Finding the right TEMPO: Using physics for public good

For Gonzalo Gonzalez Abad of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard and Smithsonian, the most interesting part of his work is not the science itself but how we can use science to improve life on this planet.

![]() Gonzalo Gonzalez Abad has the kind of immigrant origin story that might serve him well if he were running for office. The son of two teachers, he grew up in a small village in Spain and didn’t learn English until he moved to the United Kingdom for graduate school. Wanting to work where some of the best science in the world was taking place, he sought jobs in America. He hadn’t heard of the Smithsonian before he applied for a job at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, but this year, he’s celebrating 12 years there, where he’s studying how to measure air pollution using satellites.

Gonzalo Gonzalez Abad has the kind of immigrant origin story that might serve him well if he were running for office. The son of two teachers, he grew up in a small village in Spain and didn’t learn English until he moved to the United Kingdom for graduate school. Wanting to work where some of the best science in the world was taking place, he sought jobs in America. He hadn’t heard of the Smithsonian before he applied for a job at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, but this year, he’s celebrating 12 years there, where he’s studying how to measure air pollution using satellites.

Things must be going very well with TEMPO by Gonzalo’s look of happiness while working at his Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory office in Cambridge, MA.

But Abad isn’t interested in running for office, nor in any public recognition. Despite the very public impact of his research, he prefers to be behind the scenes, doing the challenging and highly technical work needed to advance our understanding of how our behavior affects our environment.

Nonetheless, Abad has already made big news and doubtless will again as member of the science team behind the TEMPO mission, which launched a probe into space last spring to understand the sources, movements, and impacts of air pollution in North America. After a decade of development, the probe became operational last October.

So, if he’s not in it for the glory, he must do it for love, right? Actually, Abad explains, “I just wanted to do something with a social application.”

“I wasn’t initially drawn to climate research or atmospheric chemistry or satellites. In fact, I was interested in plasma physics because of its relationship to fusion energy [a method for generating clean energy].” Abad also looked into graduate programs in materials science [the study of the physical property of materials] because of its role in the development of solar cells for generating solar power.

Ultimately, he ended up working with a supervisor who was looking at how to measure atmospheric gasses using satellites. “I would have been equally happy doing anything, really,” Abad says. “More interesting to me than the science itself is the question, ‘How do we use science and technology to improve life on this planet?’”

Gonzalo in front of the Great Refractor 15-inch Telescope on the roof of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian.

After graduate school, Abad was very excited to move to the United States. He saw the US as the source of the global scientific standard. “Some of the best remote sensing science was done here, and I was always curious about the US. The US shaped the culture of the western world in the 20th century—Hollywood movies, music, etc. Countries like Spain and France have their own strong cultural heritage, but starting in the 20th century, US influence in my home country is everywhere. I was excited to learn about the source of this. For me, part of adjusting to the Smithsonian was not only learning the science, but also getting to know this cultural lighthouse of the world.

“When I started at CfA, I was just a very junior post-doc. I thought I’d stay here for two or three years and move somewhere else, as post-docs typically do. I thought, ‘People don’t stay at one institution forever.’” But when the time came, the TEMPO project was gearing up and needed more scientists. Abad secured a permanent position, and in addition to other projects, he’s been working on TEMPO ever since. “I’m glad it took so long to deploy, because it gave us a lot of time to prepare. That’s why the launch and first light turned out so well.”

Gonzalo looking puzzled at his community garden. He seems to have no clue about what he did right to get those nice-looking pumpkins. “I’m not going to be humble about those pumpkins. They were the pride of my garden last autumn. Not yet county fair size but I’m working on it.”

In his free time, Abad is drawn to music (and gardening, but that’s a story for another day.) He plays the clarinet in a band “of Portuguese immigrants.” Years ago, he was wandering around East Cambridge, when he heard music coming from a house near Symphony Hall. “I walked into Filarmonica Santo Antonio house and asked what they were playing, and whether that would let a Spaniard play with them. The group said, ‘OK, sure'” and Abad has been playing with them ever since. “I was lucky to find something that’s quite similar to Spanish culture,” Abad says. The band plays a range of musical styles, including Soussa’s marches, Portuguese music, and covers of pop singers like Lady Gaga.

If you ask Gonzalo to perform classical music at a theater in front of a crowd, he might accept that challenge, but he’s not going to hit the late-night TV talk show circuit any time soon. Abad has found his scientific happy place in his office, crunching numbers and developing conclusions about the pollutants in our atmosphere to inform the world on how to keep us breathing a little easier.

Learn more

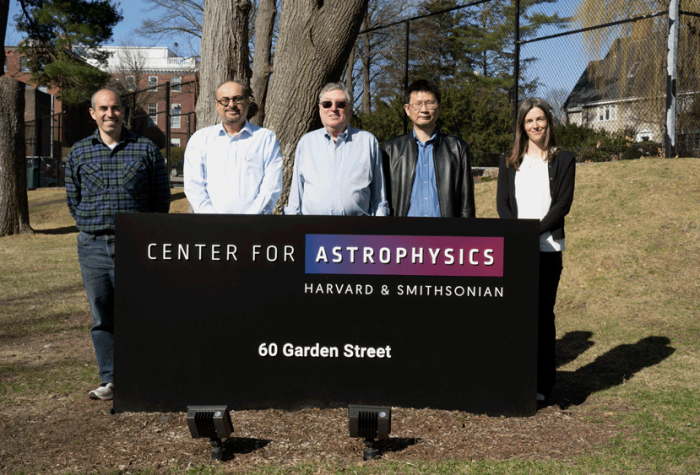

A few members of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory TEMPO team. From left to right: Gonzalo Gonzalez Abad, Raid Suleiman, Kelly Chance, Xiong Liu and Caroline Nowlan. Credit: Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

Eye on Science, our new biweekly series, will shine a light on our vast and varied body of work by bringing Smithsonian science into sharper focus. Eye on Science will tell the stories of the people behind the research, the discoveries they make and their inspiration. We will explore their passions, celebrate their contributions, and look more closely at how questions become solutions that can inform environmental policy, spur technological innovation, and promote community and collaboration across the globe.

Posted: 10 April 2024

-

Categories:

Astrophysical Observatory , Eye on Science , Feature Stories , Science and Nature