Becoming an American

It is a truism that America is a nation of immigrants, but what is the reality behind the cliché? Dr. Skorton took the opportunity to explore the concepts inherent in our democracy with a group of Smithsonian colleagues who joined him to talk about the paths they took to American citizenship.

Like many immigrants, my father loved the Fourth of July. He was born in Western Russia, now Belarus, and felt passionate about the rights Americans sometimes take for granted, such as the right to vote. I was reminded of his feelings when I invited a group of Smithsonian community members to talk about citizenship in relation to Independence Day. The nine employees and one docent, who were all born in other countries, shared their thoughts about becoming citizens, and their ideas about the Smithsonian’s goal of increased global outreach.

The participants

Pierre Commozoli is a research biologist at the Center for Species Survival, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute. Pierre was born in France to Italian parents, came to the U.S. in 2002 and became a citizen in 2011. He began work at the Smithsonian in 2002.

Pierre Comizzoli in his office on Research Hill at the National Zoo. (Photo by Ricky Carioti/The Washington Post)

Marie Dieng is an Associate Buyer for the Catalog at Smithsonian Enterprises. She was born in the Republic of Mauritius, an island nation off the southeast coast of Africa. She came to the U.S. in 1980 and started at the Smithsonian in 1987. She became an American citizen in 1990.

Marie Dieng holds the Fall 2017 edition of the Smithsonian catalogue. She began working for Smithsonian Enterprises in 1987 after emigrating to the United States from Mauritius (a small island off the coast in South Africa) in 1980.

Jelena Fay-Lukic is a museum specialist in the Archives at the National Air and Space Museum. Jelena was born in Serbia, (then part of Yugoslavia,) and came to the United States in 2003 with her American husband. She began working at the Smithsonian in 2006, the same year she became a citizen.

Tracey Fraser is director of Business Services Innovation in the Office of the Under Secretary for Finance and Administration. Tracey was born in Scotland and is a dual citizen of the United States and the United Kingdom. She became an American citizen in 2011 and began work at the Smithsonian in 2013.

Tracey Fraser was an adult when she came to the United States from Scotland. She says that having her children grow up here made her feel fully American. (Photo by John Gibbons)

Siddiki Gassama is a management support specialist in Finance and Administration at the National Zoo. Siddiki was born in Sierra Leone and came to the U.S. in 1998, when he was 10 years old. He became a citizen in 2011, the same year he began working for the Smithsonian.

Siddiki Gassama came to the U.S. as child with his family. As an adult, he strives to maintain his African roots as well as his American identity. (Photo courtesy Siddiki Gassama)

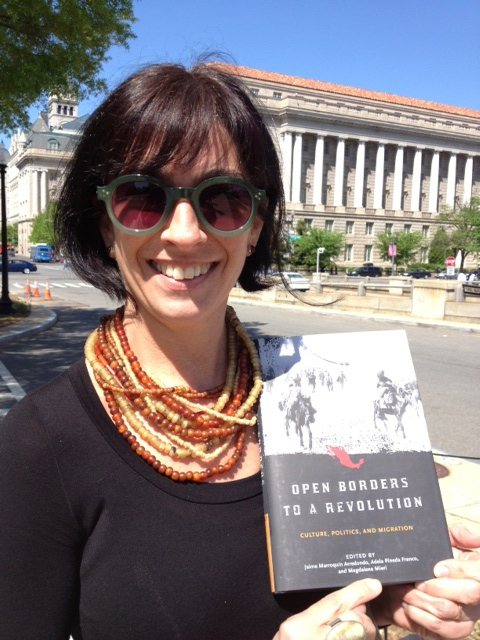

Magdalena Mieri is director of the Program in Latino History and Culture at the National Museum of American History She was born in Argentina and came to the U.S. in 1992 for an internship at the Smithsonian Center for Museum Studies. She became a citizen in 2004.

Magdalena Mieri holds a copy of a book she helped edit as part of her responsibilities directing the program in Latino History and Culture at the American History Museum.

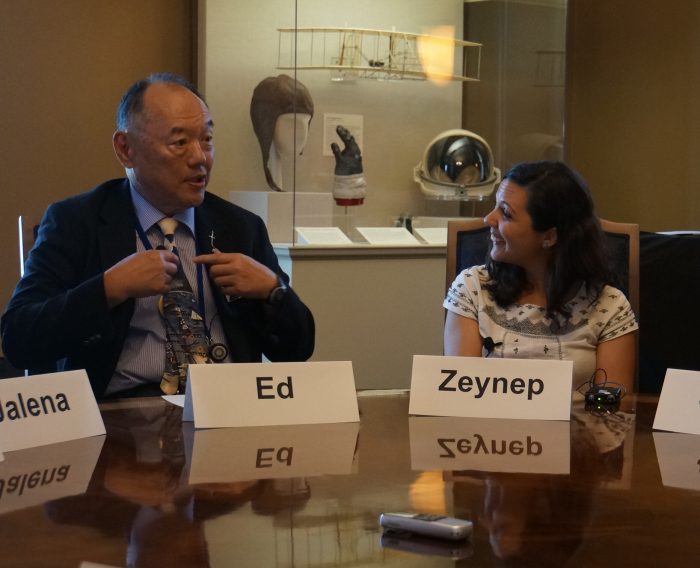

Zeynep Simavi is a program specialist for Public and Scholarly Engagement at the Freer and Sackler Galleries. Zeynep was born in Istanbul, Turkey and moved to the United States in 2009. She became a U.S. citizen in September 2014, and began work at the Smithsonian in 2011.

Hans-Dieter Sues is senior research geologist in the department of Paleobiology at the National Museum of Natural History. Born in Germany, he came to the U.S. in 1977, became a citizen in 1989 and joined the Smithsonian staff in 2004.

Hans Sues holds a cast of the skull of an oviraptosaurian. Sues and colleagues discovered the dinosaur fossil at the Hell Creek Formation in South Dakota and identified it as a new species, the so-called “chicken from hell.” This reconstruction shows the skull of Anzu wyliei, including its large toothless beak, which suggests that the species may have been omnivorous. (Photo by James DiLoreto)

Ed Tang is a volunteer docent at the National Air and Space Museum. He retired from Raytheon Corp. as a Director of Program Management for Unmanned Systems. He immigrated first from Taiwan to Canada before coming to the United States to work for Raytheon.

Zeynep Simavi listens as Ed Tang describes his journey from Taiwan to American citizenship. (Photo by John Gibbons)

Ching-Hsien Wang is a supervisory IT specialist for Collections and Digital Assets in the Office of the Chief of Information Systems She was born in the People’s Republic of China and immigrated to the United States in 1979.

Ching-Hsien Wang describes how she felt freed from a cage after arriving in the United States from the People’s Republic of China. (Photo by John Gibbons)

The conversation

Although all of the participants had very different experiences, each one of them spoke of challenges, opportunities and insights, spanning from their arrival to the present day. Ching-Hsien’s eloquent description of arriving here—“I felt I was a bird that came out of a cage and, finally, I have freedom”—energized her through the daunting process of learning English and assimilating into a culture that felt alien to her. Her experiences continue to inspire her views on cross-cultural understanding. “Western and Eastern countries have quite different cultural values and there’s a lot of misunderstanding,” she said, emphasizing that the Smithsonian can help to educate people on both sides of the cultural divide. “We need to understand them, they need to better understand us.”

Both Jelena and Marie also spoke about the struggle of learning English and, like Ching-Hsien, believe the advantages outweighed the difficulties. “For me,” Jelena said, “the proudest moment was when I received citizenship of the United States.” Having come coming from Mauritius, “an island so small you can’t even find it on a map,” Marie felt “lost” when she arrived in the United States, but was determined. “It was not easy, when my kids were born in America, from that first day, I started speaking my language . . . now they have three languages. They speak French, the French patois and English. So when they go home, they are not lost.” Having become a citizen the same year she began working at the Smithsonian, Jelena identifies with the many international visitors she encounters in her National Air and Space Museum Archives job. “I see how many people come from all over the world, to look in our collections,” she said. “I am happy to work here,” she said.

As a docent who interprets objects and exhibitions, Ed also believes the Smithsonian’s collections inspire understanding. He pointed out that “if you have intersections in artifacts to other countries, that are important to them, that is a bridge.” By emphasizing collection linkages important to international visitors, he feels we can create connections within our museums and externally, to museums elsewhere in the world. The historical, cultural and scientific content represented in exhibitions, research, programs and publications, he maintains, “that’s our leverage.”

Coming to the United States at a young age makes a difference in one’s perspective. Sidiki, who arrived in the United States at age 10, was encouraged by his parents to regularly visit his native country, Sierra Leone. “I want to hold on to my heritage and culture because America is a nation of immigrants and definitely different cultures are celebrated.” Sidiki shared that it’s important for him to use his full name, though it is difficult for some people to say. “This is an Arabic name, this is an African name . . . being an American has shown me that, hey, you can be American but also bring your heritage in.”

Having come to this country as an adult, Tracey was inspired to become a citizen through her children. “I always thought of myself as Scottish-American and they think of themselves as American-Scottish,” she told us. “It became much more important to me to understand the country they’re in” she said, adding that it’s also important to her that her children understand “where they came from.”

The value of maintaining ties to one’s native country was emphasized by Zeynep who talked about the benefits of having two cultural perspectives. She compared viewing new experiences against earlier memories to seeing things through a kind of mirror. “You start to have a different perspective of your own culture but you also bring that perspective into where you live now,” she said.

Hans came to the U.S. as an “adventurous young graduate student” but often travels back to Germany and to other countries. He feels there are multiple ways the Smithsonian can create a stronger presence outside the United States. Hans has participated in media interviews about the Smithsonian and its research in English and German, and believes communicating in other languages helps us expand our reach in a powerful way. He maintains the broad scope of the Smithsonian’s mission and its assets enhance our potential for outreach. “I think the Smithsonian is uniquely suited because of the diversity of what we do, the diversity of our people, and I think that we have a unique role in that we can mediate diversity in an international context,” he said.

Like Hans, Magdalena came to the United States to further her education. The fellowship she began at the Smithsonian evolved into a full-time position, and to American citizenship. She now helps plan naturalization ceremonies held at the National Museum of American History. She is passionate about “opening new doors to immigrants, helping them learn about American history and how this country has really been diverse from the very beginning.” It’s America’s diversity that Magdalena loves. “I learned to use chopsticks in this country. I learned to listen to Zimbabwe music in this country,” she said.

Although he originally thought becoming a citizen would be a routine, unremarkable experience, Pierre was unexpectedly moved by the ceremony. Having grown up in France, Pierre felt he knew a great deal about the United States but, after moving here, discovered stereotypes in movies and music didn’t prepare him for understanding individuals and customs. He emphasizes the importance of being truly interested in other people to understand them, their culture and uniqueness. “It’s not difficult to know each other—it requires a little more curiosity than anything else,” he said.

In one way or another, all of the participants stressed the benefits of maintaining ties to their native country. And they emphasized that diversity, particularly the kind represented in speaking different languages and understanding the values and customs of other countries, make the Smithsonian a wonderful, exciting place to work and enhance the potential we have for growth. As Pierre pointed out to me, “it’s a huge advantage that you have, as Secretary, to have us working here.”

I totally agree. I would like to thank Ching-Hsien, Jelena, Ed, Sidiki, Tracey, Zeynep, Hans, Marie, Magdalena and Pierre for sharing their thoughts with me. Our conversation was inspiring and I look forward to convening future such discussions, on topics important to the Smithsonian, with staff members and volunteers. Fostering conversations on matters of significance, both within and beyond the Smithsonian community, is a pillar of our Strategic Plan.

Back row, from left: Hans Sues, Jelena Fay-Lukic, Ed Tang, Ching-Hsien Wang, Pierre Commozoli, David Skorton. Front row, from left: Zeynep Simavi, Siddiki Gassama, Tracey Fraser, Marie Dieng, Magdalena Mieri. (Photo by John Gibbons)

You can read the full transcript of the conversation: TRANSCRIPT Becoming an American Conversation or listen to the audio at this link.

Posted: 31 July 2017

-

Categories:

From the Secretary , History and Culture , News & Announcements