Not American Indians. Not Native Americans. Just Americans.

With Columbus Day behind us and Thanksgiving on the horizon, it’s a good time to re-examine the American mythos surrounding Indians. John Barrat takes us on a tour of “Americans.”

Images of American Indians are everywhere, from the Land O’Lakes butter maiden to the Cleveland Indians’ mascot, from classic Westerns and cartoons to episodes of Seinfeld and South Park. American Indian names are everywhere, too, from state, city and street names to the Tomahawk missile. Beyond these images and names are familiar historical events and stories—Thanksgiving, Pocahontas, the Trail of Tears and Battle of Little Bighorn—that have become part of everyday conversation. “Americans,” a long-term exhibition on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, uncovers the many ways American Indian images, names, and stories infuse American history and contemporary life. Pervasive, powerful, at times demeaning, the images, names, and stories reveal how Indians have been embedded in unexpected ways in the history, pop culture, and identity of the United States.

“Americans,” which opened to critical acclaim in 2018 was curated by Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche) and Cécile R. Ganteaume.

In terms of highlights and reviews in newspapers, on TV and social media “we’ve gotten more attention for this show than possibly any project since the opening of the museum in D.C. itself in 2004,” Smith says about ‘Americans.’ “What is significant for the exhibition team, is that a lot of these reviews were very much focused on the key themes of the show. This is something we wanted and something which doesn’t always happen, particularly with an idea-driven show like this.”

“Another thing we look at in terms of metrics is how many SI units and other museums request tours from the exhibition team,” Smith adds. “We’ve had a lot of requests–staff from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum in New York City came down and were very interested in the back story of the exhibition. In terms of my career here at NMAI, ‘Americans’ has certainly been the most successful single project I’ve been involved in.”

Much of the success of “Americans,” it seems, comes from the fact that it explores Native American and American culture in a manner radically different than anything seen at NMAI before. One of the reasons for this is that early on, the curators confronted one central fact: for the majority of NMAI’s visitors and the public American Indians are a remote abstraction. Most Americans in the 21st century live in urban and suburban areas where Indians are nearly invisible.

The central gallery of the “Americans” exhibition includes nearly 350 representations of American Indians in pop culture. Paul Morigi/AP photo for the National Museum of the American Indian

“We concluded that the way forward was to show visitors that, in fact, their lives are entangled with Indians. That the United States has been built on this complicated relationship with Native peoples. To get visitors thinking about their experience here after they leave the museum ’Americans’ had to be about our visitors and the Indians those visitors knew best,” Smiths says. “We realized we had to bring the abstract Indians into the light and out in the open, to reveal how central they are to national identity and psychology.”

Consumer goods

’Americans’” opens visitor’s eyes from the beginning by submerging them in Indians Everywhere, a massive central gallery filled with Indian-themed products. Once inside it doesn’t take long to begin marveling at all the stuff sold in the United States by sticking an Indian on it. “Give your product an Indian connection and it will sell,” seems to have been the marketing mantra for a dizzying array of products during the last century.

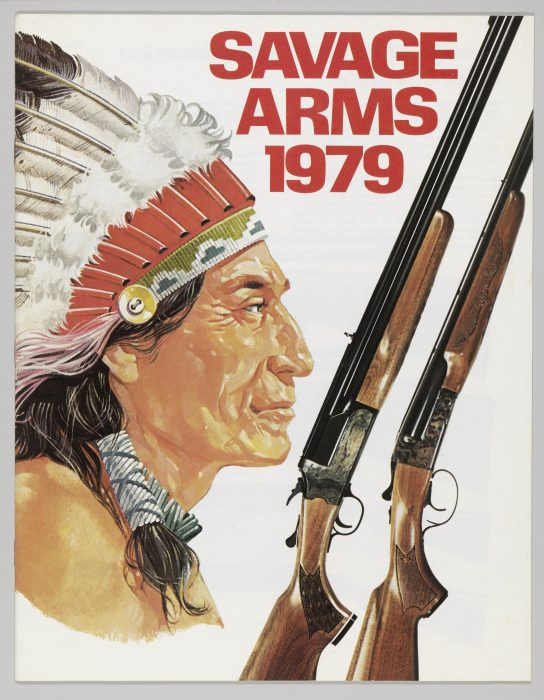

According to Savage Arms company history, its logo was the result of a deal in 1919. An Indian chief named Lame Deer negotiated a discount for rifles. In return he offered his tribe’s endorsement and an Indian-head logo. Savage Arms catalog, 1979. Savage Arms catalog, 1979. Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian.

The gallery proves that American consumers have a strong connection to Indians which the makers of of cigars, flour, guns, laxatives, apples, beer, motel rooms, sports teams, dolls, movies, brake fluid, baking powder, airlines, shoes, whiskey and much more, have been taking to the bank for decades.

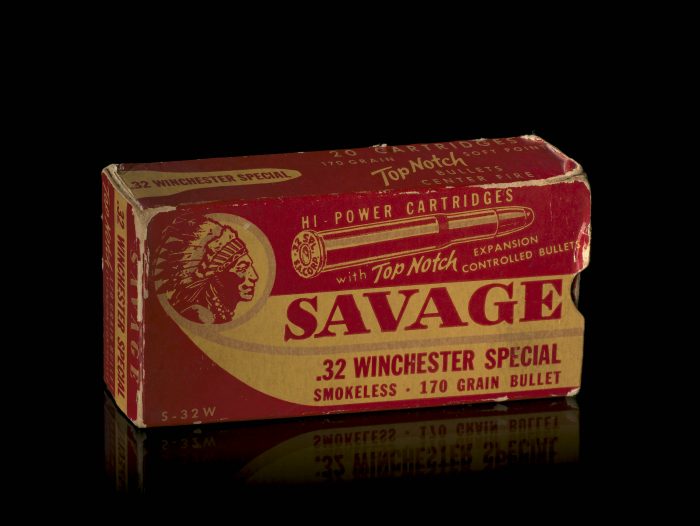

Things aren’t always what they seem. Savage Arms, whose guns are widely used in police departments, is named after its founder, Arthur Savage. Savage Arms bullet box, ca. 1950.

National Museum of the American Indian

Yet, a closer look at all the products in the Indian’s Everywhere gallery brings a deeper realization, explains Cécile Ganteaume.

“American Indians are essential to American identity, and American self-conception is bound to American Indians. These images are the tip of an iceberg and the massive structure underneath is this history that America and American Indians share and that has shaped the country and really made Americans who we are.”

Battle of the Little Big Horn

After gazing at dozens upon dozens of colorful product labels in Indians Everywhere, the majority featuring native men in eagle-feather headdresses, visitors encounter an actual Lakota eagle-feather headdress from South Dakota (ca. 1880) in a side gallery centered on the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

“Very few Lakota men ever earned the honor of wearing the wapaha, or eagle feather headdress,” its label reads. “For a man to wear one, his elders and peers had to see in him fortitude, generosity and bravery.” These headdresses also were worn only by members of Great Plains tribes and never while hunting or in battle.

Plains Indian objects on display in the Battle of Little Bighorn gallery of the “Americans” exhibition at Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Paul Morigi/AP Images for National Museum of the American Indian

The disparity is shocking. To move consumer goods, America’s advertisers placed a feather headdress on every Indian’s head, women included, no matter what region they represented or what they were doing. In reality, the exhibit reveals, few Native men ever earned the honor of wearing one.

The gallery goes on to illustrate in detail how the Lakota warriors who defeated General Custer and the U.S. 7th Cavalry at Little Bighorn later became celebrities performing in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, and their images came to represent valor, freedom and skilled combat.

“Objects in this section allow visitors to appreciate how very little the stereotype has to do with Plains Indian peoples—and how much it has to do with America’s own myth of the Wild West and need for a formidable foe,” Smith explains.

Pocahontas

A second gallery is devoted to Pocahontas (1596 – 1617) whose legacy is examined through artifacts, images and facts. Although she died more than 400 years ago, today Pocahontas enjoys a level of fame shared by just a handful of women, such as Cleopatra and Joan of Arc, who have captured the world’s imagination.. She has been a constant presence in American life since before the United States existed.

This Squaw Brand canned peas label features a woman and her infant. Native American women are commonly featured in advertising as the gatherers of food. The Centerville Canning Company was using this dated imagery to convey “fresh.” Squaw Brand Choice Sifted Peas label, 1920s. Original label part of a private collection. Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian

A large part of her influence comes from the fact that “Pocahontas put a human face on the indigenous peoples of the Americas for Europeans,” Ganteaume explains.

“Prior to Pocahontas, Europeans throughout the 1500s thought of American Indians as being less than human. When Pocahontas went to London, they recognized her as a human person. They recognized she was the daughter of a powerful leader, they recognized that she had been abducted by the English; they recognized that she had converted to Christianity and married an Englishman; she made a transatlantic voyage and was feted in the court of King James twice. They could relate to her as a human being. She is the first Indigenous person of the Americas that an amazing number of Europeans knew by name. She put a human face on the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. That is her importance.”

Considered the most stylish of mass-produced motorcycle models, this 1948 Indian Chief is on view as part of the “Americans” exhibition. Photo by Matailong Du

Four centuries later her power is undiminished. Her extraordinary life embodies the promise, peril and dilemmas of the early 1600s, all of which are spelled out in “Americans.” Pocahontas is still in our heads and the meaning of her life is still debated by her descendants, the state she helped create and the country itself.

Indian Removal Act

A third gallery in “Americans” confronts the Indian Removal Act of 1830, how it deeply divided the citizens of the United States, intellectually and emotionally.

Signed into law by President Andrew Jackson it called for moving all American Indians in the Southeast U.S. to a region west of the Mississippi. Jackson regarded Indians as inferior to whites and lacking in intelligence, industry, moral habits, and the desire for improvement. As such, “they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear,” Jackson believed.

“One of the points that we really want to get across by focusing on the 1830 Removal Act, is that this act actually envisioned a United States without American Indians,” Ganteaume says. “It called for the removal of Indians east of the Mississippi River from within the settled borders of the United States, westward.

“We want our visitors to understand what an incredible concept this is and so in the exhibition we conceptualize that removal act within the national debate that happened.”

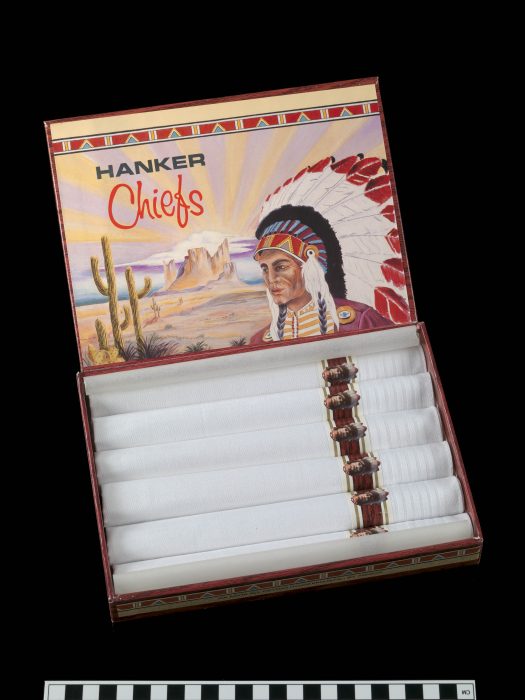

Get it? Some people thought this was hilarious. Hanker Chiefs box, ca. 1982. Gift of Lawrence Baca, 2015.

Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian

One key way the exhibition does this is through the voices of American citizens who were caught up in the moral turmoil created by the Act. For example, Christian missionary Jeremiah Evarts (1781-1831) deemed it unethical to seize the lands of the Indians, a move that would shame the United States by turning the many treaties it had signed in good faith with Indian tribes to “mere waste paper.”

Attorney and New Jersey Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen (1787-1862), also argued against removal, since Indians were living responsibly under strong patriarchal governments that were based on morality and ethics when whites first encountered them. “Our ancestors found these people…exercising all the rights, and enjoying the privileges, of free and independent sovereigns of this new world,” he wrote.\

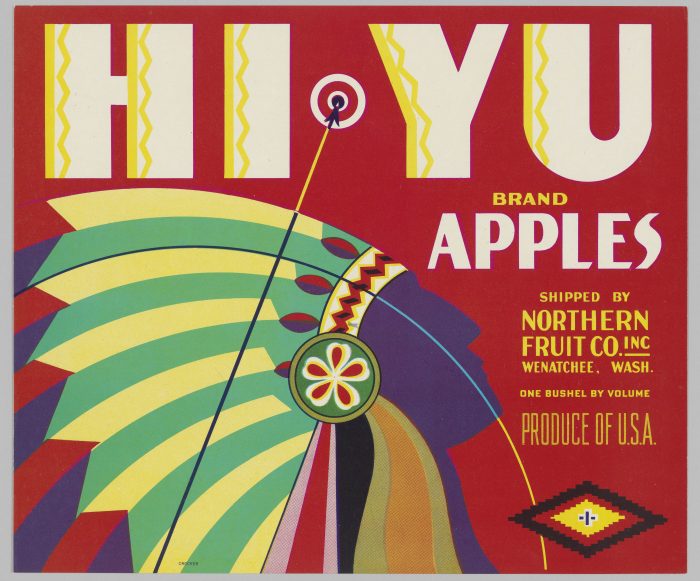

Before they were replaced by cardboard boxes in the 1960s, wooden boxes bearing colorful designs were used to ship fruit and vegetables. Often the labels featured Native American motifs. Hi Yu was the name of a brand of apples shipped from Wenatchee, Washington. Original label part of a private collection. Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian.

Many U.S. citizens favored removal, believing separating Indians from whites was for the Indians’ own good. Following the bill’s passage, the removal of Indians from the Southeast U.S. dragged on for 28 years, a sorrowful time known by the Cherokee as the Trail of Tears. This vast national project reshaped our entire country. Despite extreme hardship, native nations rebuilt in Indian territory and against all odds, are thriving today. The trauma of their removal however, remains central to their identity.

“The stories of Pocahontas, the Indian Removal Act and the Battle of the Little Big Horn are about us, all of us, Indians and everybody else,” explains American Indian Museum Director Kevin Gover. “In this exhibition we look at these events in their larger historical significance. We want to understand the historical forces, the national historical forces and sometimes the global historical forces, that led to these events. We’re looking at how Americans were caught up in these events, how they got lodged in national consciousness, how they continue today, and how they emerge to manifest themselves in popular culture.”

Theodor Geisel, who would later be known as Dr. Seuss, created the cartoon character Chief Gansett in the 1940s for the Narragansett Brewing Company. The character was used in an advertising campaign, but it never appeared on a beer bottle. Chief Gansett beer tray, 1940s. Property of Narragansett Beer. Photo By Carly Brunault

These stories are featured in ”Americans” because they “have unique staying power,” Gover adds. “Each generation of Americans decides all over again what the events mean. History keeps changing because Americans keep changing it. Americans still debate the meaning of Little Bighorn because we are still coming to grips with how the West was won.”

One factor in “Americans” appeal is that it is filled with little-known facts throughout. For example, the Indian nations removed to the west under the Indian Removal Act—Cherokee, Chickasaw, Muscogee and Choctaw—had adopted slavery as had their white neighbors in those states where it was legal. Slavery was thus established in Indian Territory (Present-day Oklahoma) after the removal.

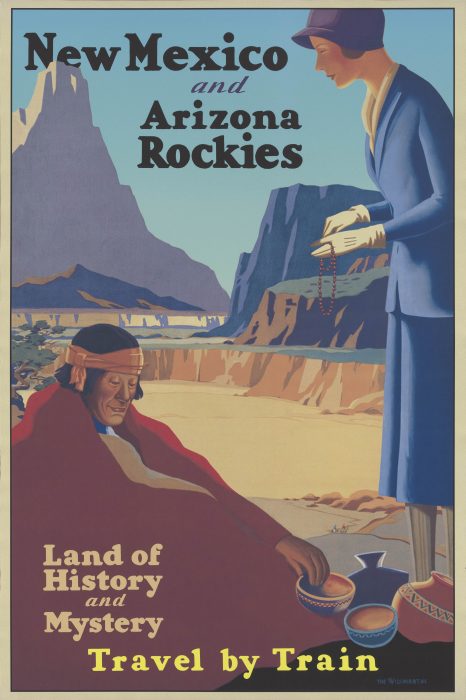

This poster was created to promote the Union Pacific Railroad and to encourage vacationers to explore the “history and mystery” of the Southwest, especially “authentic” Native American trade goods. New Mexico and Arizona travel poster, ca. 1925. New Mexico and Arizona travel poster, ca. 1925. Courtesy National Museum of the American Indian

Another subtle key to the exhibit’s appeal, Smith reveals, is its conversational tone and ability to convey complex ideas in clear language. “All text went through lengthy editing and revision by the exhibition team. The language is direct and disarming, with elements of whimsy, surprise and humor. It expresses difficult truths about the country without distancing the reader.”

One example of this is in another small side gallery that sums up the exhibition and asks for visitor feedback.

“Once upon a time Indians were the Americans,” we learn: “Soon after Europeans arrived, they called the New World America. And they called the original inhabitants Americans. Not American Indians. Not Native Americans. Just Americans.

This exhibition is titled Americans because the very name first meant the people who originally lived here.”

“Americans” is on exhibit through 2022 at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. The American Alliance of Museums honored the exhibition with its “Overall Excellence” award in 2018

Posted: 17 October 2019

-

Categories:

American Indian Museum , Education, Access & Outreach , Feature Stories , History and Culture