Black Family History

I know the challenges African Americans face in researching family history. I also know how it feels to find family members despite these obstacles—the flood of emotion, the power of connecting with your roots.

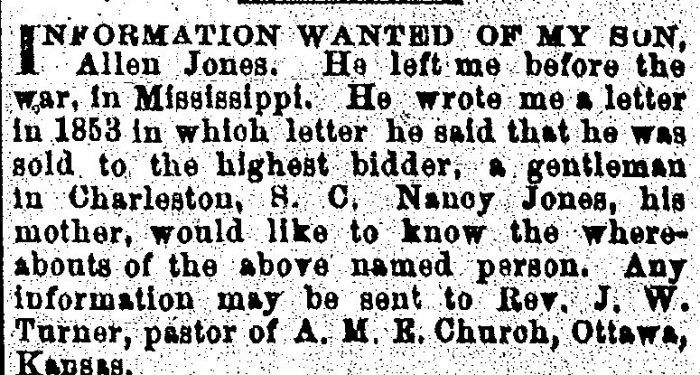

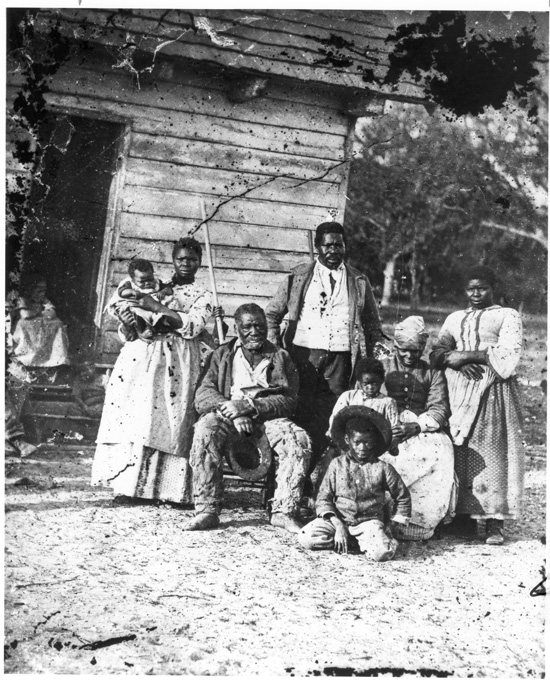

During Reconstruction, former slaves placed advertisements and letters in newspapers around the country, trying to find family members that they’d been separated from, in some cases decades prior. Reading through these records in collections of the Freedman’s Bureau never fails to move me – the tragedy of those losses, the indefatigable hope that reunion might still be possible.

These letters speak poignantly across the years; they remind us of the horror and cruelty of an institution that tore loved ones apart; they remind us of the will and resilience of those who endured; they remind us of the sacred power and strength that joins family together across miles and generations.

This Black History Month, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History chose the Black Family as their area of focus. As I reflect this February, it’s the fragments from my own family history, the partial sketches of ancestors passed down through colorful oral histories and shared memories, that remind me of the importance of family stories in strengthening our ties to previous generations.

Several years ago, I headed across the National Mall to the National Archives. I was taking a pause from exhibitions research in favor of some personal research: I wanted to see if I could learn more about the earliest of my Bunch ancestors whose name I know: Candis Bunch. Candis was an enslaved woman whose name I’d previously discovered attached to the marriage license for her son, my great grandfather Oscar Bunch. That day at the Archives, I found mention of her death in 1870 as a 40-year-old freed woman in Wake County, North Carolina.

Piecing together those remnants of Candis’s life turned out to be a daunting project. It would be years later, hunting through the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, that I unearthed a labor contract between her and a landowner. She’d received $11 for 44 days of farm work in 1867 and purchased items such as starch and seed cotton from the landowner.

Reading that list of items rocked me. Because there, in front of me, was the link between Candis’s life and my own. For 60 cents, she had bought two baking tins in the shape of hearts and crescents. And I remember my own grandmother, Leanna, baking cookies in the shapes of hearts and crescents for me as a child.

I am inspired by women like Candis, who, despite all they experienced, preserved their humanity and protected their families as best they could. By men like my grandfather, a sharecropper, who took 10 years to get through college. For a decade, he picked cotton every day and studied books all night because he believed he could become something more. These stories have always inspired me to challenge myself and to persevere. My family history not only helped put my own life into context; it inspired me to take the path that led me to where I am today.

I know the challenges African Americans face in researching family history. I also know how it feels to find family members despite these obstacles—the flood of emotion, the power of connecting with your roots. That’s why I am so proud of the work of NMAAHC’s Robert Frederick Smith Explore Your Family History Center. The center helps visitors begin learning their family history and researching African American genealogy, offering the practical advice and resources I wish I’d had when I started my journey. Located directly above our history galleries of the museum, the Family History Center connects those deeply personal stories to the larger arc of our nation. It reminds visitors that their family history is part of American history, that the stories they learn about in a museum belong to them, their families, and their communities.

Now that I am a grandfather myself, I reflect on how I want to pass those Bunch stories down to my grandchildren: sharing the family lore, baking heart-shaped cookies, teaching them that they too are a part of this history. Teaching them that the story of America is intensely personal, that it was shaped by their ancestors, and that it will be the inheritance they pass on to their grandchildren.

Posted: 23 February 2021

- Categories: