She’s a grand old flag

The original Star-Spangled Banner, the flag that inspired Francis Scott Key to write the song that would become our national anthem, is among the most treasured artifacts in the collections of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

Quick facts about the Star-Spangled Banner

- Made in Baltimore, Maryland, in July-August 1813 by flagmaker Mary Pickersgill

- Commissioned by Major George Armistead, commander of Fort McHenry

- Original size: 30 feet by 42 feet

- Current size: 30 feet by 34 feet

- Fifteen stars and fifteen stripes (one star has been cut out)

- Raised over Fort McHenry on the morning of September 14, 1814, to signal American victory over the British in the Battle of Baltimore; the sight inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner”

- Preserved by the Armistead family as a memento of the battle

- First loaned to the Smithsonian Institution in 1907; converted to permanent gift in 1912

- On exhibit at the National Museum of American History since 1964

- Major, multi-year conservation effort launched in 1998

- Plans for new permanent exhibition gallery now underway

Making the Star-Spangled Banner

In June 1813, Major George Armistead arrived in Baltimore, Maryland, to take command of Fort McHenry, built to guard the water entrance to the city. Armistead commissioned Mary Pickersgill, a Baltimore flag maker, to sew two flags for the fort: a smaller storm flag (17 by 25 ft) and a larger garrison flag (30 by 42 ft). She was hired under a government contract and was assisted by her daughter, two nieces, and an indentured African-American girl.

Mary Pickersgill, nearly forty years after she made the flag. Courtesy of Pickersgill Retirement Community.

The larger of these two flags would become known as the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Pickersgill stitched it from a combination of dyed English wool bunting (red and white stripes and blue union) and white cotton (stars). Each star is about two feet in diameter, each stripe about 24 inches wide. The Star-Spangled Banner’s impressive scale (about one-fourth the size of a modern basketball court) reflects its purpose as a garrison flag. It was intended to fly from a flagpole about ninety feet high and be visible from great distances. At its original dimensions of 30 by 42 feet, it was larger than the modern garrison flags used today by the United States Army, which have a standard size of 20 by 38 feet.

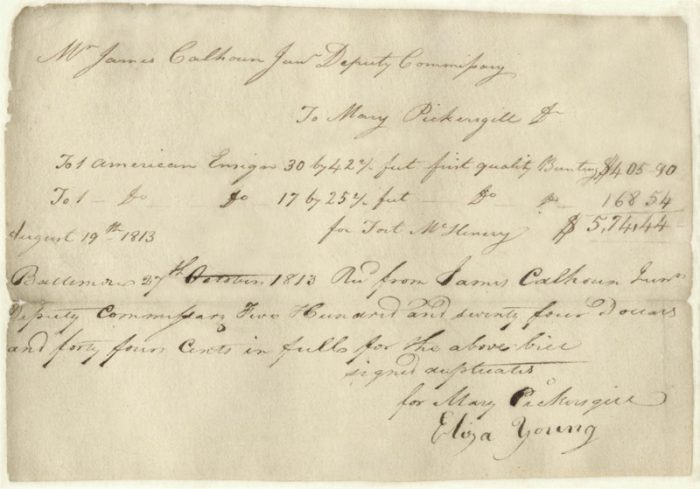

Pickersgill was paid $405.90 for the flag that became the Star-Spangled Banner, more than most Baltimoreans earned in a year. Courtesy of Flag House and Star-Spangled Banner Museum.

The first Flag Act, adopted on June 14, 1777, created the original United States flag of thirteen stars and thirteen stripes. The Star-Spangled Banner has fifteen stars and fifteen stripes as provided for in the second Flag Act approved by Congress on January 13, 1794. The additional stars and stripes represent Vermont (1791) and Kentucky (1792) joining the Union. (The third Flag Act, passed on April 4, 1818, reduced the number of stripes back to thirteen to honor the original thirteen colonies and provided for one star for each state — a new star to be added to the flag on the Fourth of July following the admission of each new state.) Pickersgill spent between six and eight weeks making the flags, and they were delivered to Fort McHenry on August 19, 1813. The government paid $405.90 for the garrison flag and $168.54 for the storm flag. The garrison flag would soon after be raised at Fort McHenry and ultimately find a permanent home at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. The whereabouts of the storm flag are not known.

The War of 1812 and the Burning of Washington

Although its events inspired one of our most famous national songs, the War of 1812 is itself a relatively little-known war in American history. Despite its complicated causes and inconclusive outcome, the conflict helped establish the credibility of the young United States among other nations. It also fostered a strong sense of national pride among the American people, and those patriotic feelings are reflected and preserved in the song we know today as our national anthem.

Action between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, August 19, 1812. Painting by Michel Felice Corne.

Britain’s defeat at the 1781 Battle of Yorktown marked the conclusion of the American Revolution and the beginning of new challenges for a new nation. Not even three decades after the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which formalized Britain’s recognition of the United States of America, the two countries were again in conflict. Resentment for Britain’s interference with American international trade and impressment of American sailors combined with American expansionist visions led Congress to declare war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812.

In the early stages of the war, the American navy scored victories in the Atlantic and on Lake Erie while Britain concentrated its military efforts on its ongoing war with France. But with the defeat of Emperor Napoleon’s armies in April 1814, Britain turned its full attention to the war against an ill-prepared United States. Admiral Alexander Cochrane, the British naval commander, prepared to attack U.S. coastal areas, and General Robert Ross sought to capture towns along the East Coast to create diversions while British army forces attacked along the northern boundaries of the United States.

“Capture of the City of Washington”, Based on an engraving from Rapin’s History of England, published by J. & J. Gundee, Albion Press, London, 1815.

In August 1814, General Ross and his seasoned troops landed near the nation’s capital. On August 24, at Bladensburg, Maryland, about 30 miles from Washington, his five-thousand-member British force defeated an American army twice its size. That same night, British troops entered Washington. They set fire to the United States Capitol, the President’s Mansion, and other public buildings. The local militia fled, and President James Madison and wife Dolley barely escaped.

The Battle of Baltimore

With Washington in ruins, the British next set their sights on Baltimore, then America’s third-largest city. Moving up the Chesapeake Bay to the mouth of the Patapsco River, they plotted a joint attack on Baltimore by land and water. On the morning of September 12, General Ross’s troops landed at North Point, Maryland, and progressed towards the city. They soon encountered the American forward line, part of an extensive network of defenses established around Baltimore in anticipation of the British assault. During the skirmish with American troops, General Ross, so successful in the attack on Washington, was killed by a sharpshooter. Surprised by the strength of the American defenses, British forces camped on the battlefield and waited for nightfall on September 13, planning to attempt another attack under cover of darkness.

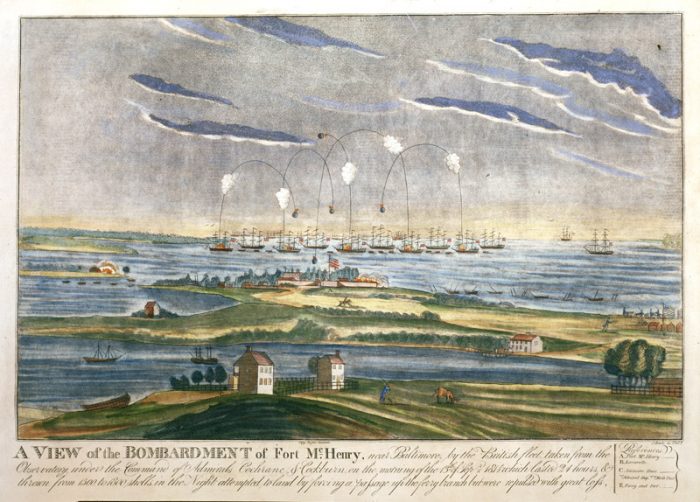

Print by J. Bower, Philadelphia, 1816. One of the soldiers who was in the fort during the 25-hour bombardment wrote, “We were like pigeons tied by the legs to be shot at.”

Meanwhile, Britain’s naval force, buoyed by its earlier successful attack on Alexandria, Virginia, was poised to strike Fort McHenry and enter Baltimore Harbor. At 6:30 AM on September 13, 1814, Admiral Cochrane’s ships began a 25-hour bombardment of the fort. Rockets whistled through the air and burst into flame wherever they struck. Mortars fired 10- and 13-inch bombshells that exploded overhead in showers of fiery shrapnel. Major Armistead, commander of Fort McHenry and its defending force of one thousand troops, ordered his men to return fire, but their guns couldn’t reach the enemy’s ships. When British ships advanced on the afternoon of the 13th, however, American gunners badly damaged them, forcing them to pull back out of range. All through the night, Armistead’s men continued to hold the fort, refusing to surrender. That night British attempts at a diversionary attack also failed, and by dawn they had given up hope of taking the city. At 7:30 on the morning of September 14, Admiral Cochrane called an end to the bombardment, and the British fleet withdrew. The successful defense of Baltimore marked a turning point in the War of 1812. Three months later, on December 24, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent formally ended the war.

Because the British attack had coincided with a heavy rainstorm, Fort McHenry had flown its smaller storm flag throughout the battle. But at dawn, as the British began to retreat, Major Armistead ordered his men to lower the storm flag and replace it with the great garrison flag. As they raised the flag, the troops fired their guns and played “Yankee Doodle” in celebration of their victory. Waving proudly over the fort, the banner could be seen for miles around—as far away as a ship anchored eight miles down the river, where an American lawyer named Francis Scott Key had spent an anxious night watching and hoping for a sign that the city—and the nation—might be saved.

The inspiration of Frances Scott Key: From poem to anthem

Before departing from a ravaged Washington, British soldiers had arrested Dr. William Beanes of Upper Marlboro, Maryland, on the charge that he was responsible for the arrests of British stragglers and deserters during the campaign to attack the nation’s capital. They subsequently imprisoned him on a British warship.

Friends of Dr. Beanes asked Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key to join John S. Skinner, the U.S. government’s agent for dealing with British forces in the Chesapeake, and help secure the release of the civilian prisoner. They were successful; however, the British feared that Key and Skinner would divulge their plans for attacking Baltimore, and so they detained the two men aboard a truce ship for the duration of the battle. Key thus became an eyewitness to the bombardment of Fort McHenry.

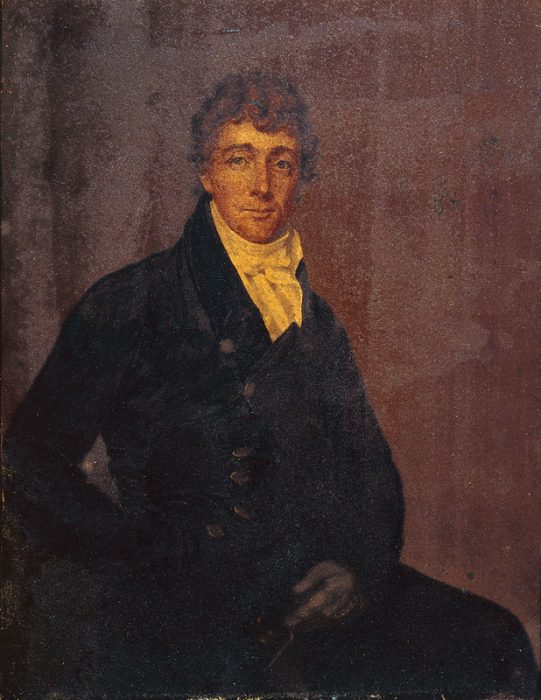

Portrait of Francis Scott Key, attributed to Joseph Wood, about 1825. Courtesy Walters Art Gallery.

When he saw “by the dawn’s early light” of September 14, 1814, that the American flag soared above the fort, Key knew that Fort McHenry had not surrendered. Moved by the sight, he began to compose a poem on the back of a letter he was carrying. On September 16, Key and his companions were taken back to Baltimore and released. Key took a room in the Indian Queen Hotel and spent the night revising and copying out the four verses he had written about America’s victory. The next day he showed the poem to his wife’s brother-in-law, Judge Joseph Nicholson, who had commanded a volunteer company at Fort McHenry. Nicholson responded enthusiastically and urged Key to have the poem printed. First titled “The Defence of Fort McHenry,” the published broadside included instructions that it be sung to the 18th-century British melody “Anacreon in Heaven” — a tune Key had in mind when he penned his poem. Copies of the song were distributed to every man at the fort and around Baltimore. The first documented public performance of the words and music together took place at the Holliday Street Theatre in Baltimore on October 19, 1814. A music store subsequently published the words and music under the title “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

During the 19th century, “The Star-Spangled Banner” became one of the nation’s best-loved patriotic songs. It gained special significance during the Civil War, a time when many Americans turned to music to express their feelings for the flag and the ideals and values it represented. By the 1890s, the military had adopted the song for ceremonial purposes, requiring it to be played at the raising and lowering of the colors. In 1917, both the army and the navy designated the song the “national anthem” for ceremonial purposes. Meanwhile, patriotic organizations had launched a campaign to have Congress recognize “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the U.S. national anthem. After several decades of attempts, a bill making “The Star-Spangled Banner” our official national anthem was finally passed by Congress and signed into law by President Herbert Hoover on March 3, 1931.

The Star-Spangled Banner and the Smithsonian

Sometime before his death in 1818, Lieutenant Colonel George Armistead acquired the flag that was immortalized in Key’s poem as the “Star-Spangled Banner.” While there exists no documented evidence as to how Armistead came to possess the flag, it is generally understood that he simply kept it as a memento of the triumphant battle.

At the death of Armistead’s widow in 1861, the Star-Spangled Banner was bequeathed to his daughter, Georgiana Armistead Appleton, who recognized that it held national as well as familial significance. As its owner, she permitted the flag to be publicly exhibited on several occasions. Eben Appleton, Armistead’s grandson, inherited the flag from his mother in 1878. Faced with the public’s increasing curiosity about the Star-Spangled Banner, he began to seek an appropriate repository. In 1907, Appleton lent the historic flag to the Smithsonian Institution, and in 1912 he offered the flag as a permanent gift to the nation. He later wrote, “It is always such a satisfaction to me to feel that the flag is just where it is, in possession for all time of the very best custodian, where it is beautifully displayed and can be conveniently seen by so many people.”

Souvenir snippings

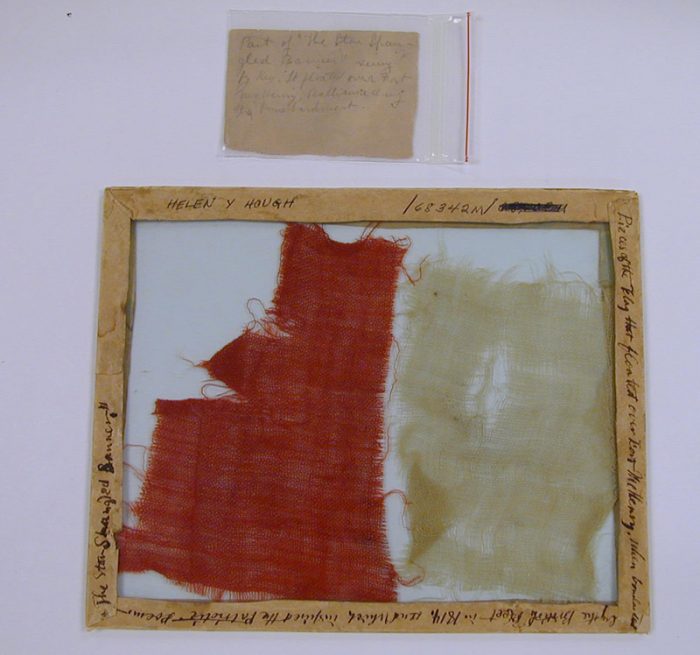

In the late 1800s, souvenirs, or relics, of important events and people in American history became highly prized and collectible objects. The Star-Spangled Banner, historic and celebrated, was subjected to this practice.

The Armistead family received frequent requests for pieces of their flag, but reserved the treasured fragments for veterans, government officials, and other honored citizens. As Georgiana Armistead Appleton noted, “had we given all that we have been importuned for little would be left to show.” Despite efforts to limit the practice, however, over two hundred square feet of the Star-Spangled Banner was eventually given away, including one of the stars.

The Armistead family gave away dozens of small pieces of the flag. “Indeed had we have given all we had been importuned for,” Georgiana Appleton wrote, “little would be left to show.”

By giving away snippings, the Armisteads could share the Star-Spangled Banner with others who loved the flag. The citizens who received these mementos treated them with reverence and pride. Some framed and displayed these pieces of history in their homes; others donated them to museums. Today, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History has thirteen Star-Spangled Banner fragments in its collections. Since conservators and curators cannot be sure from which part of the flag these fragments were taken, the pieces cannot be integrated back into the flag. However, they can be analyzed, allowing conservators to document changes in the condition of the flag’s fibers and better understand how time and exposure to light and dirt have affected the flag.

1914 conservation

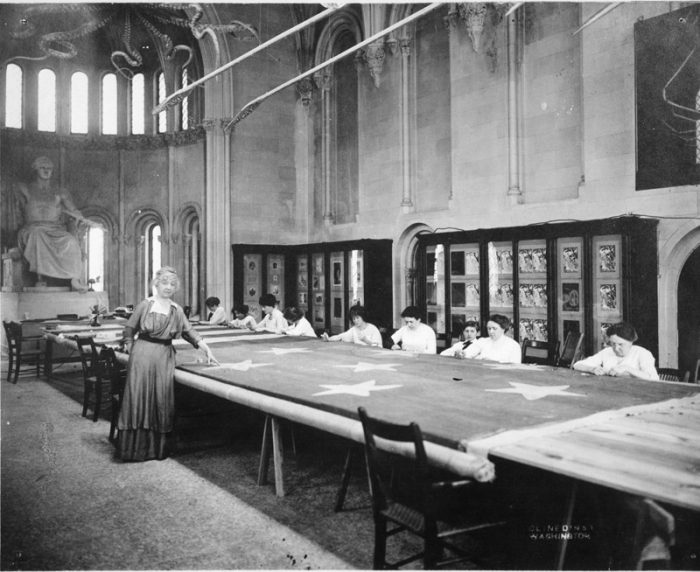

By the time it arrived at the Smithsonian in 1907, the Star-Spangled Banner was already in a fragile and tattered condition. In 1914, the Smithsonian hired Amelia Fowler, a well-known flag restorer and embroidery teacher, to “resuscitate” the flag. Working with a team of ten needlewomen, Fowler first removed a canvas backing that had been attached to the flag in 1873, when it was displayed and photographed for the first time at the Boston Navy Yard by Admiral George Preble. The women then attached the flag to a new linen backing, sewing approximately 1.7 million interlocking stitches to form a honeycomb-like mesh over the flag’s surface. Fowler’s work took eight weeks (mid-May to mid-July 1914), and she charged the Smithsonian $1243: $243 for materials, $500 for herself, and $500 to be divided among her ten needlewomen.

The public was so interested in the flag that Francis Scott Key had seen “by the dawn’s early light” that members of the press clamored for an opportunity to photograph it. Three days after it arrived in Washington, the flag was briefly displayed from the Smithsonian castle.

In 1914 the Smithsonian hired Amelia Fowler, a professional flag restorer, to preserve the flag. With a team of needlewomen, she sewed the flag to a linen backing using a uniform network of stitches.

The flag was then displayed in a glass case in the Smithsonian’s Arts and Industries Building. It remained on view there for nearly 50 years, except for two years during World War II, during which time it was housed in a government warehouse in Virginia, to be protected from possible bombing raids on the nation’s capital. In 1964 the flag was moved to the new National Museum of History and Technology (now the National Museum of American History), where it was displayed in the central hall on the second floor.

1998-2006 conservation

During the time that the Star-Spangled Banner was displayed in Flag Hall, museum staff recognized that inconsistent temperatures and humidity and high light levels had adversely affected the flag. In 1981, the Smithsonian began a two-year preservation effort: staff vacuumed the flag to reduce accumulated dust, installed new lighting and air-handling systems, and mounted a screen in front of the flag to protect it from light and damaging airborne matter.

When the new Museum of History and Technology (now NMAH) opened in 1964, the Star-Spangled Banner was featured in the central Flag Hall where it remained for over 30 years.

By 1994, museum officials recognized the need for further conservation, and in 1996 they began developing a plan to preserve the Star-Spangled Banner using modern, scientific conservation techniques. This most recent preservation effort was formally launched in 1998 with the flag’s inclusion in “Save America’s Treasures,” a wide-reaching Millennium preservation project initiated by First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. At this time, the flag was taken down from the wall where it had hung since 1964; in 1999, it was moved to the climate- and light-controlled conservation lab where it remains today.

It took conservators nearly two years to remove Fowler’s stitching and linen backing. Doing so allowed them to see the flag’s true condition and learn more about its construction. They examined the flag’s colors and fibers. They measured stains, holes, and mends, and removed those mends that stressed the fibers. The next step was to remove harmful materials from the flag. Using dry cosmetic sponges, conservators blotted the flag and lifted off much of the surface dirt; its composition offered insights into the flag’s history. After extensive research and analysis, conservators used an acetone/water solution to remove the most harmful contaminants.

In the final phase, to prepare the Star-Spangled Banner for reinstallation in a permanent exhibition gallery, conservators attached a lightweight polyester fabric called Stabiltex to one side. This provides enough support to hold the flag together and allow it to be displayed.

The conservation goal has not been to “restore” or “fix” the flag, but rather to prevent further deterioration.

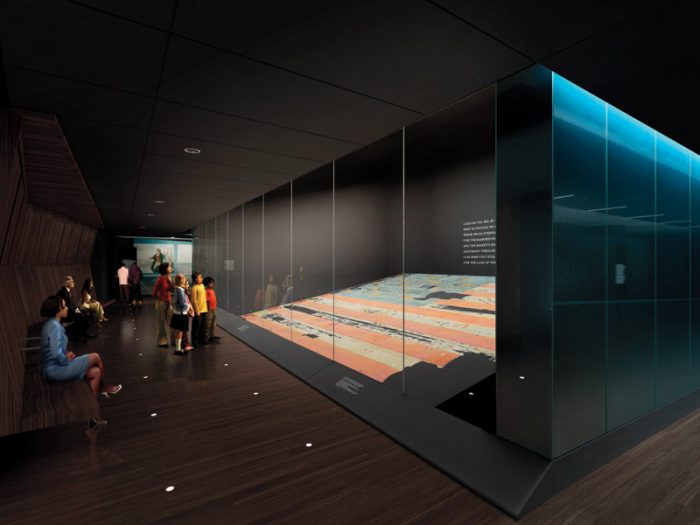

A new home

Conservators and curators collaborated with architects and engineers to develop a long-term preservation plan for the Star-Spangled Banner. This included constructing a state-of-the-art flag chamber with a climate-controlled environment and low light levels, and displaying the flag at a shallow angle. All of these features will help preserve the flag for future generations. The state-of-the-art gallery opened November 21, 2008.

Star-Spangled Banner Flickr page

Posted: 4 July 2023

-

Categories:

American History Museum , Feature Stories , History and Culture