In 1904, Theodore Roosevelt Won a Presidential Election…And a Pair of Ostriches

President’s Day was last week, but we’re still celebrating the contributions one President made to the Smithsonian that resonate today.

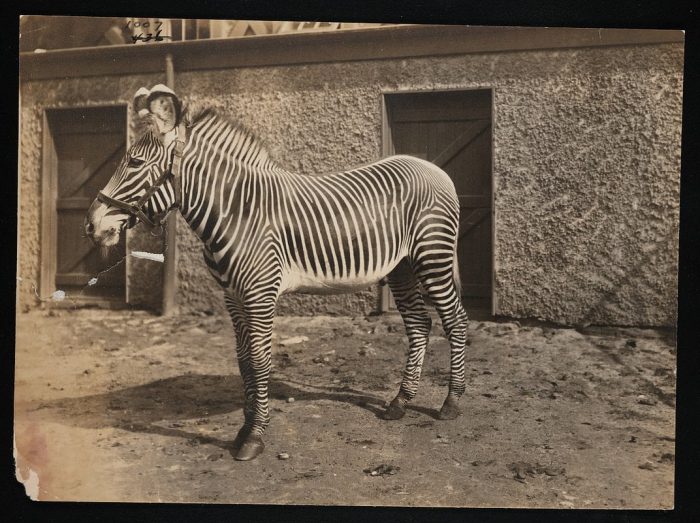

On November 7, 1904, the Atlantic Ocean liner Minneapolis docked in New York City to much fanfare. Stored in the ship’s cargo was an exotic menagerie of live animals including two monkeys, a zebra, a lioness (a second one had died en route) and a towering pair of male Somali ostriches addressed to President Theodore Roosevelt.

The animals, which hailed from the Horn of Africa, were a gift from King Menelik II, the emperor of Abyssinia (present day Ethiopia). Menelik had sent them to president Roosevelt on the eve of his first reelection bid in 1904. The site of the ostriches deboarding the boat presented quite the spectacle. The following day, the New York Times ran the headline “MENELIK’S GIFTS HERE,” and reported that the “Abyssinian monarch wanted Mr. Roosevelt to get them to-day [sic], when, Menelik hopes, Mr. Roosevelt will be elected president.” Roosevelt would soon notch a commanding victory in the election.

Roosevelt and Menelik were no strangers when it came to gift giving. In December, 1903, Menelik sent Roosevelt a letter thanking him for the two guns and typewriter the president had sent. In return, Menelik, who is remembered for repelling an Italian invasion and modernizing the region that would become Ethiopia, promised to send a pair of lions and a set of elephant tusks. He hoped to help “fortify…the friendly relations between our two countries,” which had blossomed during Roosevelt’s presidency.

In March 1904, Menelik’s first batch of gifts arrived in Boston. Among them were the elephant tusks, a lion cub named Joe and a hyena named Bill. Neither Joe nor Bill endeared themselves to the crew of the ship. According to an account published on the front page of the New York Times on March 12, 1904, the lion cub had “left the marks of his teeth on several of the crew that came near him.” The story also mentioned that “the President will have his hands full” with the hyena because the “beast laughs nearly all the time.” His second shipment of animals in November caused less of a stir as they crossed the Atlantic.

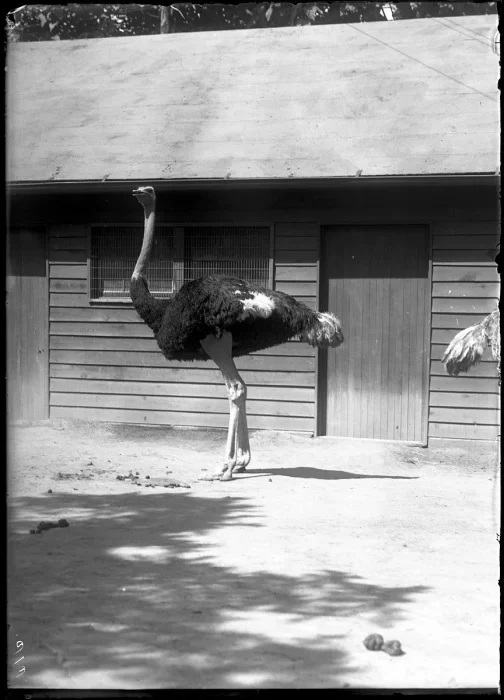

The two ostriches Roosevelt received from King Menelik, along with the zebra and lion, were bound for the National Zoological Park, where they arrived on November 24, 1904. They were among the first of several wild presidential gifts to end up at the National Zoo. Calvin Coolidge donated several animals including a raccoon and a pygmy hippopotamus from Liberia named Billy (not to be confused with Roosevelt’s hyena, Bill, who also ended up at the National Zoo) and Shanthi, a young female Asian elephant, ended up at the National Zoo after being given as a diplomatic gift from the Sri Lankan ambassador to Jimmy Carter’s family in 1977.

Menelik’s gift ostriches were not the last time Roosevelt came across these big birds. After he finished his second term, Roosevelt embarked on a Smithsonian-sponsored expedition in 1909 to eastern Africa with several prominent field naturalists. Their goal was to procure specimens for the United States National Museum, the precursor to the National Museum of Natural History. Over the next two years, the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition collected thousands of specimens, a couple of which are still on display today, including a white rhinoceros in the museum’s Hall of Mammals and a male lion and pair of shoebill storks in Objects of Wonder.

The Smithsonian expedition provided Roosevelt a chance to observe ostriches up close in the wild. In an article published in the June, 1918 edition of The Atlantic, Roosevelt mentions several instances when he came across brooding ostriches sitting on their eggs. He also made note of their “curious waltzing or gyrating,” concluding that their elaborate dancing was “calculated to attract the attention of every beast or bird that possessed eyesight.”

This firsthand experience helped make the 26th president an expert source on ostriches, the world’s largest birds. In that same Atlantic article, Roosevelt critiqued several statements made in a popular article about ostriches. He took particular umbrage with the author’s assertion that an ostrich was just as dangerous to an unprotected man as a charging lion.

By simply “lying down, he escapes all danger,” Roosevelt wrote. “In such case, the bird may step on him, or sit on him; his clothes will be rumpled and his feelings injured; but he will suffer no bodily harm.” Roosevelt concluded that someone taking a dive in front of a hungry lion wouldn’t be so lucky.

(Smithsonian Institution Archives)

One of Roosevelt’s ostriches was estimated to be around 35 when it arrived at the zoo. Remarkably, it lived in Washington for another 26 years. Due to its extremely advanced age, the giant bird had been blind for several years before it died on December 3, 1930.

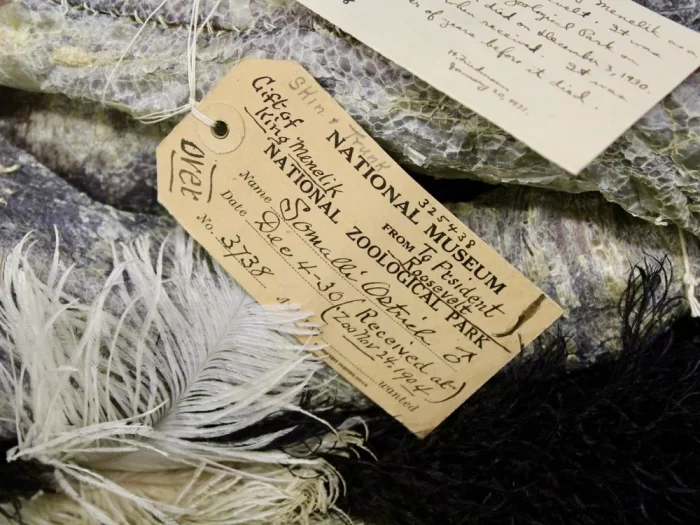

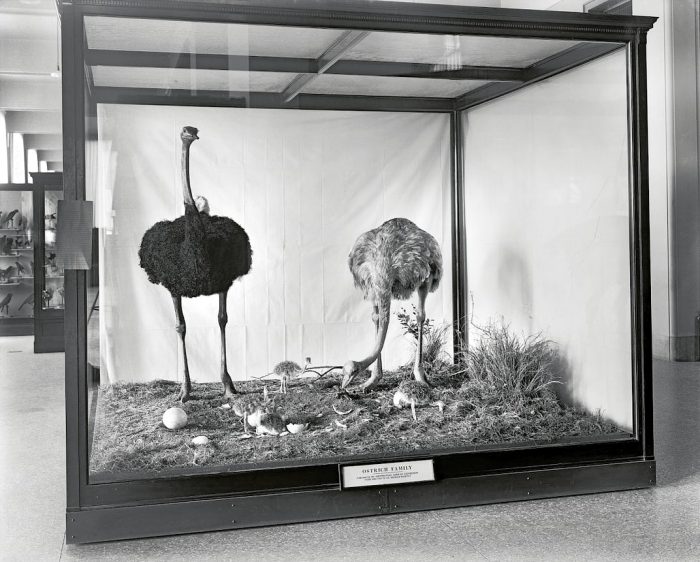

Soon afterwards, it arrived at the National Museum of Natural History. Like other specimens, it was given a number and outfitted with labels to help collection staff keep track of it within the museum’s bird collection. Its scaly skin and fuzzy, black and white plumage are deposited alongside the remains of the other ostrich Menelik sent (which died in early 1910) in a cabinet of oversized drawers housing the biggest birds the avian world has to offer.

Here, the ostrich specimens are easily accessible to researchers ranging from ornithologists to historians. As part of the museum’s bird collection, these presidential ostriches have become the scientific gift that keeps giving.

Jack Tamisiea is a Science Communications Assistant at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. In addition to covering all things natural history for the museum’s blog, Smithsonian Voices, he tracks media coverage and coordinates filming activities for the museum’s Office of Communications and Public Affairs. Jack recently completed his masters in science writing at Johns Hopkins University and his writing has appeared in the New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic and other science-focused publications. In his free time, he loves exploring the outdoors with a notebook and camera. You can read more of Jack’s work at https://jacktamisiea.com.

This article was originally published by the Smithsonian magazine blog, Smithsonian Voices. Copyright 2023 Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with permission from Smithsonian Enterprises. All rights reserved. Reproduction in any medium is strictly prohibited without permission from Smithsonian Institution.

Posted: 28 February 2023