How an abandoned Army depot became home to some of the world’s most endangered animals

From farmland to POW camp to playground for cheetahs, the bucolic spot in Virgina that houses the Smithsonian’s Conservation Biology Institute has a past as fascinating as any object in our collections.

The property that we know today as the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, located in Front Royal, Virginia, has a fascinating history going back to occupation by Native Americans, fertile farmland, a military horse breeding station, a holding area for World War II prisoners of war, a department of Agriculture cattle station, and finally the SCBI research and conservation center, a part of the National Zoological Park. The site was transferred to the Smithsonian in 1975.

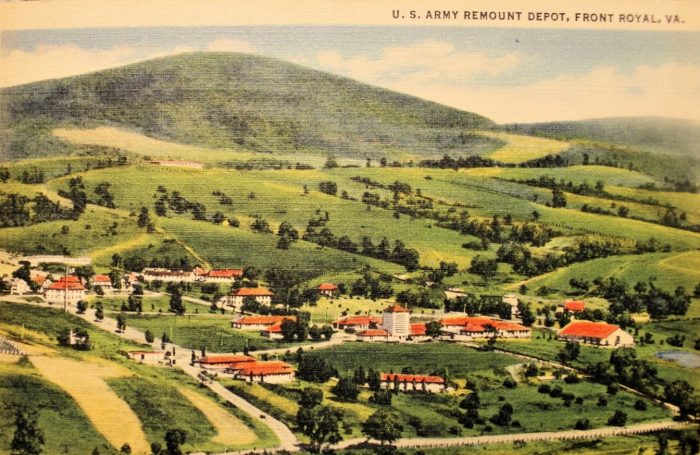

Of particular interest from an architectural history point of view is the complex of buildings that populated the U.S. Army Remount Depot from its purchase in 1910 to its close in 1948. The integrity of the campus, particularly the Central Post, seen in the postcard, as well as the surrounding landscape, was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources in 2010. A future Master Plan by the Office of Planning, Design and Construction will include a National Register nomination to document in-depth the history of the facility from earliest to modern times. The SCBI campus is currently comprised of approximately 3200 acres of research areas, animal enclosures, agricultural fields and over, 150 buildings and site features mostly constructed by the Army Quartermaster for the Remount Depot.

At the turn of the 20th century, the cavalry was in need of fast and strong horses particularly after the Spanish American War and with World War I on the horizon. The army developed a breeding program using purebred stallions and healthy mares from nearby farms. The first buildings constructed were in 1912 for colt sheds and stables, followed in 1915 by more substantial residential and administrative support facilities. The majority of buildings were for administering the functions of the remount depot, such as veterinary services, feed and hay storage barns, residential and commissary structures. Over 5,000 acres spread out from the core area for fields, ponds, exercise yards, and even other farms. The more substantial buildings were of stucco or concrete with either red clay tile roofs or red standing seam metal roofs. The walls of the buildings were of a light creamy color. The facility was self-sustaining with its own wells, septic systems, fire station, and it was close to the Front Royal rail station for transporting horse and mules throughout the country.

Since the Smithsonian ownership of the campus, the historic buildings have been sensitively repurposed for research, offices and support building. As the primary functions for SCBI are animal and ecological research, most of the extant facilities have been easily updated for continued use. Currently, the Administration Building is being revitalized and an existing veterinary hospital will shortly be updated. Many of the residential buildings are rental units for students and visiting staff and one of the larger houses has been adapted to office use. Through a partnership with George Mason University, several new and renovated buildings have complimented the existing architecture on campus.

This facility is a real asset to the work of the National Zoo and there is potential for underutilized buildings if funding is available for revitalization. While the campus is not open to the public, it is hoped in the future that the annual Discover Day in the fall can be reactivated so the public can appreciate the work of the SCBI.

Sharon Park is Associate Director, Architectural History + Historic Preservation in the Office of Planning, Design, & Construction

The author wishes to thank William Pitt, Deputy Director, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and Assistant Director of Conservation & Science, for reviews and comment on this article.

Posted: 1 November 2022