel serve as a safety valve for our collective sanity”), and dispensed motor safety tips (“Slow down at intersections… you may find a stalled car there, or a pedestrian who has slipped and fallen… almost anything can happen”).

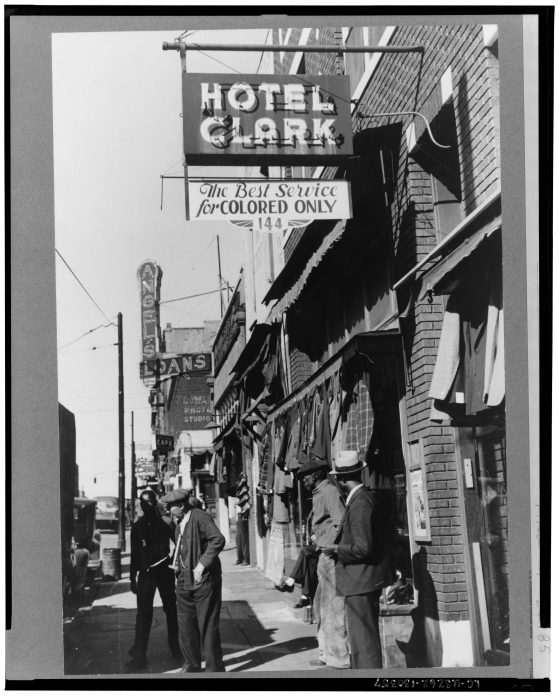

Hotel Clark on Beale, Street, Memphis, Tennessee, 1939.

Marion Post Walcott, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection – LC-DIG-ppmsc-00197.

All-Negro Staff in Newark, New Jersey., station: Dudley Johnson, manager, Marion T. White, Arthur Smith, and Leonard S. Coleman.

Courtesy of Anthony M. Smith, Sr.

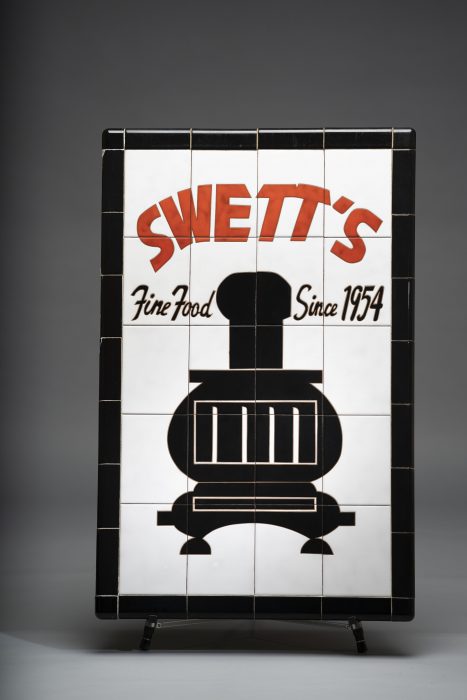

Swett’s Restaurant sign, Nashville, Tennessee.

Courtesy of Swett’s Restaurant, Nashville, TN

Photo by James Kegley.

While others published similar guides, “the Green Book had the longest tenure and reached the most people,” says the exhibition’s curator Candacy Taylor, author of Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America (Harry N. Abrams, January 2020).

Taylor is an independent scholar and Green Book authority who has catalogued more than 10,000 Green Book sites and visited more than 4,000, including a long-gone Black-owned dude ranch in Victorville, Ca. that catered to celebrities such as boxer Joe Louis, and the R & R Liquor Store in Nashville that is still in operation.

Taylor says that the first edition of the Green Book, published in 1936, was mostly a listing of what we would think of as gas stations—automobile garages and mechanics in and around New York’s Harlem neighborhood, with a few motels thrown in. As Green gathered more leads and tips about places to go and to avoid from his fellow mail carriers, and then from the general public, subsequent editions of the Green Books grew rapidly. Green also shrewdly asked his postal carrier colleagues to pitch the Green Book to businesses on their route as a place to advertise. “Companies didn’t have to pay to be listed,” Taylor explains, “but the larger ads cost money.”

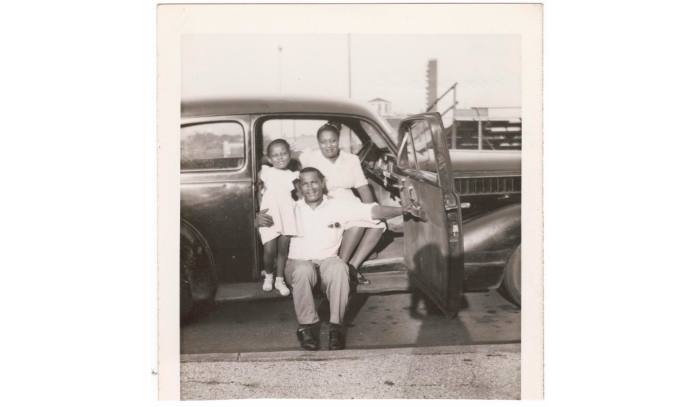

Unidentified family posed inside a car, ca. 1950.

Gift of Princetta R. Newman, National Museum of African American History and Culture. © NMAAHC

Outdoor Photo of a mother, father, and child Standing by a Car, 1940.

Photo: Rev. Henry Clay Anderson. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. © NMAAHC

Four young African American women standing beside a convertible automobile, ca. 1958.

Courtesy WANN Radio Station Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

NMAH Archives Center

Negro boys on Easter morning. Southside, Chicago, Illinois, 1941.

Russell Lee. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Photograph Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-00256.

Boys Leave for Orthopedic Camp, July 3, 1958.

Photo: Ross Pearsons. from The State Newspaper Photograph Archive [state_015_0061]. Courtesy of Richland Library, Columbia, S.C.

Within a couple of years, Green had launched his own publishing company to focus on the Green Book. Ad sales underwrote its publication, and he hired his wife and a few others help run Victor H. Green & Company out of a Harlem office building (the site today of an IHOP restaurant.) Profits were slim (it is unlikely that Mrs. Green drew a salary), so Green continued delivering the mail well unto the 1950s.

A turning point for the Green Book’s reach came when Victor Green approached ESSO (now part of the Exxon Mobil Corporation, the exhibition’s sponsor) about carrying the guide at their gas stations. “ESSO really stood out as a company that supported Black entrepreneurship, that hired Black chemists and marketing executives,” Taylor notes. ESSO said yes to Green’s overture, and soon the Green Book was distributed across the nation.

“The Green Book story is very appealing to our colleagues around the nation, so “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” will tour ten cities around the United Sates through 2024, says Marquette Folley, project manager and content director at SITES.

“I am moved by the stories of these [Green Book-listed] businesses, these funeral homes and beauty parlors and banks,” Folley adds. “These are stories we benefit from hearing. Even in the light of [racist] inequities, there is the reality of all these strong Black-owned businesses, run by people with intelligence and elegance and creativity, people descended from enslaved persons. Enslavement is one part of the story, but not the only part.”

Victor Green died in 1960, and his wife Alma took over as editor. The final editions of the Green Book spanned multiple countries in Africa and Europe, as well as Canada and Mexico, with the last edition published in 1967.

Cash Register, Threatt Filling Station, Luther, Oklahoma, (c.1950s) Oklahoma, (c.1950s)

Courtesy of the Threatt Family of Oklahoma

Photo by James Kegley

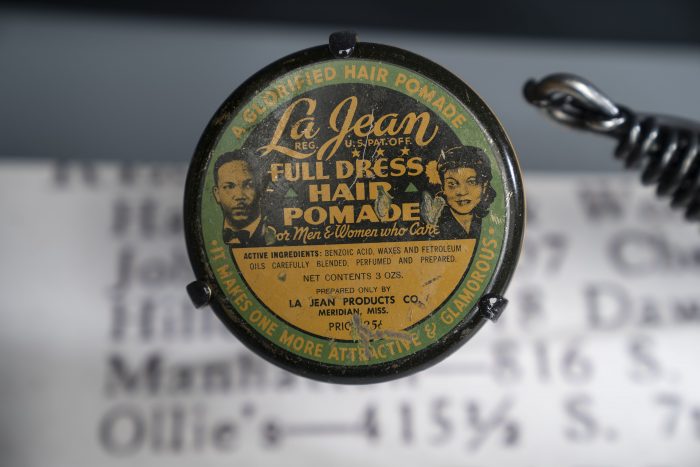

La Jean full dress hair pomade (c.1940s).

From the Velvatex College of Beauty Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Courtesy of the Mosaiac Templars Cultural Center, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Photo by James Kegley.

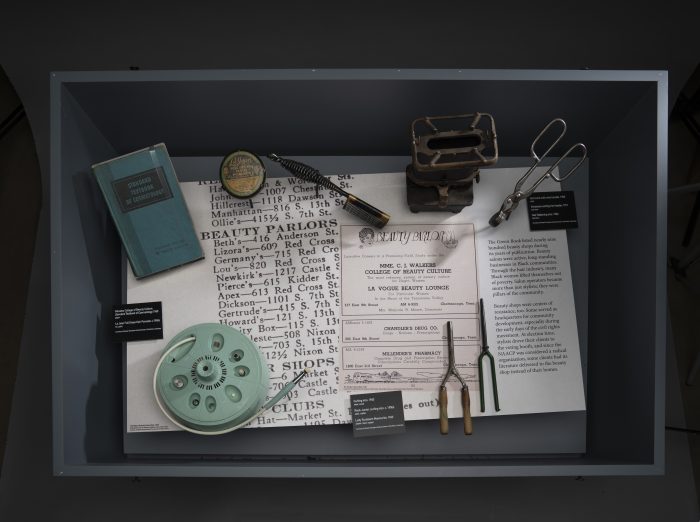

Beauty salon objects from the Velvatex College of Beauty Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Clockwise from bottom left:

Lady Sunbeam manicurist (1960); Standard Textbook of Cosmetology (1960); La Jean full dress hair pomade (c.1940s); hot comb (1900); kerosene curling iron heater (1911); hair flattening iron (1906), curling iron (c.1950s); curling iron (1940)

Courtesy of the Mosaiac Templars Cultural Center, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Photo by James Kegley

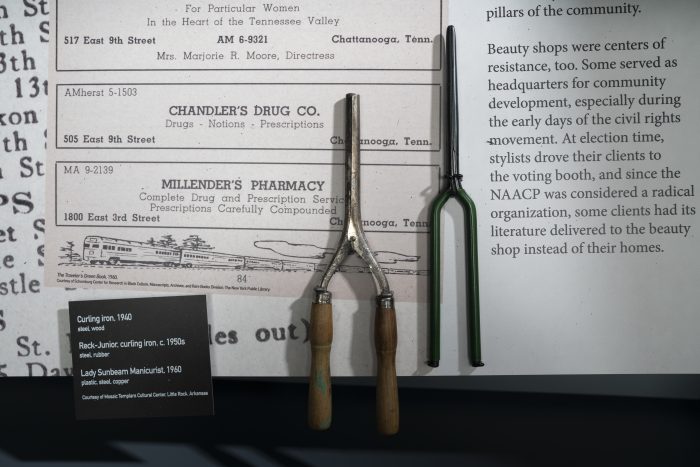

Left: Curling iron with wooden handles (c.1950s)

Right: Curling iron with green rubber handles (1940)

From Velvatex College of Beauty Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Courtesy of the Mosaiac Templars Cultural Center, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Photo by James Kegley

What would Taylor have visitors to the exhibition take from it?

“Despite all of the hurdles and the horrific realities that Black folks faced, whether from lynching to harassment to sundown towns, that we did not just persevere—we triumphed in ways that most people don’t know. There is a strength and resolve in what’s possible for us, and we have this history to celebrate, but also to preserve and protect.

“I hope that people [visiting the exhibition] feel empowered and invigorated by this rich history,” she adds.

“The Negro Motorist Green Book” will be on display from Oct. 3 through Jan. 3, 2021 at the National Civil Rights Museum, a Smithsonian Affiliate. The exhibition was created by the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service in collaboration with Candacy Taylor and made possible through the generous support of Exxon Mobil Corporation.

Many of the images from the exhibition shown in this article are on loan from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a research division of the New York Public Library, whose director, Kevin Young, will assume the directorship of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Posted: 5 October 2020