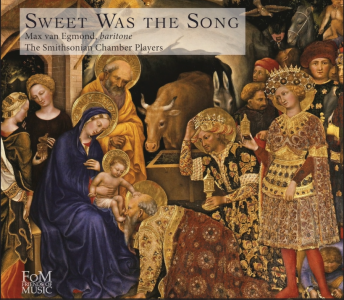

Sweet Was the Song: Ancient music for modern times

Kenneth Slowik, director of the famed Smithsonian Chamber Music Society, shares some of the history of Christmas carols as well as the history of one of the Society’s most cherished recordings.

The Adoration of the Magi, Gentile da Fabriano (1423). Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

In the late 1970s, and through the 80s, the Smithsonian Chamber Music Society enjoyed a beautifully symbiotic relationship with the now-defunct Smithsonian Collection of Recordings, for which we made four multi-record box sets of music by Bach, Handel, Mozart, and Beethoven. Each of these sets enjoyed phenomenal sales (for classical releases) of over 200,000 units, through mail order distribution. Around the holidays in 1989, Margaret Robinson, then the Executive Producer for The Smithsonian Collection of Recordings, expressed her wish that Jim Weaver and I contemplate making a record of traditional Christmas carols. I immediately thought of asking my long-time colleague, the distinguished Dutch baritone Max van Egmond, if he would be willing to collaborate on such a project. His skill with investing each word with meaning has always appealed to me, and his fame in early music circles help make the disk a success. (It was even included in a “Readers Digest France” CD compilation.)

Baritone Max van Egmond

So, in June of 1990, around the time of the Oberlin Baroque Performance Institute, or BPI, in the great hall of Oberlin’s Carnegie Library, and while temperatures outside hovered in the 90s, we recorded the album “Sweet was the Song.” The title comes from an anonymous consort song from early 17th-century England, “Sweet was the song the virgin sung when she to Bethlem Judah came.” The original consort setting, for voice and four viols, suggested my approach to the disc’s instrumentation. Relying heavily on the BPI faculty, with a few strategic imports, we were able to field a consort of viols, a consort of recorders, and an oboe/bassoon consort, adding to these a brace of violins, plus organ and virginals, a kind of rectangular harpsichord. Former New York Pro Musica wind player Shelly Gruskin was invited to join us for his skill on the “domesticated” French bagpipe, or muzette, but also proved an agile percussionist. These wide-ranging baroque instrumental colors were chosen not because they were, in the majority of cases, somehow “authentic,” but because we found them particularly pleasing timbral combinations.

I borrowed some of the arrangements, in their general design, from baroque-era sources such as Schein, Scheidt, Praetorius, Daquin, and Marais. Others were made specifically for this occasion, and have been influenced by folk and popular, as well as art music, traditions. Many benefitted from the exceptional improvisatory skills of my highly prized colleagues and collaborators on the project. It is with bittersweet pleasure that I listen, 30+ years on, to the contributions of those no longer with us: oboist James Caldwell, bassoonist Dennis Godburn, recorder player Scott Reiss, viol player Margriet Tindemans, and my Smithsonian colleague, keyboard player Jim Weaver, who was an early Covid victim.

What makes a composition a carol?

So what, exactly, constitutes a Christmas carol? The term today is applied to many kinds of festive music: Annunciation and Christmas hymns, celebratory folk and popular songs, and even the commercial music produced for secular Christmas observance. The world “carol” comes to us, via Latin and French, from the Greek word chorus (a circling dance); early medieval European carole were ringed dances in which the dancers sang the music themselves. Later, many were used in liturgical processions. The oldest surviving English Christmas songs date from the turn of the fifteenth century, around the time when the first mystery plays—ecclesiastical productions that explained biblical stories—appeared. The theatricality and loose structure of mystery plays signaled a departure from earlier Christian ritual, which had been relatively straight-laced and whose music had been narrowly circumscribed. Now myriad sources for celebratory music became acceptable. Some of the oldest carols were first used as incidental music for mystery plays. Many monophonic settings, derived from ballads, were based in minstrel tradition; others were circulated in songbooks for household use; yet others quote psalms or scripture, making them a type of hymn. A not inconsiderable number of carols, like two we’ve included here, “Angels we have heard on high” and “In dulci jubilo,” were macaronic, mixing lines of Latin ecclesiastical text with vernacular poetry. In most cases, the authors of these early carols remain obscure. The emergence of the Puritan tradition in England—including the complete abolition of Christmas celebrations in 1647—ended this first stage of carol production.

After the 1660 Restoration of Charles II, the older carols associated with church dramatics fell out of favor, though some continued to circulate as broadsides—large, single pages of music, also known as broadsheets, which were a popular medium for ballad transmission. The decline of older carols made space for the composition of new songs, both in England and on the continent. Though a great number were anonymous songs of folk origin, composers and clerics of towering stature also authored or arranged Christmas hymns. We’ve included Vom Himmel hoch by Martin Luther, and several carols arranged by Michael Praetorius.

As simple and celebratory music, carols often share features with popular songs. Text and tune are not necessarily conceived together, and many of the carols in our collection have been sung to many melodies and in many languages in the course of their use. Both carols and popular songs often intersect with folksong and national musical traditions. They frequently breach denominational boundaries, and new versions proliferate as different Christian sects develop idiosyncratic texts and arrangements.

The mid-19th century saw several concentrated efforts, many of them English, to collect and publish carols. Unlike earlier compilations, these collections mixed music from many different periods and regions of the carol’s development, and preserved folk carols that had previously been circulated orally or in ephemeral forms such as broadsides.

But despite all efforts to codify and standardize Christmas music, carols have remained protean, suitable to adaptation, translation, recombination, and arrangement.

So here’s our 1990 take on 22 of our favorite carols. There’s no video documenting the performances, but translations and a thumbnail sketch of the origins of each is included. I hope they help brighten your holidays.

Sweet Was The Song: Traditional Carols sung by Max van Egmond, baritone, with the Smithsonian Chamber Players under the direction of Kenneth Slowik (ND040). Mary Anne Ballard, viols; James Caldwell, oboe; Dennis Godburn, bassoon & recorder; Shelly Gruskin, muzette, recorders, flute, & percussion; Stanley King, oboe, oboe da caccia, & recorder; Michael Lynn, recorder; Marilyn McDonald, violin; Catharina Meints, viol; Linda Quan, violin; Scott Reiss, recorders; Alice Robbins, viol; Marc Schachman, oboe & oboe d’amore; Kenneth Slowik, viols, keyboard, & percussion; Margriet Tindemanns, viol; James Weaver, keyboard. Recorded 1990. Re-issued in France by Reader’s Digest in the series Les plus grands voix du monde, 3545.16/1.2.3, and on the Friends of Music label (in 2017) as FofM 12-025.

Click here to listen to the full recording

Artistic Director of the Smithsonian Chamber Music Society, Kenneth Slowik first established his international reputation primarily as a cellist and viola da gamba player through his work with the Smithsonian Chamber Players, Castle Trio, Smithson String Quartet, Axelrod Quartet, and with Anner Bylsma’s L’Archibudelli. Conductor of the Smithsonian Chamber Orchestra since 1988, he became conductor of the Santa Fe Bach Festival in 1998, and led the Santa Fe Pro Musica Chamber Orchestra from 1999 to 2004. He has been a soloist and/or conductor with numerous other orchestras, including the National Symphony, the Baltimore, Vancouver, and Québec Symphonies, the Filharmonia Sudecka, the Pleven Philharmonic, the Polska Orkiestra Sinfonia Iuventus, the KwaZulu-Natal Philharmonic, and the Cleveland Orchestra.

Read more about Kenneth Slowik and the Smithsonian Chamber Music Society

Posted: 24 December 2023

I shared this recording with my family and we all really enjoyed it. The music was beautiful and so different from what one usually hears and gets a little tired of by the end of the season. The history and information included in the slide show was so fascinating. too. Thank you for the seasonal gift!