Curator Angela Tate Spotlights the Contributions of African American Women

Angela Tate works as curator of women’s history at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. She acquires works for the museums’ collections and writes scholarly articles. She also advises leadership on topics that center African American women and gender. Sara Cohen of the American Women’s History Initiative, spoke with Tate about the role of African American women in shaping American history.

Can you describe your role at the National Museum of African American History and Culture?

My role is to look at U.S. history through the lens of African American women. One example of this work is writing I did around Juneteenth. Juneteenth remembers June 19, 1865, when Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas. He informed the enslaved African Americans of their freedom and that the Civil War had ended. I looked at the role of Black women’s organizations in Juneteenth celebrations. Women have been the keepers of the flame of history. They have passed down rituals and celebrations. They’re in the kitchen cooking for these gatherings.

In the article where I discussed Black women’s work to mark Juneteenth, I also mentioned Anette Gordon-Reed’s recently published book, On Juneteenth. In interviews for the book Gordon-Reed said that she didn’t know Juneteenth was vital. She spoke to her great-grandmother and grandmother, who impressed upon her the importance of the holiday. Women have passed down not just Juneteenth but Black history in general.

I also wrote about why Juneteenth is important in the United States and across the world. The holiday is related to emancipation celebrations across the African diaspora. The story of African Americans begins with the Transatlantic slave trade, which connected most of Africa to all parts of the world. Today, Juneteenth is relevant to Africa and the Caribbean. It’s relevant any place where there’s an African diasporic community.

What’s one women’s history story that you wish more people knew?

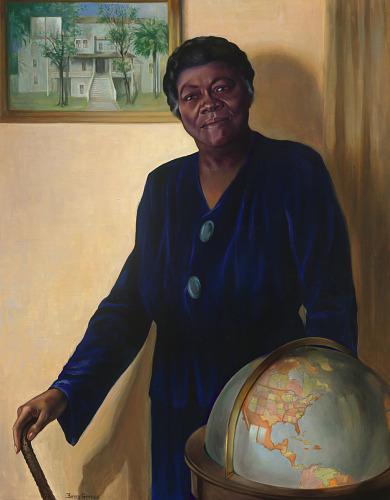

Educator and activist Mary McLeod Bethune should be more well known. When I recently took visitors through NMAAHC, they asked who she was. Bethune founded the National Council of Negro Women in 1935 and acted as their first president. She is the reason why Black women were allowed to enlist in the military in World War II. She was also close friends with Eleanor Roosevelt.

The council influenced civil rights, education, U.S. relations with Africa, and other 20th-century movements. Mary McLeod Bethune, the council, and council presidents who came after her should be highlighted even more. NMAAHC highlights her and the National Council of Negro Women in the Making a Way Out of No Way exhibition.

Was there a moment that changed how you think of women’s history?

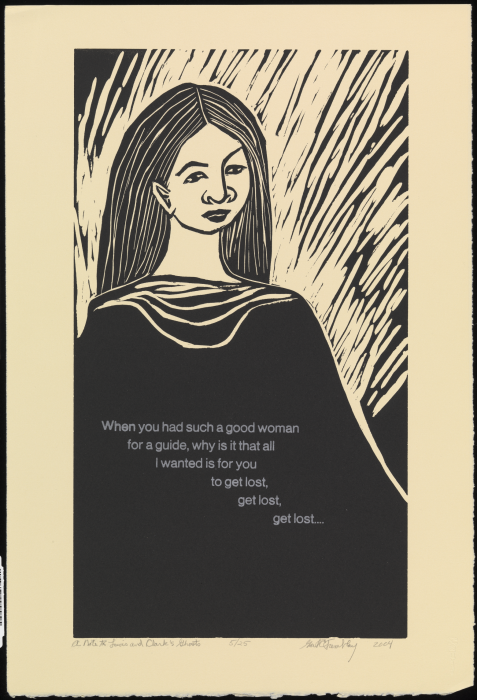

Two key moments come to mind. When I was a child, I read a book about Sacagawea’s role in the Lewis and Clark expedition. I was drawn into her world as she led them across the frontier. That was the first time I thought, “Oh, a woman was here in this crucial moment in a leadership role.” Centering her experience shares a very different perspective than that of the white men that she led. Of course, westward expansion is more complicated than what I understood as a child.

In college, I took a class on women’s history to a fulfill a graduation requirement. The professor changed my entire perspective on history. One unit looked at the 1920s after the passage of the 19th Amendment. I assumed that the 1920s were all about flappers, prohibition, and drinking. When pop culture depicts 1920s as frivolous, that hides the historical currents. The professor made me think about the 20s as a period of resistance. It was a time of continued struggle against sexism and misogyny. It also made me think about how fashion, makeup, and cosmetics are political. That professor taught me that so many of the choices women have made reflect their awareness of how they impact society, politics, and culture.

What would you say to a student interested in learning more about women’s history?

Interview your relatives about their experiences. Oral history is an unsung source to preserve history and culture. Understanding “wow, my mom (or my grandmom, aunt, or older sister) experienced things that I experienced” builds a narrative. Oral histories allow you to see that women’s stories are just as important as men’s stories.

Also, always be curious about everyone. That has served me well. Curiosity inspires me to strike up conversations with people. They illuminate experiences that I never would have thought about.

This post by Sara Cohen was originally published by the Smithsonian American Women’s History Initiative on the blog, Because of Her Story.

Posted: 27 October 2021