The Evolution of the American History Museum and the Curation of American Identity

As the National Museum of American History celebrates its 60th anniversary this year, Secretary Bunch reflects on how the museum has evolved along with our own understanding of history and how best to tell the story of all Americans.

On January 23, 1964, what was then the Museum of History and Technology opened its doors for the first time. Some 54,000 visitors flocked to the museum, where the inaugural exhibitions included the Flag Hall; the First Ladies’ Hall; and a suite of exhibitions on American machinery, railroads, and vehicles.

In the National Museum of History and Technology, now the National Museum of American History, the First Ladies Exhibit shows gowned figures placed in a period decorated East Room of the White House. They are from left to right: Florence Kling Harding, Grace Goodhue Coolidge, Lou Henry Hoover, Eleanor Roosevelt, Bess Wallace Truman, Mamie Doud Eisenhower, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Claudia (Lady Bird) Taylor Johnson, and Patricia Nixon. This photo was taken in 1972. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Archives

The original museum was dramatically shaped by the Cold War: its contents insisted upon American inventiveness and our technological superiority over Russia. There are pieces of the original museum, like the First Ladies’ Hall, that have endured across six decades, albeit with major changes. But as we look back over the museum’s 60 years, what strike me the most are the sweeping changes in the approach to documenting and displaying a more honest and layered history.

As a child, the National Museum of American History was among the Smithsonian museums my dad would take me to whenever we were in Washington: it was a place he promised me I could always come to learn about the world, a place where my opportunity to learn would be protected, no matter the color of my skin. That has certainly proven true over the years: I returned to our American History Museum time and again in my childhood, my adolescence, and in the beginning of my career. I learned something new each time.

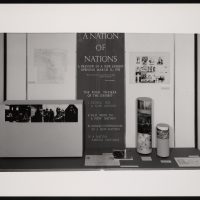

As a curator—or an aspiring curator—there are some exhibitions that stay with you: work that inspires a sense of awe you hope to emulate. For me, one of those exhibitions is Nation of Nations, which was on display at American History from 1976 through 1991. The first time I saw it was at the country’s bicentennial, which the Smithsonian marked with a Folklife Festival that spanned the entire summer. I can still remember the amazement I felt walking through the gallery for the first time.

- Monthly exhibit case in the lobby of National Museum of History and Technology, now known as National Museum of American History, featuring preview for upcoming ” A Nation of Nations” exhibition. (Photo by Alfred Harrell, November 1975)

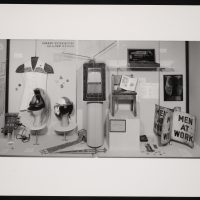

- Monthly exhibit case in the lobby of National Museum of History and Technology, now known as National Museum of American History, featuring preview for upcoming ” A Nation of Nations” exhibition, “Old Ways in a New Nation.” Photo by Alfred Harrell, November 1975

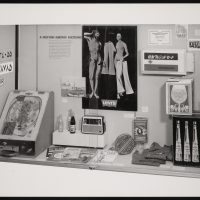

- Monthly exhibit case in the lobby of National Museum of History and Technology, now known as National Museum of American History, featuring preview for upcoming ” A Nation of Nations” exhibition, “Shared Experiences in a New Nation.” (Photo by Alfred Harrell, 1975)

- Monthly exhibit case in the lobby of National Museum of History and Technology, now known as National Museum of American History, featuring preview for upcoming ” A Nation of Nations” exhibition, “A Nation Among Nations.” (Photo by Alfred Harrell. November 1975)

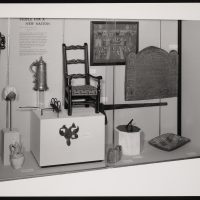

- Monthly exhibit case in the lobby of National Museum of History and Technology, now known as National Museum of American History, featuring preview for upcoming ” A Nation of Nations” exhibition, “People for a New Nation.” (Photo by Alfred Harrell, November 1975)

It was divided into three distinct sections: one that explored American immigration to 1800, which consisted of European explorers and the forced migration of enslaved Africans; another that traced the flow of immigrants in the 19th century, which increased and diversified the American populace; and finally, a section that focused on the American activities and environments shared by immigrants from the end of the Civil War to the present day. It offered up American patriotism as an exercise in celebrating diversity—a marked change from insisting upon American identity in terms of global competition. More than any other exhibition I know, Nation of Nations marked a change in how this museum—and so many other museums that took inspiration from its example—approached its responsibility to curate the public’s understanding of their history.

In the last few years of the exhibition’s tenure, another monumental gallery opened. That exhibition, Field to Factory: Afro-American Migration 1915-1940, examined the Great Migration, a movement of more than a million African Americans who moved North. It offered a rich portrayal of the hardships and the strength of community in both the rural South and in the Northern cities that absorbed an influx of people drawn to the promise of factory work and a greater sense of political and economic freedom.

When I began working at the National Museum of American History back in 1989, these exhibitions were part of what drove my work. They were reminders of how powerful an exhibition can be when it is done right: when a team of curators commits to telling a segment of history with all its complexities laid bare. Work like that inspired me to leave my own mark on this treasured museum, with the American Presidency exhibition, the redesign of the First Ladies’ Hall, and the portrayal of American history for a Japanese audience.

Entrance to “The American Presidency” permanent exhibition at the National Museum of American History

Over the course of six decades, the National Museum of American History has been entirely reinvented. It grew from a shrine to American inventiveness—a counterweight to Russian technological innovation—into a national treasure that celebrates, illuminates, and expands our American origin story. It does not shy away from the difficult truths and contradictions inherent in our mythologized history; instead, it acknowledges that the contradictions themselves make for the richest material.

I am so proud of the evolution and the excellence of this museum over the decades, and I know the next 60 years will bring about an even more engrossing vision of living history.

Do you have a favorite exhibition or memory from the American History Museum? Share it in the comments!

Posted: 31 January 2024

-

Categories:

American History Museum , From the Secretary , History and Culture