A Walk to Remember: Indiana’s Place as the Crucible of American Music

With its plentiful natural resources and proximity to shipping routes, the small town of Richmond, Indiana, made perfect sense as the chosen location for a late-19th-century piano company. As the crucible of early American jazz, blues and country recordings, though, it’s far more improbable.

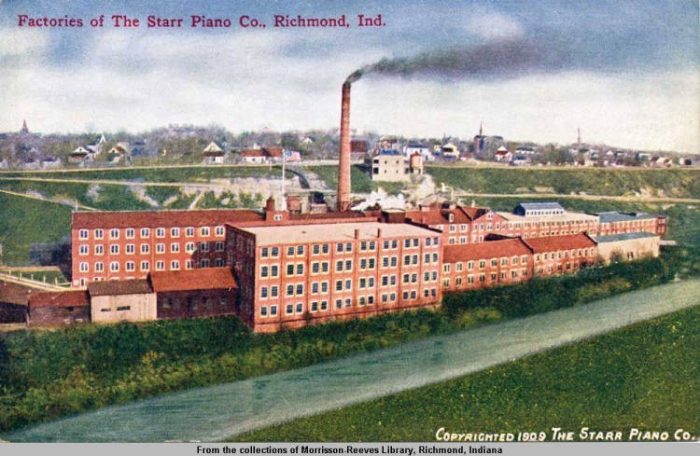

Located 65 miles east of Indianapolis near the Ohio border, Richmond offered an industrialist’s dream: a veritable army of craftsmen—many of them recent European immigrants—to provide the skilled labor a quality piano needed, plentiful forests to provide the timber, and easy access to the mainline C&O Railroad to receive supplies and ship out finished goods. It was there, in 1878, that a fledgling piano company set up shop a mile from the city center in a secluded glacial valley with the swift-running Whitewater River providing power to the new factory.

As explained by Rick Kennedy, a longtime music writer and book author, the business had changed hands and names by 1893 when it took on the moniker it would keep for the next six decades: the Starr Piano Company. In an era when every respectable household needed a piano, Starr was quickly becoming one of the finest brands around, keeping elite company with such storied names as Baldwin and Steinway. Starr pianos were exhibited at World’s Fairs and exhibitions, winning several industry awards along the way.

The company thrived, and its industrial complex soon sprawled across 35 acres in what was referred to locally as Starr Valley. By 1915, the company had sold more than 100,000 pianos and was producing another 15,000 a year.

The Times, They Were a-Changin’

Despite their plentiful successes and accolades, Starr pianos were becoming ever more threatened by the must-have gadget of the times, an invention that offered an entirely new way to experience music at home—no musical aptitude required. The phonograph, older by some 15 years than the Starr Piano Company, had outgrown its awkward and protracted adolescence and was no longer a faddish novelty. Starr, now owned by the Gennett family, fully recognized the threat the phonograph presented to its decades-old business model, and with exclusive patents that had protected phonograph technologies now expiring, the Gennetts decided it was time to diversify.

“They had the woodworkers, they had the [woodworking] machines, and they had the know-how, so it was a natural progression from an industrial standpoint to go from one form of home entertainment to another; it was a logical transition into a new form of music,” explained Charlie Dahan, a professor in the Department of Recording Industry at Middle Tennessee State University. “A good company sees those changes and adapts with them.”

The Gennetts were nothing if not adaptable, agreed Linda Gennett Irmscher. Along with Dahan, she’s the author of “Gennett Records and Starr Piano” as well as the great-granddaughter of Henry Gennett, one of the original founders of the company. “They’d always been ahead of their time and able to plan ahead,” she said. “I just think that our family was good at seeing what was coming.”

Despite complex legal wranglings over patent disputes, it wasn’t long before Starr-branded phonographs appeared alongside Starr pianos in the company’s network of stores. And the next logical step? “Listen,” said Irmscher. “If you’d bought a phonograph, you needed records—so why not make those, too? They had a network of stores across the United States, so it was a natural outlet for the records.”

Musical Stardust

After a brief stint under the Starr name, the family founded a new label, Gennett Records, in 1917 and opened a recording studio in Manhattan. While that initial location is all but forgotten today, the Gennetts’ second recording studio, built four years later on the grounds of their combined piano and phonograph factory, changed the face of music forever.

As chronicled in Kennedy’s book, “Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy,” the Richmond recording studio was situated alongside a row of warehouse buildings on a concrete floodwall against the Whitewater River. Previously a kiln for drying lumber, the studio was a scrappy affair. It was kept uncomfortably warm even in winter, as the wax masters upon which the recordings were made needed to be soft and pliable; summertime in the humid valley rendered the studio nearly unbearable. Photographs of recording sessions showed sweat-drenched musicians looking like they’d performed in the rain.

If the recording conditions were bad, the acoustics were perhaps even worse. A railroad spur that serviced the still-active industrial complex ran just feet from the rudimentary studio’s front door, and while sawdust was packed between the interior and exterior walls in an ineffective attempt at soundproofing, nothing could stop “the sound of the C&O trains roaring down the top of the ridge, thundering into downtown. They shook the whole valley,” said Kennedy. Every take of every song was timed around the movements of the trains.

Although Gennett Records would soon embrace newfangled electric technology, recordings in the early years were done acoustically: Musicians would gather into the hot, cramped space and play into megaphone-like horns that transferred their sounds via a diaphragm to a recording stylus in an adjoining room that traced the vibrations onto a wax master disc. Primitive sound mixing was achieved by locating the loudest instruments farthest away from the horn, an arrangement that necessitated multiple takes to find the right balance. A young Louis Armstrong—playing second cornet in King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band—famously had to be placed some 15 feet back from his bandmates lest his powerful playing overwhelm the mix. Without overdubs, multitracking or any other modern tricks of the trade, Gennett musicians played till they got it right.

For all its shortcomings, the sounds that came out of the Gennett studio still echo today. “America’s greatest contribution to cultural history is its music,” averred Dahan, “and no matter what kind of music you listen to, it’s been influenced directly by the records made by those artists of Gennett records.”

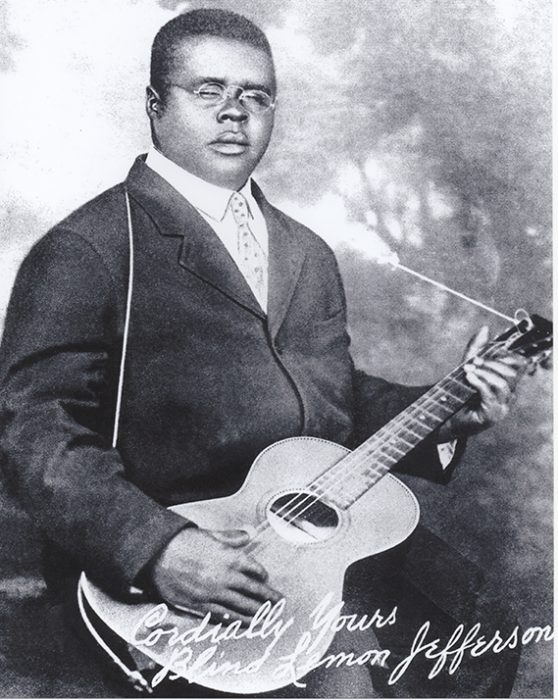

Those artists include a veritable who’s who of the early 1900s music scene, many of whom are household names today. In addition to Louis Armstrong and his mentor King Oliver, Gennett Records hosted Duke Ellington, Bix Beiderbecke, Blind Lemon Jefferson and Charley Patton. It was here in 1927 that Hoagy Carmichael recorded “Stardust,” an American classic that is estimated to have been covered some 1,500 times since. Even Gene Autry, the Singing Cowboy of film and television, laid down tracks in the Indiana studio.

All That Jazz

Gennett Records spent its early years putting out music that largely mirrored what the larger New York record companies were producing but “soon realized that there was a significant demographic that was not being served by the music that was being released, particularly Black and Southern Americans,” noted Dahan.

At a time when the major record labels were recording mostly classical and European music, Gennett made a name for itself by diving deep into the heart of the emerging American sound: jazz, blues and mountain music—what today we’d call country western.

The Gennett label was noteworthy for not only recording and promoting Black musicians at a time when few others would do so, but for promoting racially integrated musical acts as well: Jelly Roll Morton and the New Orleans Rhythm Kings marked the first interracial recording session in American music history.

“I don’t know which came first,” said Irmscher of her family’s business. “Whether they were making what people wanted to hear or if Gennett promoted them and then they became famous. I think maybe it was a little bit of each.”

Musical historians note that Gennett’s promotion of such musicians wasn’t born of a principled social agenda—it was simply business.

In addition to its work recording performers, Gennett Records opened its doors to anyone willing to pay the studio’s rate for so-called vanity recordings. The Ku Klux Klan, with its enormous influence in the area, paid to record its propaganda at Gennett. “That was a terrible time in our country’s history,” said Irmscher. “But Gennett Records never promoted [the Klan], never put them in the sales catalog.”

Walk This Way

Not much is left today of the once-mighty Gennett empire. The largest structure still standing is a long and low brick building with the Gennett Records logo emblazoned on the side of a six-story tower. This site of robust piano-making operations is now an industrial-vibed events space owned and operated by the city of Richmond.

The Whitewater Gorge Trail—a short connector to the famed Cardinal Greenway, Indiana’s longest rail-trail—loosely parallels the railroad spur that once serviced the complex, taking users right past the building and the Gennett Records Walk of Fame, a celebration of the recording artists that contributed so much to musical Americana. Resembling 78 rpm records, the 35 ceramic and bronze medallions have accompanying plaques that explain each artist’s musical achievements.

The actual recording studio is no more, but a marker notes where it once stood. For music aficionados, the lack of a building hardly diminishes the experience of visiting the site, said Kennedy. “You see the sign and you’re like: ‘Wait a minute—I’m right along a river. You’re kidding me. They made legendary records down here?’ You look straight up the gorge, and that’s where the C&O railroad train would come in. The location is just so magical.”

Richmond, Indiana

This twice-recognized All-America City of 37,000 has embraced its musical history with gusto. In addition to the Starr Gennett Foundation’s Walk of Fame, visitors will find a developing 3-mile artwork-laden walking loop throughout town and a restaurant that author Rick Kennedy calls “a shrine to Gennett.” The Firehouse BBQ & Blues, owned by firefighter Tom Broyles, is quite fittingly found in a Civil War-era firehouse. A painting of Blind Lemon Jefferson—known as the Father of the Texas Blues—adorns the exterior of the building, and inside, images abound of stars such as the Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards and the Beatles’ George Harrison, who credit Gennett recording artists with shaping their sound.

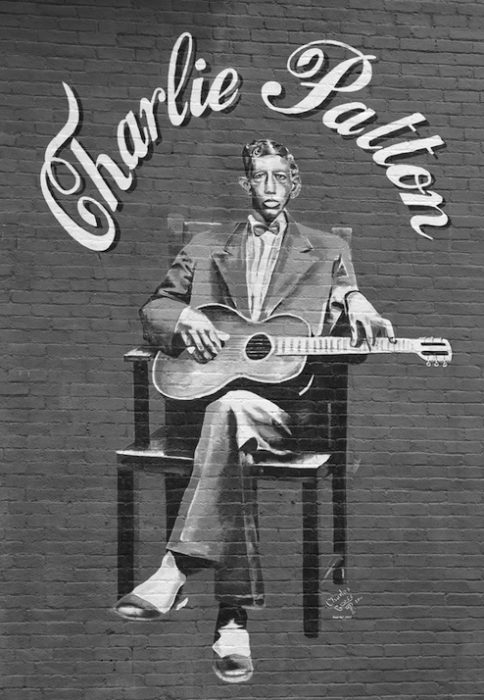

Broyles is also spearheading the Midwest Music and Heritage Trail, a work in progress to place artwork celebrating Richmond’s musical history around town. The first five pieces were recently installed, commemorating Louis Armstrong, Hoagy Carmichael, Big Bill Broonzy, Charley Patton and the Murray Theatre (at which many acts performed); the eventual goal is around 50 such markers. “There’s a lot of rich history here and it’s so cool,” said Broyles. “It’s something I don’t think a lot of people would expect.”

(Left: Medallions celebrating storied musical artists grace the Gennett Records Walk of Fame; pictured are Duke Ellington, Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver. | Courtesy Natasha Marco)

This article was written as part of History Along the Great American Rail-Trail™, a project of TrailLink.com™ highlighting hundreds of stories and historical points of interest along the 3,700-mile route. It was originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format. Republished by permission.

Posted: 28 February 2022

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , History and Culture