The Power of Olympians

As I watch this year’s Olympics in Tokyo, I am again reminded of the transcendent power of sport to inspire us to set our sights higher, to prove that what seems impossible can be accomplished. And most importantly, to live up to the values we have long aspired to as a nation by working to level the playing field.

Watching Simone Biles somersault through the air, Katie Ledecky rocket through the water, or Noah Lyles explode off the block brings back memories. Since I was a kid, I have been in awe of Olympians like these and their breathtaking displays of sheer athleticism. I continue to marvel at the strength, the skill, the grit, and the grace. But it was not until 1984, when I curated “The Black Olympians” exhibition at the California African American Museum, that I began to connect with the athletes and their stories on a deeper level. Opening just in time for the Los Angeles games, that exhibition helped me appreciate the cultural power of Olympic athletes and their ability to shape national discourse and understanding.

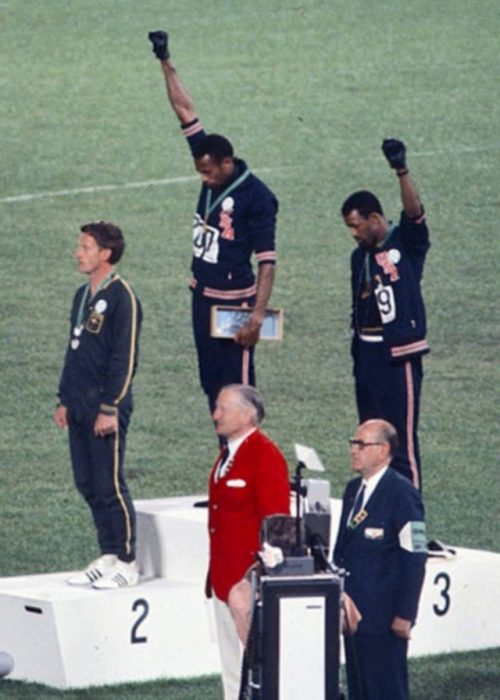

When the national anthem began to play at the medal ceremony of the 1968 Olympic Games, U.S. Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos bowed their heads and raised their fists. Having won gold and bronze respectively in the 200-meter sprint in Mexico City, Smith and Carlos had a literal platform, a podium from which they could make a symbolic statement that still resonates today.

The black gloves they wore signified unity and strength; their black socks without shoes represented the widespread poverty of African Americans back home. Carlos’ unzipped tracksuit jacket expressed solidarity with U.S. blue-collar workers, and both wore beads in honor of lynching victims. As is often the case in hindsight, Smith and Carlos have been lauded as heroes for their courageous display. At the time though, they were booed, told to leave the stadium, and the U.S. Olympic Committee suspended the two athletes.

While putting together “The Black Olympians” show in California, I had the chance to meet John Carlos and Tommie Smith in person. I had called a meeting of several Olympic athletes from the ’60s through the ’80s. As a young curator, I was making a lot of it up as I went along, desperate to convince these iconic athletes to participate. They were wary, likely having heard many spiels like mine before, so I was getting flustered and frustrated. As I did, my New Jersey accent started coming out. John Carlos said to me, “Wait a minute. You sound like you’re from Jersey. Are you from Jersey?” Carlos was from Harlem, so he knew what he was hearing. He stood up, and he said, “This guy is from Jersey. You can trust him.”

In trusting me with their stories, Smith and Carlos opened my eyes to the responsibility they shared as Olympic athletes and continued to feel all those years later. They explained why they felt compelled to act, describing how they found the courage and strength in that once-in-a-lifetime moment on the podium. And they challenged me to rethink the way I understood the role of sports in our democracy, changing me as a curator and as a citizen.

As I watch this year’s Olympics in Tokyo, I am again reminded of the transcendent power of sport. Though most of us will never compete in front of millions or receive an Olympic medal, we can all learn from the lessons athletes like Smith and Carlos offer. They inspire us to set our sights higher. They prove that what seems impossible can be accomplished. And most importantly, they challenge us to live up to the values we have long aspired to as a nation by working to level the playing field.

Posted: 27 July 2021

- Categories: