Arsenic and old books

“De animalibus insectis” is now kept safely under wraps.

It was while reading a University of Southern Denmark blog post in June 2018 “How we discovered three poisonous books in our university library,” that Alexandra Alvis, a Smithsonian Libraries Reference Librarian at the National Museum of Natural History, had a sudden revelation: “I recognized a book mentioned in the blog as similar to one that we had,” she recalls. “De animalibus insectis from the Joseph F. Cullman 3rd Library…one of my favorite books to pull out and show tour groups because it has manuscript waste on its cover. It illustrates a really interesting story of book production and the reuse of text.”

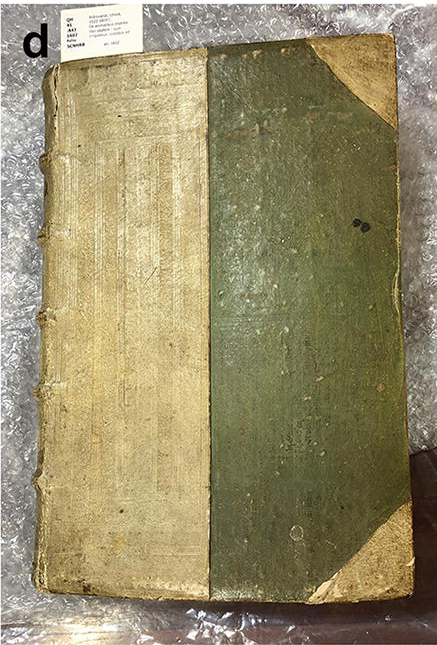

Pictured in the Danish blog was a near identical copy of the volume with its distinctive half-cream, half-green cover. Analysis in Denmark with X-ray fluorescence revealed high levels of the poison element arsenic in the green paint on the book’s cover.

After reading the blog Alvis walked into the Cullman Library stacks and, using disposable gloves, pulled out Ulisse Aldrovandi’s 1602 De animalibus insectis, and wrapped it in plastic and bubble wrap. She then called Gwénaëlle Kavich, a conservation scientist at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute, who came and examined the book in the library with an X-ray fluorescence device. Her analysis revealed that indeed, the Smithsonian’s Aldrovandi book also had high levels of arsenic in its cover.

Last November, Alvis and Kavich were among multiple co-authors of a research article in the journal Heritage Science about arsenic in this and other rare books. Smithsonian Libraries Conservator Vanessa Haight Smith and Kimberly Harmon, an industrial hygienist in the Smithsonian’s Office of Safety, Health and Environmental Management, were also co-authors as were a number of staff from the University of Southern Denmark.

John Barrat recently spoke with Alvis about this poisonous old tome.

Where is the arsenic located on this book?

The publisher pasted recycled vellum from an older medieval manuscript to the wooden board covers that are strung onto the structure of this book. Vellum is animal skin and is very strong. It is in the same family as leather but because of a different tanning process it is much thinner and easier to write on.

Recycling bookbinding material in this way was once a common practice to lower costs and make a book more affordable. To hide the characters on the recycled vellum, the bookbinder painted over them with a thick layer of green paint containing arsenic.

Green paint containing arsenic was used to paint over the recycled vellum of the book’s cover.

After the presence of arsenic was confirmed what did you do?

At first it was like ‘what are we supposed to do with this?’ Because it is a book and not technically a museum object, it first went to our conservators. They contacted the Smithsonian’s Office of Safety, Health and Environmental Management. Kimberly Harmon from that office did air testing in the library to make sure we weren’t breathing in airborne arsenic particles. She placed the book under a fume hood to make sure everything was in a neutral environment and made her recommendations to us based on that.

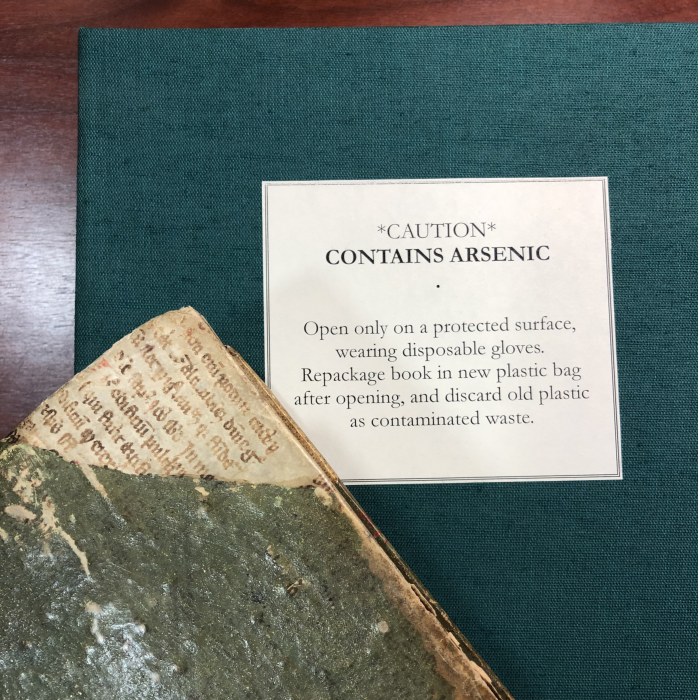

The book now is in plastic envelope in a nice linen covered non-acidic box. It’s a special enclosure made by our conservators with a warning on the cover that reads: ‘CAUTION CONTAINS ARSENIC. Open only on a protected surface, wearing disposable gloves. Repackage book in new plastic bag after opening, and discard old plastic bag as contaminated waste.’

Did you wear gloves before when you pulled this book out for visitors?

No, at the Smithsonian Libraries we do not use gloves when handling rare books, with very few exceptions. Gloves reduce manual tactility and dexterity. In movies and documentaries, you often see librarians handling old books with white cotton gloves. That is not good practice. We don’t do that here. Instead we have clean dry hands– except when handling photographic material, metal and poison.

Alexandra Alvis is a little more careful these days when sharing one of her favorite books from the Cullman Library. (Photo by John Barrat)

Were you alarmed that you had handled this book with your bare hands?

A little bit. I was shocked and I kind of thought about a cold I had a little bit ago. Was it because I had arsenic poisoning?

If a researcher showed up today would she or he be able to pick this book up and examine it closely?

Not with bare hands. But we do have the materials, such as gloves, that would allow someone to safely handle it and look at it.

I noticed other copies of De animalibus insectis have been digitized and are available online. Is there any reason a researcher would need to examine this particular volume in the Cullman Library rather than a different online copy?

Yes and no. The thing with rare books and what we often like to say is that there are no duplicates, there are multiple copies. In the hand-press period of book publishing, which is roughly before 1840, every aspect of a book was made by hand. This is why you see so many old books with different covers. They all have different quirks to them.

Because everything was made by hand, mistakes can be made, things can be inked a little bit differently, things can be set in the bed of the press wrong… So, if you are studying this book as an object and you are making a comparison across many copies, then you would need to examine this particular book in person. It is the same if you are looking at structural things, such as ownership marks, looking at provenance, things like that.

Rare books can be very unique. If you scan one you don’t necessarily have a good picture of every existing copy.

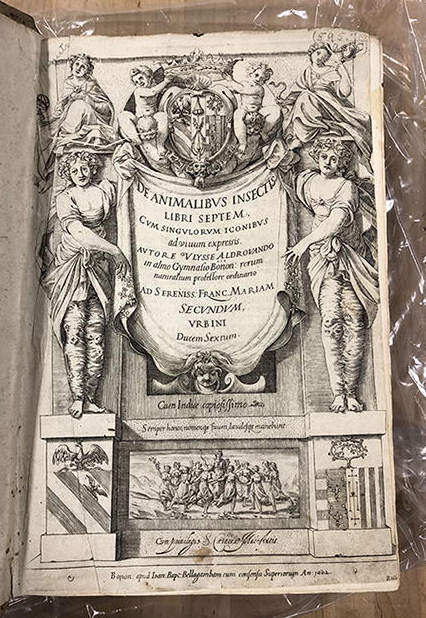

The frontspiece of “Animalibus insectis” published in 1602.

Does Smithsonian Libraries intend to have the Cullman Library edition of De animalibus insectis digitized?

That is the plan. We are not sure when that will happen and how, but that would be really the ideal outcome of this. Just so that way it cuts down even more on handling.

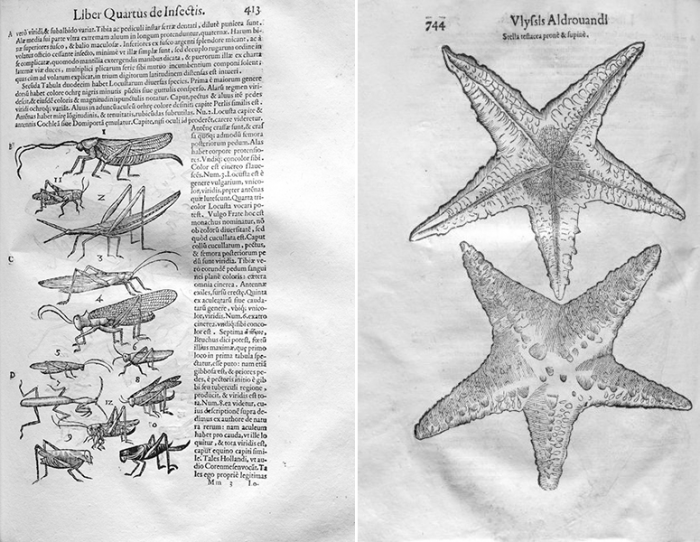

You mentioned in your SI Libraries blog that De animalibus insectis was the first European work dedicated solely to the natural history of insects. In an online version I noticed a number of illustrations of starfish in the book. What’s the story with that?

That’s a fun little quirk of 17th century science. In 1602 they weren’t quite sure what things all were, so they were kind of putting invertebrates in with other invertebrates…a starfish has more than four legs so maybe it should go in with other things that had more than four legs like insects.

This book is mostly insects and what were considered to be insects at the time. It was pre-Linnaean and his binomial nomenclature system, and it was the Wild West of naming species. Every species had a really long multiple word Latin name, and sometimes they had multiple names because different people were naming them. When Linnaeus published Systema Naturae in 1735, he kind of brought the whole field together and standardized things. Ulisse Aldrovandi, the author of this book, wrote it before Linnaeus published Systema Naturae.

Is a starfish a bug or a fish? Early scientists were pretty sure it wasn’t a star.

Has this experience raised your eyebrows about other books in the Cullman Library?

Yes, and my suspicions have been confirmed in at least one other set of books: Ludwig Emmerling’s Lehrbuch der Mineralogie, bound in 1799. It is interesting because this two-volume set contains a different kind of arsenic. This was printed in a period where a pigment called Scheele’s green or Paris green was being manufactured and it showed up in everything from clothing to candy. I called Gwénaëlle, and sure enough, her X-ray flourosope showed these books also are arsenical.

On these books the fore edges of the pages–the outer edges– are painted bright green. So, every time a reader turns a page, he or she is potentially sending arsenic particles into the air.* These books are now on lockdown. I have an ongoing list of other books I am suspicious of, and will likely call Gwénaëlle in again for testing in 2020

*Ed.note. Imagine the poor researcher who licked his finger each time he turned the page.

Posted: 15 January 2020

-

Categories:

Collaboration , Feature Stories , History and Culture , Science and Nature

So Umberto Eco wasn’t that far off…