Eye on Science: Watching the weather in Panama

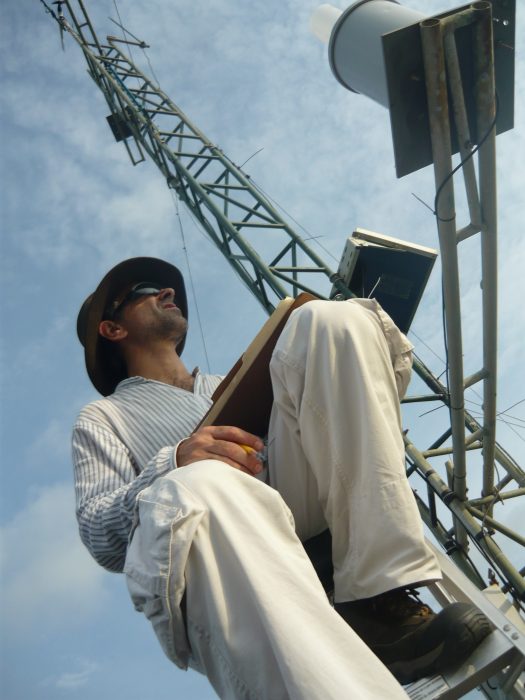

The middle of January is a nice time to plan a trip to tropical Panama. Just ask Steven Paton, who has been monitoring weather patterns in Panama for more than three decades and manages weather data going back almost a century. “I’ve been here for a lot of winters,” he told Eye on Science. He doesn’t miss the cold of his native Canada, that’s for sure. But his research contributes far more to climate science than helping tourists decide when to take a beach vacation.

Steven Paton

Steven is the director of the Physical Monitoring Program at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute based in the Republic of Panama. In a nutshell, Steven and his team continuously monitor several aspects of the weather and the ocean, such as temperatures, precipitation and sea levels, providing a solid base for a wide range of research projects and questions.

Watching the weather

The Physical Monitoring Program maintains several research stations throughout Panama, producing data that the team makes freely available to everyone. Scientists use these data to interpret their research at these sites. These data provide critical historical context, allowing scientists to look at the environmental conditions they’re seeing today at these sites and ask, “is this normal?” Steven told Eye on Science his research has been cited in hundreds, if not thousands, of publications.

On top of monitoring the weather and oceans, Steve has also been involved in studying Panama’s mangroves and biodiversity. He says that studying biodiversity in Panama, one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, is “totally amazing.”

- Spider monkey (Ateles fusciceps) Photo by Steven Paton

- Spectacled Caiman (Caiman crocodilus) Photo by Steven Paton

- Red-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis callidryas) Photo by Steven Paton

As the caretaker of such a wealth of data, Steven has recently become the news media’s go-to expert on climate change in Panama. “It started with the 1997/1998 El Niño,” he told Eye on Science. “To understand weather patterns in Panama, you have to understand El Niño, and it just snowballed from there…My name has been tied to enough stories, first about El Niño and now about climate change, that news media simply ask, ‘Can we talk to Steven about climate change?’”

Steven is up to 27 interviews during the last 12 months, but he doesn’t mind. In fact, he loves being able to help. “It’s gratifying if the Washington Post or Reuters calls and asks for me,” he said.

When asked about what it’s like to be the guy keeping the definitive record of environmental data for the Smithsonian in Panama, Steven says it’s not a walk in the park. “Getting these data, making sure it’s the highest possible quality—it’s very challenging. It’s not just sticking thermometers out and getting the temperature.” He told me it’s extremely difficult to measure the environment quickly, accurately, and precisely in a tropical environment. “Tropical conditions are very harsh to environmental sensors.” Scientists may tell Steven what type of data they need, but it has always been up to him and his team to figure out how to do it and to update and improve their methods as new techniques and equipment come around.

A dedicated team

Steven leads a dedicated team of six, whose wide range of skills, including engineering, data management, oceanography, and meteorology, have all contributed to making the Physical Monitoring Program a source of reliable data for use around the world. His team includes Sergio Dos Santos (“his engineering and data management skills have led to most of the program’s improvements during the last 15 years”), Raul Rios and Brian Harvey (“whose dedication to keeping things working in the field cannot be matched”), Alexandra Guzman (“she’s at the beginning of her career as an oceanographer. I will be sad to see her leave when she starts her master’s degree next year.”), Javier Pardo (“my newest, up-and-coming oceanographer”), and Milton Solano (“one of the top geographic information system specialists in Panama”).

Sergio Dos Santos

Raúl Ríos

Brian Harvey

Alexandra Guzman

In describing what he does with the data his team collects, Steven expressed his passion for his role. He could just collect data, publish it, and call it a day, but Steven doesn’t stop there. He tries to spot patterns and look for anomalies that he can share with the scientific community through his blog. He does this so, in the face of El Niño or climate change, he can answer the questions, “What’s going on? Is this pattern unusual? What can we expect next?” He told Eye on Science his blog is primarily read by scientists all over the world, but that many Panamanians read it, as well.

Outreach

Beyond his blog, Steven brings his data out to the public in Panama, speaking to them in Spanish, the official language of Panama. He joked that he learned Spanish because, “I was not going to allow my children to be able to talk without me knowing what they’re saying.” But truthfully, he felt that because he has been allowed to live so many years in Panama (35 and counting), he feels that he owes a debt to the country. “I like to be able to pay Panama back by communicating the science I know.”

Steven is as much known to his colleagues at STRI for his monitoring work as he is for his nature photography. His hobby started well before his time at STRI, although he says that it took off once he reached the tropics. For five years, he oversaw the photography department, and STRI gave him all the equipment he needed. Steven told me he’s not into it for money or self-promotion, because he just wants to help with STRI’s photographic needs and help promote Panama’s rich biodiversity. One of his first big projects for STRI happened around twenty-five years ago, when he teamed up with several STRI botanists and photographed almost every fruit, flower, and seed on Barro Colorado Island. Photographs from that journey are still used in presentations and scientific publications today.

- Morpho butterfly (Morpho helenor) (Photo by Steven Paton

- Leaf cutter ant (species unknown) Photo by Steven Paton

- Jaguar (Panthera onca) Photo by Steven Paton

A record of Panama’s biodiversity

When he retires, Steven told me he wants to continue to do the same type of projects for STRI and others.

Steven is in a great spot in his career right now—he said he couldn’t imagine doing anything else—but his arrival at where he is now had several twists and turns. After finishing up his master’s degree at the University of British Columbia, he felt burned out and wanted to take a break from academia. A friend at his university told him about STRI, so he wrote to several scientists until one offered him a job working with green Iguanas. But living in Panama in the late 1980s meant living under less-than-ideal conditions. “It was my first time in Latin American and nothing in nothing in my previous 26 years prepared me for what it was like to live in Panama back then,” he said. Soon thereafter, Steven says that he was lucky to get a job with the Charles Darwin Station in the Galapagos Islands of Ecuador. After a little over two years, he returned once again to Panama and STRI where he has remained ever since.

Having survived the winters of Canada, the harsh humidity of the tropics, and several years on the Galapagos Islands, Steven said that he feels that he ended up exactly where he was supposed to, and you can hear it in how he talks about his work. After 30 minutes of talking to him, we at Eye on Science could tell why STRI entrusted him with the important responsibility of managing environmental monitoring in Panama for the whole world’s benefit.

- Green iguana (Iguana iguana) (Photo by Steven Paton)

- Green heron (Butorides virescens) Photo by Steven Paton

- Garden Emerald hummingbird (Chlorostilbon assimilis) Photo by Steven Paton

You can view more of Steven’s photos on his Instagram.

If you are interested in receiving Steven’s blog posts about Panama weather and climate, contact him at patons@si.edu.

Eye on Science, our new biweekly series, will shine a light on our vast and varied body of work by bringing Smithsonian science into sharper focus. Eye on Science will tell the stories of the people behind the research, the discoveries they make and their inspiration. We will explore their passions, celebrate their contributions, and look more closely at how questions become solutions that can inform environmental policy, spur technological innovation, and promote community and collaboration across the globe.

Posted: 18 January 2024

-

Categories:

Eye on Science , Feature Stories , Tropical Research Institute