Get to Know the Scientists Discovering Deep-Sea Squids

What more appropriate way to celebrate World Ocean Day?

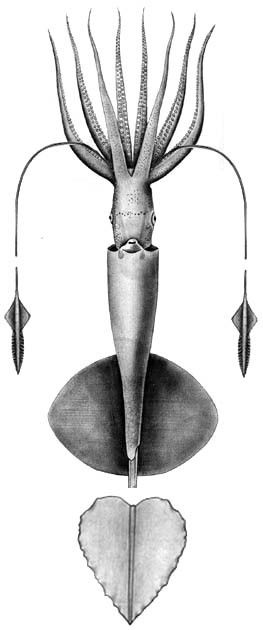

The Pacific bigfin squid (Magnapinna pacifica) in the Smithsonian collections that Mike Vecchione and Richard E. Young used to describe the deepest-known species of squid. (Richard E. Young)

When a Virginia Institute of Marine Science professor interviewed Mike Vecchione for graduate school admissions and asked him what he wanted to do, he replied that the only thing he knew for sure was that he didn’t want to use a microscope.

“It turned out he was in charge of the plankton department,” Vecchione laughed. “So his revenge was to accept me as a student and give me an assistantship sorting plankton under a microscope.” But when Vecchione poured his first jar to sort, out plopped a squid that had gotten caught in the sample of small animals. “I looked at it and said, ‘That’s what I want to work on right there.’”

Four decades later, he studies squids and octopuses as a curator of cephalopods — the class of marine invertebrates that includes squids, octopods, cuttlefishes and nautiluses — and pteropods — free-swimming sea snails — as a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration scientist stationed at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Erin Malsbury chatted with Vecchione to learn more about the wonderfully weird world of cephalopods on World Octopus Day for the Smithsonian magazine blog, Smithsonian Voices.

Why do you study the deep-sea?

Depending on how you do the calculations, somewhere between 95 and 99% of the living space on the planet is in the deep sea. People walking around on land is a very small part of it, in spite of our large impact. So studying deep marine organisms is really important for understanding life on our planet. I study the ocean because it’s so poorly known. Almost every time we look, we find something new.

Mike Vecchione pulling in a net on a research vessel. (Photo courtesy Mike Vecchione)

You focus on cephalopods for your research. What do you find most interesting or important about these animals?

One reason they’re so interesting is they are intelligent invertebrates. Almost everything that we think of as being intelligent — parrots, dolphins, etc. — are vertebrates, so their brains are built on the same basic structure. Whereas cephalopod brains have evolved from a ring of nerves around the esophagus. It’s a form of intelligence that’s completely independent from ours.

Alongside this peculiarly evolved intelligence, it turns out that squids have what are called giant axons — really large nerves. And because they’re giant, that makes them easy to do experimental manipulations with. A lot of what we know about how nerves function comes from working with squids.

A National Institutes of Health researcher in Woods Hole, Massachusetts examines the giant axon of a squid. (Photo courtesy NIH History Office)

They’ve also become important models for other types of research, like camouflage because they can change their appearance — colors, textures and all that — in the blink of an eye.

Within marine ecosystems, they’re an important link in the food web because they’re really voracious predators — they eat a lot of stuff — and they’re food for other organisms. Lots of fishes, whales, birds and other animals eat cephalopods. People eat them too, so they’re important for fisheries.

You’ve been going out to sea and working with these animals for over 50 years. What’s surprised you the most?

Probably the biggest surprise I had was discovering the deepest kind of squid, the Pacific bigfin squid (Magnapinna pacifica). The first time I got a video of one, I was so excited I jumped out of my chair. It was sent in by a woman whose boyfriend worked on an oil exploration vessel in the Gulf of Mexico. The team on the vessel was doing remotely operated vehicle (ROV) — robot submarine — dives, and the woman’s boyfriend just happened to stick his head into the ROV operations shack when the team saw this squid. The boyfriend said, “My girlfriend’s really interested in marine biology. Can I get a copy of that video for her?” So she got it and tried to figure out what it was unsuccessfully.

When people can’t figure out what something is, a lot of times they find their way to the Smithsonian. So this woman eventually contacted me and said, ‘I’ve got this video of a 21-foot-long squid. Do you want to see it?’ Of course I said yes.

At the time, we didn’t know about this kind of squid, and I was thinking, “Well, if it’s 21 feet long and in the deep sea, it’s gotta be a giant squid.” But when I saw that video, I immediately realized that it was unlike any known cephalopod.

We also recently published a paper on the deepest record of a cephalopod — the first octopus or squid seen in a deep sea trench. It was one of the Dumbo octopods (Grimpoteuthis) that has fins that look like Dumbo ears. We found it about 4.3 miles deep in the Indian Ocean which is more than a mile deeper than the previous depth record for a cephalopod.

A dumbo octopus drifts through the cold, pitch-black, high-pressure water of the deep sea. (photo courtesy NOAA Okeanos Explorer)

The Smithsonian houses thousands of cephalopods in its collection. What makes the museum’s collection unique? And how do you use the specimens for research?

We’ve got probably the most diverse collection of cephalopods anywhere. My favorite stuff in the collection are the type-specimens for some of the weird deep-sea species. Not just a single one, but the category of deep-sea type-specimens. They’re the most important part of the collection, because those are the specimens that are used when a new species or higher-level taxon is described. The Smithsonian has over 200 cephalopod type-specimens.

Work with the collection might involve pulling specimens to look at physical characteristics. For instance, I recently published a paper with colleagues in Ireland. They were doing DNA identifications, and they wanted me to do the morphological — physical trait-based — identifications and see how they matched up. They sent me the cephalopods they had collected, and I went through jar after jar comparing them for identification.

Grimalditeuthis bonplandi, a squid found in the deep sea near Southern California, uses its long tentacles like fishing lures to attract prey. The Smithsonian has 20 specimens of this squid as well as three genetic samples. (Richard E. Young)

And the most important question: what’s the plural of “octopus?”

That’s a question I hate. People get so wrapped up in it. They’ll argue about whether it’s “octopuses” or “octopi” or “octopodes.” I will call something “octopuses” if you’re talking about something that’s in the genus Octopus. Other than that, I refer to them as “octopods,” because they’re within the order Octopoda. But it really doesn’t matter as far as the animals are concerned.

Erin Malsbury is an intern in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. Her writing has appeared in Science, Eos, Mongabay and the Mercury News, among others. Erin recently graduated from the University of California, Santa Cruz with an MS in science communication. She also holds a BS in ecology and a BA in anthropology from the University of Georgia.

Copyright 2020 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 8 October 2020

-

Categories:

Feature Stories , Natural History Museum , Science and Nature