Today in Smithsonian History: July 15, 1896

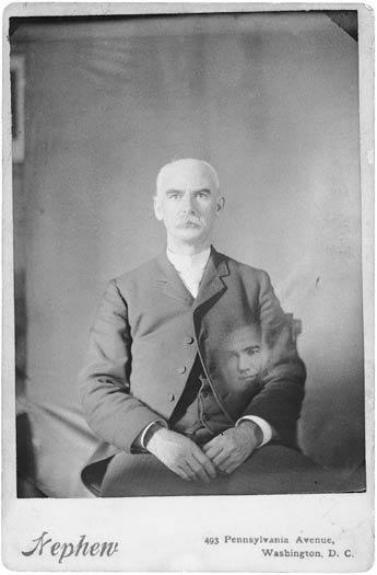

Thomas Smillie in a self-portrait with an unidentified disembodied head, 1900. Cabinet card via the National Museum of American History Behring Center.

July 15, 1896 The Section of Photographic History, Division of Graphic Arts, United States National Museum, is established with Thomas William Smillie as custodian. The first objects he collected—for the sum of $23 he bought the daguerreotype camera and photographic apparatus used by Samuel Morse, one of the first Americans to experiment with photography—were called “specimens.” A native of Edinburgh, Scotland, Smillie was hired at the age of 27 as a photographer by the Smithsonian Institution, where he worked from approximately 1869 until his death in 1917. Smillie’s duties and accomplishments as a photographer and as the institution’s first curator of photography were vast: He photographed museum installations and specimens collected by the Smithsonian, created reproductions for use as printing illustrations, documented important events, acted as a chemist for the institution’s scientific researchers, and traveled to photograph scientific research trips.

By the late 1880s Smillie’s list of photographs, either ones he made or made by others which he collected, included subjects from a growing array of disciplines: ethnological and archaeological, lithological, mineralogical, ornithological, metallurgical, and perhaps the most enticing category of all, miscellaneous. As Albert Moore, the man who sold Smillie Morse’s equipment, wrote, the Smithsonian seemed to be “making a museum of photography.”

Read more about the Smithsonian’s History of Photography Collections from the Smithsonian Institution Archives’ blog, The Bigger Picture.

This 1913 image of a photography exhibition is an example of the day-to-day documentation of Smithsonian life and work that curator Thomas Smillie and his staff regularly performed. Smillie used blue cyanotypes like this one to keep track of the glass-plate negatives his staff made, in part because the medium presented a quick and inexpensive way to create photographic prints. The bulky glass negatives were numbered and filed, and a corresponding blueprint catalogue was kept to help readily locate them.

Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives

Posted: 15 July 2019

- Categories: