Turning mourning into meaning

Transform the grief and despair that still lingers from the loss of Martin Luther King Jr by honoring his legacy on a national day of service.

Mourning the death of Martin Luther King Jr.

The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4, 1968, dashed the hopes of black Americans for the commitment of white America to racial equality. White Americans respected him more than other black leaders, but his opposition to the Vietnam War infuriated many. His continued insistence on nonviolent protests frustrated black activists. But in 1968 he still led the struggle for civil rights. “The murder of King changed the whole dynamic of the country,” recalled Black Panther Kathleen Cleaver.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

The New York Times wrote: “Dr. King’s murder is a national disaster.” President Lyndon Johnson declared a national day of mourning and lowered American flags to half-mast. Many white Americans were saddened or appalled; others felt untouched by the murder and some actually celebrated, calling King a “troublemaker.” King’s funeral in Atlanta drew leaders from around the world. Later, President Johnson pressured Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1968 in tribute to King’s work.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of Anthony Decaneas, Decaneas Archive, and Ernest C. Withers Trust, © Ernest C. Withers Trust

This excerpt from the PBS documentary “1968: The Year that Shaped a Generation” recounts the last days of Martin Luther King and documents the fall-out from his assassination.

The aftermath of King’s assassination

Responses to King’s death varied. Black Americans were devastated, pained, and angered. Violence erupted in more than 125 American cities across 29 states. Nearly 50,000 federal troops occupied America’s urban areas. Thirty-nine people were killed and 3,500 injured. These uprisings produced more property damage, arrests, and injuries than any other uprising of the 1960s.

Violence in Harlem was minor, due in part to New York mayor John Lindsay’s cooperation with militants, gang leaders, and youth organizers.

(left) Firefighters battle a store fire set off during riots in Harlem, New York City, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., April 1968.

©Bettmann/CORBIS

“When [America] killed Dr. King last night she killed the one man of our race that this country’s older generation, the militants and the revolutionaries, and the masses of black people would still listen to.”

Stokely Carmichael, 1968

On H Street, N.E., in Washington, D.C., only storefronts remain standing. Twelve hundred buildings burned, 12 people died, and over 6,000 were arrested while 14,000 federal troops occupied the city for six days during riots following King’s assassination, April 5, 1968.

Matthew Lewis/The Washington Post via Getty Images

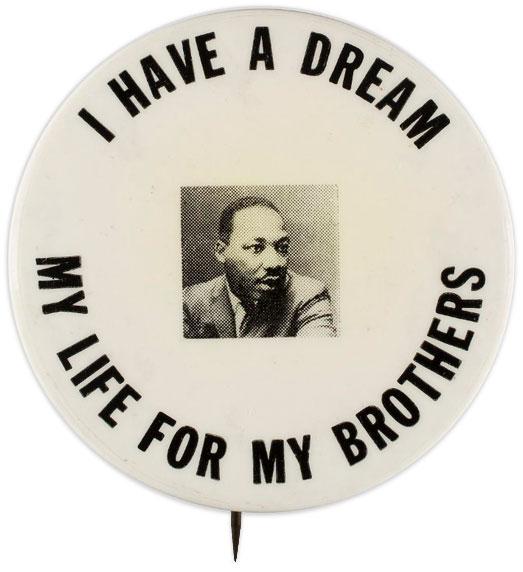

Individuals across the political spectrum displayed memorial buttons and other memorabilia expressing their sorrow and commitment to achieving King’s dream of a just and equal society. 2012.159.11

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

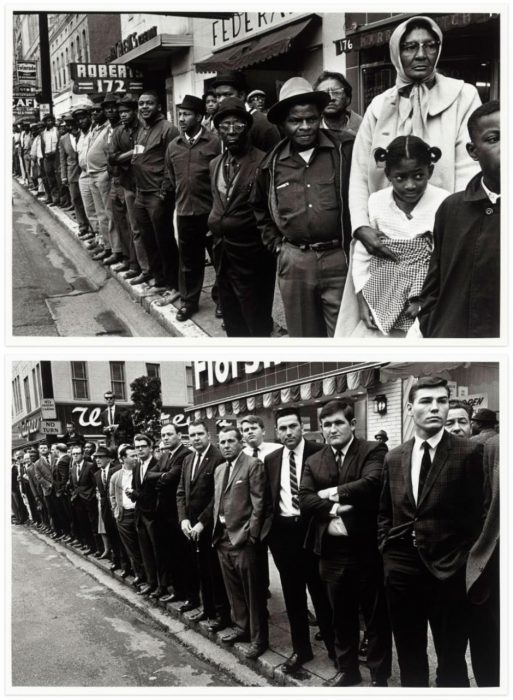

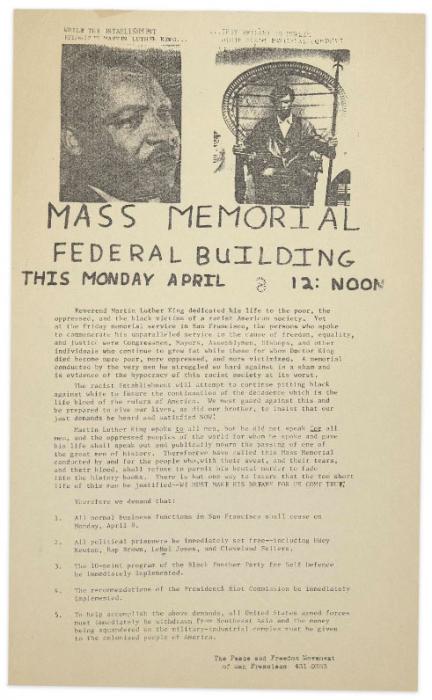

The planners of this April 8 event honored King’s commitment to “the poor, the oppressed, and the black victims of a racist American society.” Thus, they demanded that American armed forces be withdrawn from Southeast Asia, all political prisoners be freed, and that the Black Panthers’ program of radical social reforms be implemented.

This handbill announces a mass memorial for Martin Luther King, Jr. and features images of King and Huey P. Newton at the top.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

The meaning of King’s death

King’s death energized the Black Power Movement. Black Americans felt even more distrustful of white institutions and America’s political system. Membership in the Black Panther Party and other Black Power groups surged. Local organizations grew into national networks. The number of black soldiers in Vietnam supporting Black Power increased dramatically. Polls revealed that some white Americans expressed support for King’s goals, but many remained unmoved.

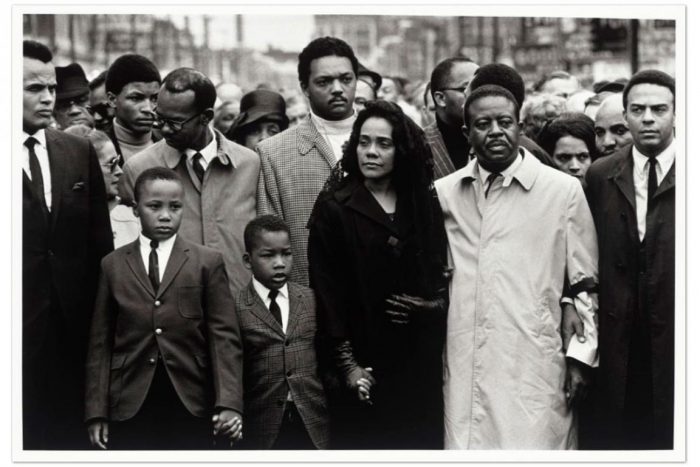

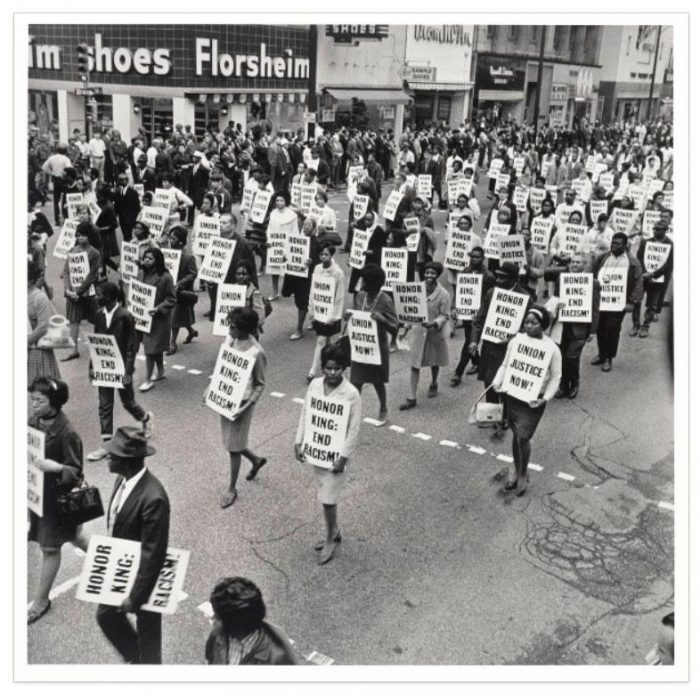

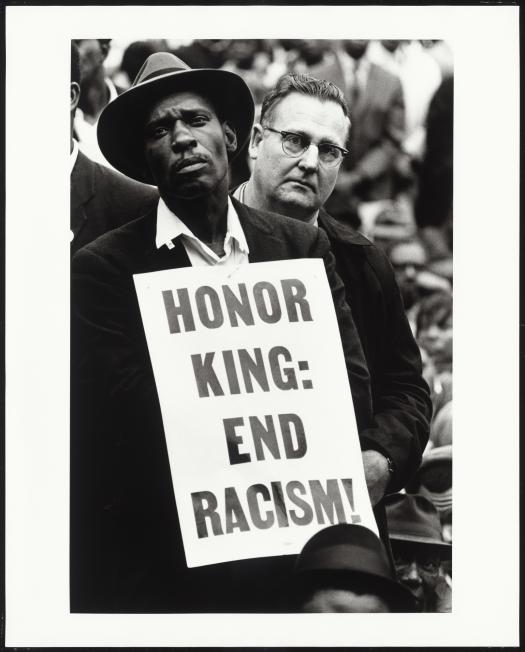

Thousands of supporters attended the memorial service for Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis on May 2, 1968, to launch the Poor People’s Campaign in honor of King’s final dream. Coretta Scott King and Ralph Abernathy, King’s closest friend and successor as president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, launched the Freedom Train , the first caravan of the Poor People’s Campaign.

© 1968 Time, Inc.

From the Collections of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, © Burk Uzzle

In 1975, the federal government designated the third Monday in January as a day to celebrate the Civil Rights leader’s life and legacy. Observed as “a day on, not off,” Martin Luther King Day is the only federal holiday designated as a national day of service to encourage all Americans to volunteer to improve their communities.

Coretta Scott King said this of Martin Luther King Day “It is a day of interracial and intercultural cooperation and sharing. No other day of the year brings so many peoples from different cultural backgrounds together in such a vibrant spirit of brother and sisterhood. Whether you are African-American, Hispanic or Native American, whether you are Caucasian or Asian-American, you are part of the great dream Martin Luther King, Jr. had for America. This is not a black holiday; it is a peoples’ holiday. And it is the young people of all races and religions who hold the keys to the fulfillment of his dream.”

This is an edited version of content originally published by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Posted: 17 January 2022